Surely many, upon hearing the word “epilepsy,” will say that this is a mental illness and should be treated by a psychiatrist. This is fundamentally wrong. If you suspect epilepsy, you need to see a neurologist, since epileptology, the science that studies epilepsy, is a branch of neurology.

A child with epilepsy can be observed by a psychiatrist if he has mental disorders caused by epilepsy itself or concomitant pathologies. But epilepsy itself is treated by a neurologist.

3.2. Benign epilepsy of childhood with occipital paroxysms

general characteristics

Benign epilepsy of childhood with occipital paroxysms is one of the forms of idiopathic locally caused epilepsy of childhood, characterized by attacks that occur predominantly in the form of paroxysms of visual disturbances and often ending in migraine headache. The age of manifestation of the disease varies from 1 to 17 years.

Benign occipital epilepsy with an early onset occurs in children under 7 years of age and is characterized by rare, predominantly nocturnal paroxysms. The attack, as a rule, begins with vomiting, tonic deviation of the eyeballs to the side and impaired consciousness. In some cases, there is a transition to hemiconvulsions or a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. The duration of attacks varies from several minutes to several hours. These patients may experience the status of partial seizures [Early-onset..., 1997; Temin P.A., Nikanorova M.Yu., 1999].

Benign occipital epilepsy with late onset manifests itself in children 3–17 years old and is characterized by visual phenomena (transient visual impairment, amaurosis, elementary visual hallucinations (flickering of luminous objects, figures, flashes of light before the eyes), complex (scene-like) hallucinations) and “non-visual” symptoms (hemiclonic convulsions, generalized tonic-clonic convulsions, automatisms, dysphasia, dysesthesia, versive movements). Attacks predominantly occur during the daytime and occur, as a rule, with preserved consciousness. In the post-attack state, diffuse or migraine-like headache may occur, sometimes accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

Patients with this form of epilepsy are characterized by normal intelligence and neuropsychic development.

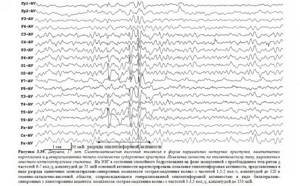

Electroencephalographic patterns

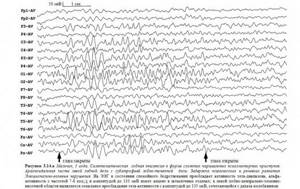

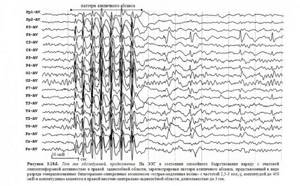

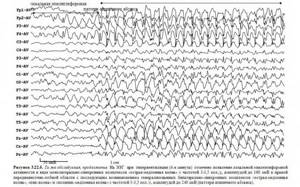

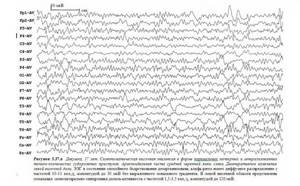

Interictal EEG is characterized by normal basic activity and the presence of high-amplitude mono- or bilateral spikes, sharp waves, sharp-slow wave complexes, including those with “rolandic” morphology, or slow waves in the occipital or posterior temporal regions. It is characteristic that pathological EEG patterns, as a rule, appear when the eyes are closed and disappear when the eyes are open [Zenkov L.R., 1996].

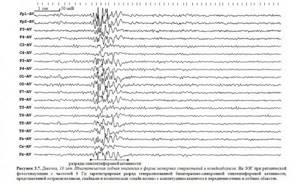

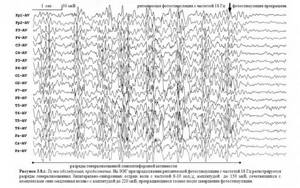

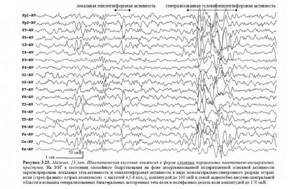

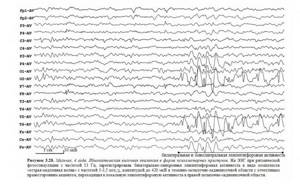

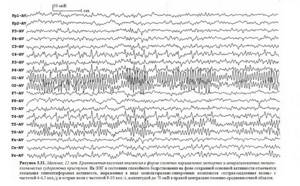

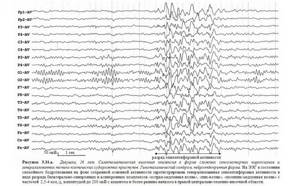

Occipital epileptiform activity can be combined with generalized bilateral spike-wave and polyspike-wave complexes. Sometimes epileptiform activity in this form of epilepsy can be represented by short generalized discharges of peak-wave complexes with a frequency of 3 counts/s, or is localized in the frontal, central-temporal, central-parietal-temporal leads (

