Pulmonologists at the Integramed clinic have extensive experience in diagnosing and treating interstitial lung diseases (ILD). Our clinic has in its arsenal all possible pulmonary examinations. We cooperate with the best specialists and medical institutions in Russia and the world. Here are some reasons to contact us:

- diagnostics are carried out using modern equipment

- pulmonologists from our medical center and colleagues from the Pulmonology Research Institute are a guarantee of quality

- diagnostics in 1-2 days

- selection of therapy and monitoring in accordance with international and Russian standards.

What are interstitial lung diseases?

This is a group of lung diseases in which the pulmonary interstitium (the framework of the lungs) undergoes changes. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) causes fibrosis (hardening) of the lungs, which interferes with the transport of oxygen from the air into the blood. The consequence of this is shortness of breath, both during physical activity and at rest.

ILD is a heterogeneous group of diseases. These include idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, sarcoidosis, exogenous allergic alveolitis, histiocytosis X (Langerhans cell histiocytosis), lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, pulmonary vasculitis, ILD due to systemic connective tissue diseases, occupational ILD and ILD associated with certain medications. Despite the fact that these diseases have similar clinical and radiological manifestations, they differ significantly in course, therapy and prognosis.

ILD is a disease with an unknown cause, however, the factors that in most cases contribute to the development of ILD are known. These include:

- inhalation for a long time of various toxic or irritating fumes, gases and dust (tobacco smoke, chemicals, flour, asbestos, quartz, metal, coal dust, etc.)

- some lung infections (viral, fungal)

- systemic connective tissue diseases (collagenosis)

- contact with bird allergens (pigeons, parrots)

- long-term use of certain medications

- exposure to radiation.

Symptoms

Signs of the underlying disease causing pneumosclerosis:

- chronic pneumonia

- Chronical bronchitis

- bronchiectasis

Dyspnea with diffuse pneumosclerosis, which at the beginning of the disease is observed only during exertion, but then appears when the person is at rest. A productive cough is characterized by the production of mucopurulent sputum. Severe diffuse cyanosis is typical.

Auscultatory and percussion signs:

- shortening of percussion sound

- limited mobility of the pulmonary edge

- fine wheezing

- weakened vesicular breathing with a hard tint

- dry scattered wheezing

Along with the symptoms of pneumosclerosis, the clinic of emphysema and chronic bronchitis often appears. Diffuse forms of pneumosclerosis are accompanied by precapillary hypertension of the pulmonary circulation and manifestations of cor pulmonale.

The following symptoms indicate lung cirrhosis::

- partial atrophy of the pectoral muscles

- severe deformation of the chest

- tracheal displacement

- shrinkage of intercostal spaces

- displacement of large vessels and heart to the affected side

- sudden decrease in breathing

- dull sound when percussing

- dry and moist rales detected by auscultation

With a limited form of pneumosclerosis, the patient does not complain of anything. Only a slight cough with minimal phlegm may bother you. When examining the affected side, it is discovered that the thorax in this place has a kind of depression.

Pneumosclerosis of diffuse origin has a symptom such as shortness of breath. At later stages it is present, even if the person is not taking any action at the moment (sitting or lying). The alveolar tissue is poorly ventilated, which is why the skin has a bluish tint. The Hippocrates finger sign is recorded, which indicates increasing respiratory failure. The patient complains of cough. At first it appears rarely, but then it becomes intrusive, purulent sputum is released. The course of pneumosclerosis aggravates the underlying disease.

In some cases, aching pain in the thoracic area is noted, patients may lose weight, look weakened, and causeless fatigue is likely. Symptoms of pulmonary cirrhosis may develop:

- atrophy of intercostal muscles

- gross deformity of the thorax

- displacement of the throat, large vessels and heart to the affected side

With diffuse pneumosclerosis, the cause of which is a violation of the hemodynamics of the small bloodstream, clinical symptoms of cor pulmonale sometimes appear. The severity of any form of pneumosclerosis correlates with the size of the affected areas.

Stages of the disease:

- compensated

- subcompensated

- decompensated

Emphysema and pneumosclerosis

A sign of pulmonary emphysema is the accumulation of increased amounts of air in the lung tissues. Pneumosclerosis, which is the result of chronic pneumonia, has very similar symptoms. The development of emphysema and pneumosclerosis is affected by infection of the bronchial wall, the influence of inflammation of the branches of the windpipe, and obstructions to the patency of the bronchi. Sputum accumulates in the small bronchi. Ventilation in this area of the lung can cause emphysema or pneumosclerosis. Diseases that are accompanied by bronchospasm, for example, bronchial asthma, can accelerate the development of these diseases.