). Also, interictal EEG may not show any changes [Mukhin K.Yu. et al., 2004; Atlas..., 2006].

Seizure EEG may be characterized by unilateral slow activity interspersed with spikes.

In occipital epilepsy with an early onset, the EEG during an attack is represented by high-amplitude sharp waves and slow “sharp-slow wave” complexes in one of the posterior leads, followed by a diffuse distribution.

In occipital epilepsy with a late onset, the EEG shows rhythmic fast activity in the occipital leads during an attack, followed by an increase in its amplitude and a decrease in frequency without post-attack slowing [Atlas..., 2006], and generalized slow “acute-slow wave” complexes may be observed.

What examination helps identify epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a chronic disease in which foci of excessive excitation appear in the brain. It can occur at any age. According to the World Health Organization, about 50,000,000 people worldwide suffer from epilepsy. The proportion of the population with active epilepsy (and therefore in need of treatment) in 2021 ranges from 4 to 10 per 1000 people.

The only method for reliably detecting epilepsy is an EEG - a recording of the electrical activity of the brain, which makes it possible to detect these foci.

Additional methods - MRI, computed tomography, genetic studies help to carry out differential diagnosis, for example, to identify the site of hemorrhage or tumor, the presence of hereditary pathology.

A typical EEG session lasts 20-30 minutes and quite often does not reveal any signs of disease in a child or adult, even if there were suspicious symptoms.

Therefore, if there is a suspicion of epilepsy, video EEG monitoring of sleep and a long period of wakefulness is carried out with functional tests (synonyms are video EEG monitoring of night sleep, video EEG monitoring of daytime sleep, video EEG monitoring of night sleep, video EEG monitoring of 24 hours, and so on), which allow you to provoke an attack. Parents are often worried when they hear that the doctor will try to cause an attack, however, sometimes this is the only way to make a completely reliable diagnosis.

Parents should be aware that most children whose EEG shows epileptiform activity do not have epilepsy . They are at risk, but often do not suffer a single attack in their entire lives and do not need any treatment. Moreover, 10% of people have experienced a convulsive episode at least once in their lives, but they are not diagnosed with epilepsy, since one of the main criteria for making such a diagnosis is the regularity of attacks.

Manifestations of epilepsy are not:

- Sleepwalking (sleepwalking). Sleepwalking in itself is not a manifestation of epilepsy. If any other symptoms are present, they must be considered together.

- Headache. Headache is a syndrome that can indicate the presence of a variety of diseases and must also be considered in conjunction with other symptoms.

- Hyperkinesis, tics. Hyperkinesis is a violent stereotypical movement; in children it can be a manifestation of a whole group of diseases and is not always an indication for an EEG.

- Bedwetting (enuresis). It occurs both in children with epilepsy and in those who do not suffer from it.

3.4. Epilepsy with seizures provoked by specific factors

general characteristics

Epilepsy with seizures provoked by specific factors is characterized by partial and partial-complex seizures, which are regularly reproduced by some direct influence. A large group consists of reflex attacks.

Haptogenic seizures are caused by thermal or tactile stimulation of a certain area of the body surface, usually projected into the zone of epileptogenic focus in the cortex when it has a destructive focal lesion.

Photogenic seizures are caused by flickering light and manifest as minor, myoclonic, and grand mal seizures.

Audiogenic seizures are caused by sudden sounds, certain melodies [Ictal..., 2003] and are manifested by temporal psychomotor, grand mal, myoclonic or tonic seizures.

Startle seizures are triggered by a sudden startling stimulus and manifest as myoclonic or brief tonic seizures.

Electroencephalographic patterns

Interictal EEG may be within normal limits, but is somewhat more likely to show the following changes.

During haptogenic seizures, during the interictal period, focal epileptiform patterns are recorded on the EEG in the parietotemporal region of the hemisphere (sometimes in both hemispheres) opposite the somatic zone. During an attack, the appearance or activation and generalization of primary focal epileptiform activity is noted.

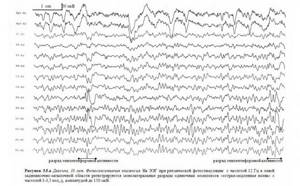

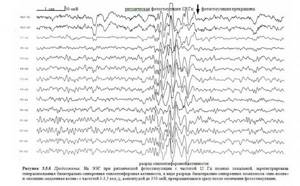

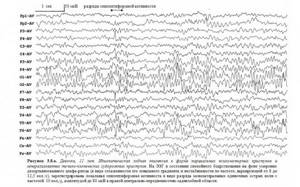

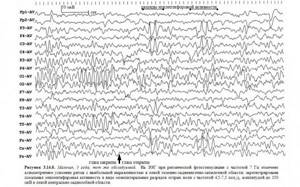

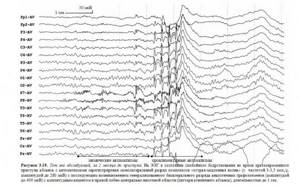

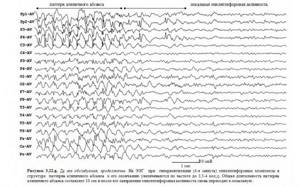

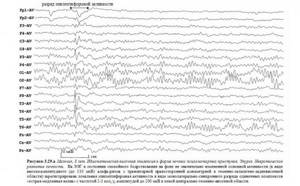

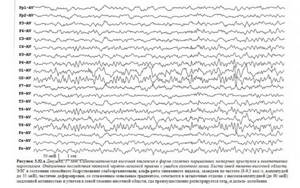

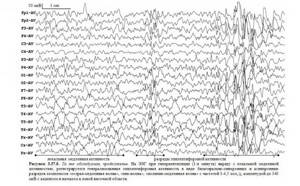

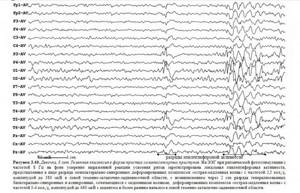

During photogenic seizures, in the interictal period and during an attack, focal slow waves and epileptiform patterns are recorded on the EEG in the occipital, parietal or temporal regions of one (

), sometimes both hemispheres and/or hypersynchronous generalized, usually bilaterally synchronous epileptiform activity (

).

During audiogenic seizures , in the interictal period and during an attack, the EEG reveals slow waves, epileptiform patterns in the temporal regions or diffusely in one, sometimes both hemispheres and/or hypersynchronous generalized, usually bilaterally synchronous epileptiform activity.

During startle attacks , in the interictal period and during the attack, the EEG records bilaterally synchronous flashes of theta waves, epileptiform patterns in the temporal, parietal areas or diffusely in one, sometimes both hemispheres and/or hypersynchronous generalized discharge, usually bilaterally synchronous epileptiform activity [ Zenkov L.R., 1996; 2001; Atlas..., 2006].

3.5. Frontal lobe epilepsy

general characteristics

Frontal epilepsy is a locally caused form of epilepsy in which the epileptic focus is localized in the frontal lobe.

The most characteristic signs of frontal epilepsy are: stereotyped attacks, their sudden onset (usually without an aura), high frequency of attacks with a tendency to be serial and short duration (30–60 sec.) Unusual motor phenomena are often expressed (pedaling with legs, chaotic movements, complex gestures automatisms), absence or minimal post-ictal confusion, frequent occurrence of attacks during sleep, their rapid secondary generalization, frequent occurrence of episodes of status elepticus in the anamnesis.

Depending on the location in the frontal lobe, R. Chauvel and J. Bancaud (1994) distinguish a number of types of frontal seizures.

Seizures of the anterior frontal lobe

Frontopolar attacks are manifested by a sudden disturbance of consciousness, freezing of the gaze, violent thinking and violent actions, tonic turning of the head and eyes, vegetative symptoms, possibly tonic tension of the body and falling.