Hilar pneumosclerosis

Connective tissue can grow in the hilar regions of the lung, then hilar pneumosclerosis is diagnosed. It is preceded by processes of inflammation or dystrophy, when the elasticity of the affected area is lost and gas exchange disturbances occur in it.

Local pneumosclerosis

Local pneumosclerosis, as already indicated, can be called limited by some authors. Symptomatically, it can be hidden for a long period, but upon auscultation, hard breathing and fine rales can be heard. It is detected by x-ray methods. The image shows an area of compacted lung tissue. Local pneumosclerosis may not cause pulmonary failure.

Focal pneumosclerosis

Focal pneumosclerosis can be a consequence of the destruction of the lung parenchyma, and the cause of the latter, in turn, is a lung abscess or cavities. The proliferation of connective tissue can be observed both at the site of existing and at the site of healed cavities and lesions.

Apical pneumosclerosis

In the apex of the lung in the apical form of the disease there is a lesion. As is typical for pneumosclerosis, the lung tissue at the apex is replaced by connective tissue. At first, the process is similar to bronchitis, and most often bronchitis precedes and becomes the cause of apical pneumosclerosis. It can be detected by x-ray.

Age-related pneumosclerosis

Age-related pneumosclerosis becomes the result of changes associated with the aging process of the human body. This form, as the name implies, develops only in elderly people if they have congestive phenomena due to pulmonary hypertension. The disease mainly affects men; smokers are at increased risk. If an x-ray reveals pneumosclerosis in an 80-year-old (or older) person, but the patient has no complaints, this is the norm.

Reticular pneumosclerosis

As the amount of connective reticular tissue increases, the lungs become less clean and clear, and the tissue acquires a mesh-like structure resembling a spider's web. For this reason, the normal pattern is almost not visible; it looks weakened. CT scan clearly shows compaction of connective tissue.

Basal pneumosclerosis

When connective tissue begins to grow in the basal parts of the lung, then pneumosclerosis is classified as basal. It is often preceded by lower lobe pneumonia. The radiograph shows increased clarity of the lung tissue in the basal regions, enhancing the pattern.

Moderate pneumosclerosis

At the onset of the disease, the proliferation of connective tissue replacing the pulmonary tissue is moderate. Changed lung tissue alternates with healthy parenchyma. An x-ray reveals this picture, but the patient has no complaints, nothing bothers him.

Postpneumonic pneumosclerosis

This form of the disease is a complication of pneumonia. The inflamed area looks like raw meat. Macroscopically, the affected area is more compacted; this area of the lung is smaller in size than normal.

Interstitial pneumosclerosis

In this form, the connective tissue mainly covers the interalveolar septa, tissues, surrounding vessels and bronchi. Interstitial pneumosclerosis is a consequence of interstitial pneumonia.

Peribronchial pneumosclerosis

Connective tissue grows, surrounding the bronchi. The cause of this form of pneumosclerosis is the transfer of bronchitis in a chronic form. For a long period of time, the patient does not feel any changes in the body; he may only be slightly bothered by a cough. Over time, sputum appears.

Post-tuberculosis pneumosclerosis

In post-tuberculosis pneumosclerosis, the proliferation of connective tissue occurs after recovery from pulmonary tuberculosis. This condition can develop into “post-tuberculosis disease,” in which there may be different nosological forms of nonspecific diseases, for example, COLD.

What are the symptoms of interstitial lung disease?

The main and most common manifestation of ILD is shortness of breath during physical activity, which, as a rule, gradually increases. In many cases, symptoms of ILD occur after an acute respiratory infection with long-lasting cough and fever; later shortness of breath occurs when walking.

Sometimes ILDs do not manifest themselves for several months or even years and are discovered by chance during a routine examination (fluorography, chest x-ray). Much less often, ILD begins acutely with a sharp increase in temperature, a persistent dry or unproductive cough, and difficulty breathing.

In addition to shortness of breath and cough, some types of ILD may be accompanied by extrapulmonary manifestations: joint pain, skin rashes, liver enlargement, visual disturbances, cardiac arrhythmias, etc.