Orbitofrontal attacks are manifested by olfactory hallucinations, visceral sensory symptoms, impaired consciousness, gestural automatisms, nutritional disorders, autonomic symptoms, and involuntary urination.

Seizures of the medial frontal lobe

Medial median seizures are manifested by frontal absences (characterized by impaired consciousness, speech cessation, interruption of motor activity, gestural automatisms, and sometimes tonic rotation of the head and eyes) and psychomotor paroxysms (characterized by impaired consciousness, tonic rotation of the head and eyes, gestural automatisms, tonic postural phenomena, involuntary urination, secondary generalization is possible).

Dorsolateral median attacks are manifested by impaired consciousness, violent thinking, complex visual illusions, tonic rotation of the head and eyes, tonic postural phenomena, secondary generalization, and sometimes characterized by autonomic symptoms.

Cingular attacks are manifested by an expression of fear on the face, impaired consciousness, vocalization, complex gestural automatisms, emotional symptoms, facial flushing, involuntary urination, and sometimes visual hallucinations.

Posterior frontal lobe seizures

Seizures emanating from the precentral zone of the motor cortex occur with preserved consciousness and are manifested by partial myoclonus (mainly in the distal limbs), simple partial motor seizures (in the form of a “Jacksonian march”, developing contralateral to the focus and spreading in an ascending manner (leg-arm-face) ) or downward (face-arm-leg) march), tonic postural paroxysms in combination with clonic twitching, unilateral clonic seizures.

Seizures emanating from the premotor zone of the motor cortex occur with preserved consciousness and are manifested by tonic postural paroxysms with predominant involvement of the upper extremities, tonic rotation of the head and eyes.

Seizures emanating from the supplementary motor area occur with intact (or partially impaired) consciousness and are often manifested by somatosensory aura, postural tonic postures (fencing pose) with predominant involvement of the proximal limbs, tonic rotation of the head and eyes, stopping speech or vocalization, pedaling movements of the legs , mydriasis.

Opercular attacks are manifested by taste hallucinations and illusions, fear, impaired consciousness, chewing and swallowing automatisms, clonic facial twitching, hypersalivation, hyperpnea, tachycardia, mydriasis.

Most researchers emphasize that a clear determination of the localization of the epileptogenic zone in the frontal lobe is not always possible. Therefore, it is more appropriate to differentiate seizures in frontal epilepsy into partial motor ones, manifested either by a contralateral versive component or unilateral focal clonic motor activity in combination (or without) with a tonic component in the late phases of the attack; partial psychomotor, debuting with sudden stupefaction and freezing of the gaze; seizures from the supplementary motor area, characterized by tonic posturing of the limbs.