How are interstitial lung diseases diagnosed?

In most cases, the first suspicion of ILD arises after fluorography or chest x-ray. However, these studies are not sensitive enough to determine the specific type of ILD, which is why there are often cases when such patients are treated for pneumonia for a long time and without results. Sometimes a patient with ILD may have a completely normal chest x-ray. In this regard, the diagnosis of ILD necessarily requires a computed tomography scan of the lungs. This study allows us to describe in detail the nature of changes in lung tissue.

The second necessary component of the diagnosis of ILD is a study of pulmonary function, and in this situation we are not talking about spirometry - a study of the function of external respiration, which is performed today in almost any clinic and hospital, but about a more detailed study of lung function with measurement of lung volumes and diffusion capacity, that is, the ability of the lungs to conduct oxygen from inhaled air into the blood.

Sometimes - in the presence of classic changes on a computed tomography of the lungs - these studies are enough to make a final diagnosis, but, unfortunately, such cases are rare. In other situations, a third stage of diagnosis is required - surgical biopsy of lung tissue, video thoracoscopy. This procedure is a surgical procedure that is performed in specialized thoracic surgery units.

The resulting biopsies (pieces) of lung tissue are examined under a microscope, and based on the nature of changes in the structure of the lung tissue, a final diagnosis is made, indicating the specific type of ILD. There is another method of obtaining a lung biopsy - with bronchoscopy. Of course, this is a more gentle and easier procedure to perform, which does not require hospitalization and is easier to tolerate by the patient himself, however, the amount of information obtained as a result is disproportionately less than with a surgical biopsy. Often, a bronchoscopic biopsy does not allow one to judge the diagnosis, and the doctor and the patient still return to the need for a surgical biopsy.

Thus, the diagnosis of ILD should always be carried out as accurately as possible in the interests of the patient himself. Sometimes the doctor may need additional studies, for example, immunological blood tests to clarify the role of molds or poultry allergens in the development of the disease, to diagnose systemic connective tissue diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic scleroderma, etc.) as a background for the occurrence of ILD, for analysis of blood gas composition in severe cases of the disease, etc.

Computed tomography of the lungs and a complete study of pulmonary function are used not only for the initial diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases, but also subsequently to monitor the course of the disease and evaluate the effectiveness of treatment.

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis is a rare disease that occurs mainly in childhood. The article presents literature data and describes a clinical case of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis in a 14-year-old child.

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis is a rare disease that occurs primarily in children. The article presents the published data and described a clinical case of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis in a child of 14 years.

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (brown induration of the lungs, Delen-Gellerstedt syndrome, “iron lung”) is a rare disease that is characterized by hemorrhage in the lungs and a wavy, relapsing course.

Studying the epidemiology of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis is complicated by the extreme rarity of this disease. Its frequency ranges from 0.24 to 1.23 per 1,000,000 population [2, 9, 10].

There are several assumptions regarding the etiology and pathogenesis of this disease. Opinions have been expressed regarding congenital structural disorders, increased permeability of the vascular wall of the pulmonary capillaries, the presence of abnormal anastomoses between the pulmonary arteries and veins [2], and a hereditary predisposition cannot be excluded [2, 4]. The immunopathological nature of the disease is supported by the presence of such a form as Heiner's syndrome - idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis with increased sensitivity to cow's milk [1, 7, 8], as well as the response to therapy with glucocorticosteroids and immunosuppressants [3]. The clinical picture of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis during exacerbation is characterized by cough, hemoptysis, body temperature rises, shortness of breath, cyanosis, and moist rales are heard in the lungs [1-3]. Hematological disorders are manifested by iron deficiency anemia with a hemolytic component, which is caused by hemolysis of red blood cells released from damaged capillaries [5]. Diagnostically significant is the detection of siderophages in sputum or tracheal aspirate, as well as in some cases in gastric lavage waters [1, 6]. A study of external respiration function reveals predominantly restrictive ventilation disorders. The X-ray picture varies from a decrease in the transparency of the pulmonary fields, the appearance of multiple small focal ones to the appearance of large infiltrate-like shadows. Characteristic features of the X-ray picture are sudden onset and relatively rapid reverse dynamics. Frequent exacerbations of the disease lead to the development of interstitial pneumosclerosis [2]. Treatment of patients with hemosiderosis involves the prescription of corticosteroid drugs, and if ineffective, cytostatic drugs (azathioprine, cyclosporine A) [11]. According to Saeed MM et al., who summarized the experience of observing 17 children suffering from idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, the five-year survival rate exceeds 80% [11].