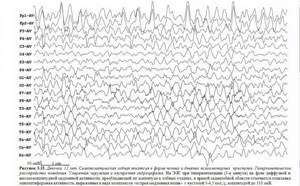

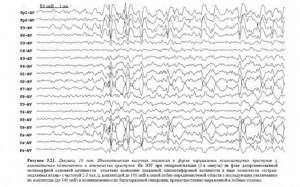

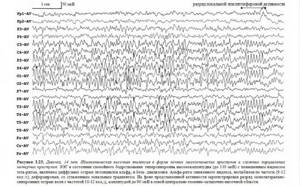

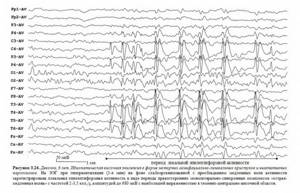

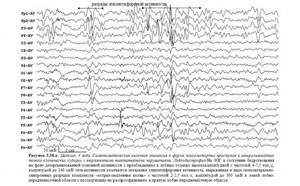

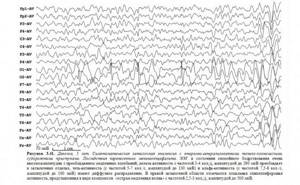

Electroencephalographic patterns

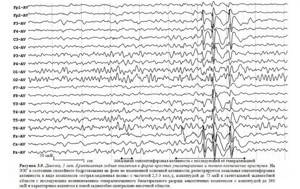

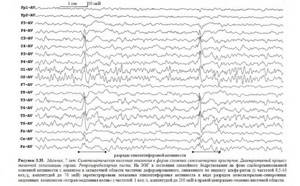

In the interictal period, the EEG may show disorganization and/or deformation of the main rhythms. Epileptic patterns are often absent. If epileptiform activity is recorded, it is represented by spikes, sharp waves, peak-wave or slow (usually theta range) activity in the frontal, fronto-central, fronto-temporal or fronto-central-temporal leads bilaterally in the form of independent foci or bilaterally synchronously with amplitude asymmetry. Characteristic is the occurrence of local epileptiform activity, accompanied by its bilateral spread and (or) generalization (in some cases in the form of an atypical absence pattern); the appearance of generalized bilateral epileptiform activity is possible, more often with its amplitude predominance in the frontal, frontotemporal regions (

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

).

Local disturbances (exaltation or significant reduction) of rhythms are also possible. When the supplementary motor area is damaged, pathological EEG patterns are often ipsilateral to clinical phenomena or bilateral.

Sometimes EEG changes in frontal epilepsy can precede the clinical appearance of seizures and manifest as bilateral high-amplitude single sharp waves immediately following periods of rhythm flattening; low-amplitude fast activity mixed with spikes; rhythmic spike waves or rhythmic slow waves of frontal localization [Petrukhin A.S., 2000].

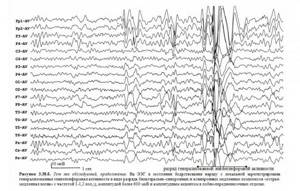

During an attack, the EEG may show local epileptiform activity with (or without) the subsequent appearance of generalized and (or) bilaterally synchronous discharges of peak-wave complexes, reflecting secondary generalization (

). High-amplitude regular theta and delta waves may occur, mainly in the frontal and (or) temporal leads [Zenkov L.R., 1996, 2001]. Also, during an attack, diffuse flattening may occur, most pronounced in the focal area, followed by the appearance of rapid activity, increasing in amplitude and decreasing in frequency [Atlas..., 2006].

What should parents pay attention to?

The first and most important thing is to remember that epilepsy is not always seizures with loss of consciousness. In epilepsy, seizures can be local (local): twitching of the arm, leg, corner of the mouth, or they may be completely absent. Seizures can be manifested by blinking, drooling, redness of the face, episodes of “switching off” that the child does not remember, changes in behavior (the appearance of aggression, fear).

Often the child's status may only be developmental delay.

Not every seizure can be a manifestation of epilepsy that requires serious treatment. Convulsive syndrome is the body’s response to intoxication, endocrine diseases, fever, cerebrovascular accidents, increased intracranial pressure and other numerous pathologies.

Parents should be alert to:

- Asymmetry. Only one arm or leg, one half of the face twitches, and one half of the torso is involved in the process.

- Stereotyping of attacks.

- Repeatability.

- Spread of twitching, transition from one part of the body to another.

If you have any suspicion, you should try to “catch” the attack on video. Place a video camera in your child's room and record his periods of wakefulness and sleep. If you find something suspicious, take the note with you to your doctor’s appointment. Sometimes a recording of an attack becomes the only and main evidence of a problem, however, the doctor will always consider the attack in conjunction with other symptoms: developmental delay, motor and neurological disorders, data from other examinations.

3.6. Temporal lobe epilepsy

general characteristics

Temporal lobe epilepsy is a locally caused, often symptomatic, form of epilepsy in which the epileptic focus is localized in the temporal lobe.

Temporal lobe epilepsy manifests itself as simple, complex partial and secondary generalized seizures or a combination thereof.

The most typical signs of temporal lobe epilepsy are: the predominance of psychomotor seizures, a high frequency of isolated auras, oroalimentary and carpal automatisms, frequent secondary generalization of seizures [Troitskaya L.A., 2006].

Complex partial (psychomotor) seizures can begin with or without a preceding aura and are characterized by loss of consciousness with amnesia, lack of response to external stimuli, and the presence of automatisms.

Auras include epigastric (tickling, epigastric discomfort), mental (fear), olfactory, vegetative (pallor, redness of the face), intellectual (feeling of something already seen, already heard, derealization), auditory (auditory illusions and hallucinations (unpleasant sounds, voices, difficult-to-describe auditory sensations)) and visual (illusions and hallucinations in the form of micro- and macropsia, flashes of light, the sensation of an object being removed) aura.

Automatisms are divided into oroalimentary (smacking, chewing, licking lips, swallowing); facial expressions (various grimaces, facial expressions of fear, surprise, smiling, laughter, frowning, forced blinking), gestural (patting one's hands, rubbing one's hand on one's hand, stroking or scratching one's body, sorting through clothes, shaking off, shifting objects, and looking around , marking in place, rotating around its axis, standing up; it was revealed that automatisms in the hand are associated with damage to the ipsilateral temporal lobe, and dystonic positioning of the hand is associated with the contralateral one); outpatient (trying to sit down, stand up, walking, seemingly purposeful actions); verbal (speech disorders: slurred muttering, pronouncing individual words, sounds, sobbing, hissing; it was revealed that seizure speech is associated with damage to the dominant hemisphere, and aphasia and dysarthria - to the subdominant).

It has been noted that in children under 5 years of age, as a rule, there is no clearly identifiable aura, oroalimentary automatisms predominate and motor activity is most pronounced at the time of the attack.

The duration of psychomotor temporal paroxysms varies from 30 s to 2 min. After an attack, confusion, disorientation, and amnesia are usually observed [Atlas..., 2006]. Seizures occur both while awake and during sleep.

More often, in patients with psychomotor temporal paroxysms, clinical symptoms occur in a certain sequence: aura, then interruption of motor activity (maybe with a stoppage of gaze), then oroalimentary automatisms, repeated carpal automatisms (less often other automatisms), the patient looks around, then movements of the whole body .

Simple partial seizures often precede the onset of complex partial and secondary generalized seizures.

Simple partial motor seizures are manifested by local tonic or clonic-tonic convulsions, contralateral to the focus; postural dystonic paroxysms (in the contralateral hand, foot); versive and phonatory (sensory aphasia) seizures.

Simple partial sensory seizures are manifested by olfactory, gustatory, auditory, complex visual hallucinations and stereotypical non-systemic dizziness.

Simple partial vegetative-visceral attacks are manifested by epigastric, cardiac, respiratory, sexual and cephalgic paroxysms.

Simple partial seizures with impaired mental functions are manifested by dreamlike states, phenomena of derealization and depersonalization, affective and ideational (“failure of thoughts,” “whirlwind of ideas”) paroxysms [Temporal…, 1992, 1993; Petrukhin A.S., 2000].

With temporal lobe epilepsy, there are also so-called “temporal syncopes”, starting with an aura (usually dizziness) or without it and characterized by a slow shutdown of consciousness followed by a slow fall. During such attacks, oroalimentary or gestural automatisms may be noted; slight tonic tension of the muscles of the limbs, facial muscles [Late-onset..., 1994].

Epileptic activity from the temporal lobe often spreads to other areas of the brain. Clinical signs indicating the spread of epileptic activity to other parts are versive movements of the head and eyes, clonic twitching of the face and limbs (with the spread of epileptic activity to the anterior parts of the frontal lobe and premotor zone), secondary generalization with the manifestation of generalized tonic-clonic seizures (with involving both hemispheres of the brain in the process).

Neurological status is determined by the etiology of temporal lobe epilepsy.

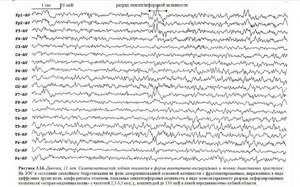

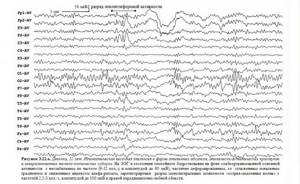

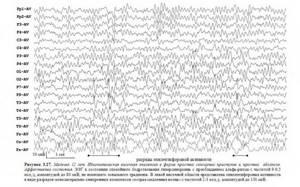

Electroencephalographic patterns

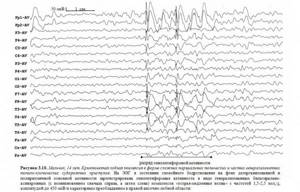

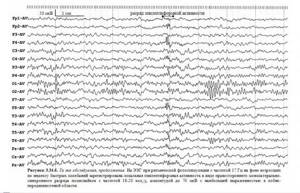

Interictal EEG may not show pathological patterns. Spike, sharp waves, peak-wave, polypeak-wave activity or bursts of theta waves can be recorded in the temporal, frontotemporal, central-parietal-temporal and/or parieto-occipital-temporal leads regionally or bilaterally (bilaterally synchronous with one-sided accent or independently); regional temporal slowing of electrical activity; general slowdown in core activity. Generalized peak-wave activity with a frequency of 2.5–3 Hz may be observed [Kaplov V.A., Ovnatanov B.S., 1987]; generalized epileptiform activity with emphasis and/or spread from the temporal region. An atypical absence pattern is a common finding. Sometimes pathological changes have a frontal focus (

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

).

Seizure EEG is characterized by local low-amplitude beta activity or slowing (first in the theta and then in the delta range) of electrical activity bitemporally or locally in the temporal leads. Then the pathological activity may spread beyond the temporal region [TassiL.et.al., 2001].

Within 10–40 s from the onset of clinical manifestations of an attack, a lateralized appearance of rhythmic theta or alpha activity (with a frequency of 5 counts/s or more) is possible [Ictal..., 1989; Walczak TS et. al., 1992]. Seizure EEG can also be represented by epileptiform activity in the temporal region [Petrukhin A.S., 2000]. In the post-attack period, slow activity on the side of the lesion is often detected.

3.7. Epilepsy of the parietal lobe

general characteristics

Parietal epilepsy is a locally caused form of epilepsy, characterized mainly by simple partial and secondary generalized paroxysms.

Parietal epilepsy usually debuts with somatosensory paroxysms, which are not accompanied by impaired consciousness, have a short duration (from a few seconds to 1–2 minutes) and, as a rule, are caused by the involvement of the postcentral gyrus in the epileptic process.

Clinical manifestations of somatosensory paroxysms include: elementary paresthesia, pain, disturbances in temperature perception (burning or cold sensation), “sexual attacks,” ideomotor apraxia, disturbances in the body diagram.

Elementary paresthesias are represented by numbness, tingling, tickling, a sensation of “crawling goosebumps”, “pin pricks” in the face, upper limbs and other segments of the body. Paresthesia can spread like a Jacksonian march and be combined with clonic twitching.

Painful sensations are expressed in the form of a sudden sharp, spasmodic, throbbing pain that is localized in one limb, or in part of a limb, sometimes it can spread like a Jacksonian march.

“Sexual attacks” are represented by unpleasant one-sided sensations of numbness, tingling, and sometimes pain in the genital area and mammary glands. These seizures are caused by epileptic activity in the paracentral lobule.

Ideomotor apraxia is represented by sensations of the impossibility of movement in a limb; in some cases, a Jacksonian march type distribution is noted in combination with focal tonic-clonic convulsions in the same part of the body.

Body schema disturbances include sensations of movement in a stationary limb or body part; feeling of flight, soaring in the air; a feeling of a body part being removed or shortened; feeling of enlargement or reduction of a part of the body; the feeling of the absence of a limb or the presence of an additional limb [Zenkov L.R., 1996].

Parietal seizures tend to spread epileptic activity to other areas of the brain, and therefore, in addition to somatosensory disturbances at the time of the attack, clonic jerking of the limb (frontal lobe), amaurosis (occipital lobe), tonic tension of the limb and automatisms (temporal lobe) can be observed. .

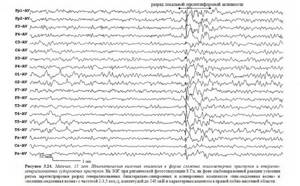

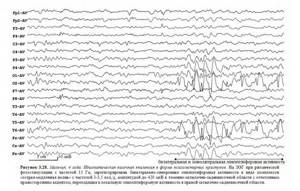

Electroencephalographic patterns

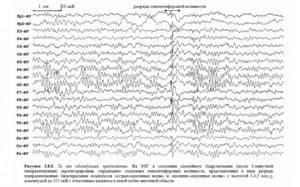

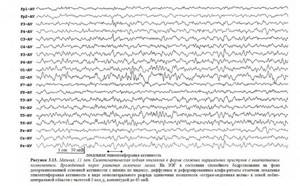

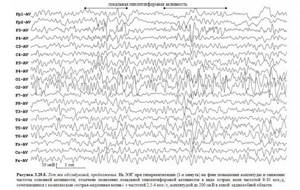

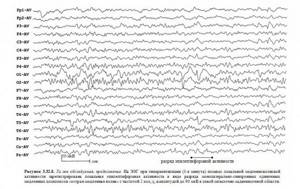

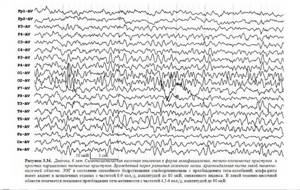

Interictal EEG often does not show pathological patterns [Parietal..., 1995]. If pathological activity is noted, it is represented by spikes, sharp waves, sometimes acute-slow wave and spike-wave complexes in the parietal leads, according to the nature of the attack [Zenkov L.R., 2001]. Often epileptiform activity is distributed outside the parietal region and can be represented in the temporal lobe of the same name [Parietal..., 1993] (

).

In the seizure EEG, spikes and “spike-wave” complexes can be recorded in the central-parietal and temporal regions, discharges of epileptiform activity can be bilateral (synchronous or in the form of a “mirror focus”) [Temin P.A., Nikanorova M.Yu., 1999].

3.8. Epilepsy of the occipital lobe

general characteristics

Occipital epilepsy is a locally caused form of epilepsy, characterized predominantly by simple partial paroxysms not accompanied by impaired consciousness.

Early clinical symptoms of occipital epilepsies are caused by epileptic activity in the occipital lobe, and late ones are caused by the spread of epileptic activity to other areas of the brain.

The initial clinical symptoms of occipital paroxysms include: simple visual hallucinations, paroxysmal amaurosis and visual field disturbances, subjective sensations in the area of the eyeballs, blinking, deviation of the head and eyes to the side contralateral to the epileptic focus.

Simple visual hallucinations are represented by bright flashes of light before the eyes, glowing spots, circles, stars, squares, straight or zigzag lines, which can be single or multi-colored, stationary or moving in the field of vision.

Paroxysmal amaurosis manifests itself in the form of blurred or temporary loss of vision, feeling like “blackness before the eyes” or “a white veil before the eyes.”

Paroxysmal visual field disturbances manifest as paroxysmal hemianopsia or quadrant hemianopia within seconds or minutes.

Subjective sensations in the area of the eyeballs are expressed primarily by a feeling of eye movement in the absence of objective symptoms.

Blinking is observed at the very beginning of the attack, is of a violent nature and resembles the fluttering of a butterfly's wings.

Electroencephalographic patterns

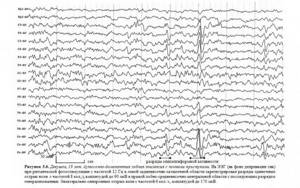

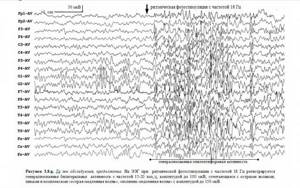

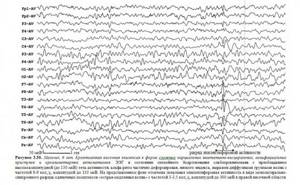

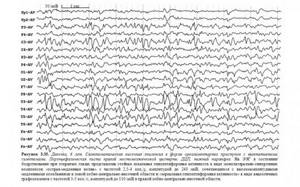

Interictal EEG may not show pathological patterns or may be represented by epileptiform activity in the occipital or posterior temporal region, sometimes bilaterally. The main activity may not be changed or there may be disorganization and slowness. Epileptiform activity can often also be falsely represented in the temporal lobe of the same name (

)

During an attack, epileptiform activity may spread with the appearance of “mirror” discharges.

Prognosis for epilepsy.

Epilepsy is always assessed by a doctor as a complex of symptoms.

Benign forms of epilepsy often require only observation and may resolve on their own with age.

In other cases, epilepsy and associated pathologies may require serious treatment, and the prognosis will depend on the severity of the underlying disease. Some of these pathologies can be cured completely, for example, by removing a tumor or eliminating the consequences of an injury. Then the attacks will disappear. In other cases, lifelong medication and work with a psychologist are required.