Considering that pulmonary hemosiderosis is a fairly rare disease, below is a case of clinical observation from our own practice.

Patient R., 14 years old, was admitted to the pulmonology department of the Republican Children's Clinical Hospital (RCCH) with complaints of weakness, dizziness, wet cough with the discharge of sputum streaked with blood. I felt a deterioration in my condition about two weeks before hospitalization.

At the time of admission, the child had been ill for two years, when he was first admitted to the Russian Children's Clinical Hospital for examination for moderate iron deficiency anemia. About 4 months later, he consulted a pediatrician with complaints of cough and weakness. With a diagnosis of pneumonia, he was hospitalized in the pulmonology department of the Russian Children's Clinical Hospital, where, as a result of an examination, a general blood test revealed hypochromic anemia of moderate severity (hemoglobin 86 g/l), in the sputum - siderophages characteristic of damage to the interstitial tissue of the lungs, changes on a computed tomogram of the chest organs cells and a diagnosis was made: Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. Iron deficiency anemia of moderate severity. He was regularly observed by a pulmonologist and was treated with glucocorticosteroids (oral prednisolone). At the time of this hospitalization, he had not taken prednisolone for a year.

A child from 2 pregnancies, 2 term births (the first birth ended in stillbirth) by cesarean section with a weight of 2450, a height of 49 cm, an Apgar score of 7-8 points. He grew and developed according to his age. Vaccinations were done according to the calendar. History of rare acute respiratory diseases.

Upon admission, the condition was serious due to the disease, the state of health was moderate. The child is lethargic. Reduced nutrition, proper physique. Weight 37 kg. The skin is pale, dry. The sclera is subicteric. The pharynx is not hyperemic. The cervical and submandibular lymph nodes were palpated, measuring 0.5 cm, soft, elastic, painless. The chest is barrel-shaped. Percussion - dullness in the lower fields of the lungs. Auscultation of the lungs reveals weakened breathing, intermittent moist fine-bubble rales. Respiration rate is 22-24 per minute. The limits of relative cardiac dullness corresponded to the age norm. Heart sounds are clear, the rhythm is correct. Heart rate 90 beats per minute. The abdomen is soft and painless. The liver is at the edge of the costal arch. The spleen was not palpable. Stool and urination are not impaired.

On the 9th day of hospitalization, despite the therapy (systemic glucocorticosteroids, antibacterial therapy, symptomatic therapy), the child experienced a deterioration in his condition, an increase in body temperature to 39-400C, severe weakness, and shortness of breath. The child was transferred to the intensive care unit, where he was on artificial ventilation for 4 days.

Upon admission, a general blood test revealed hypochromic anemia of severe mixed etiology. The number of erythrocytes in the general blood test was 1.99x1012/l, hemoglobin - 45 g/l, hemoglobin content in an erythrocyte - 22.6 pg, hemoglobin concentration in an erythrocyte - 28.1%, erythrocyte volume - 80.4 fl, reticulocyte count – 7.7 0/00. A blood test was performed for iron content, which was 1.85 µmol/l (normal 12.5-32 µmol/l), latent iron-binding capacity - 67 µmol/l (normal 20-62 µmol/l), total iron-binding capacity - 68.9 µmol/l (normal 44.8-76.1 µmol/l), transferrin - 3.04 g/l (normal 1.83-3.63 g/l), transferrin saturation percentage - 2.4% at normal 15-50%, ferritin 66 µg/l (normal 7-140 µg/l).

In addition, on the fourth day of hospitalization, there was an increase in leukocytes to 17.7x109/l, neutrophilia - band 5%, segmented 74%, with a subsequent increase in neutrophilia to 94%. In a biochemical blood test, an increase in hypoproteinemia was noted to 42 g/l (normal 66-87 g/l), hyperbilirubinemia to 67.8 µmol/l (normal 1.7-20.5 µmol/l) due to the indirect fraction. On the 12th day from the moment of hospitalization - acceleration of ESR to 30 mm/h, thrombocytopenia to 100x109/l.

Immunological examination upon admission revealed a decrease in the level of IgG to 4.8 g/l (normal 8-16.4 g/l), a reduced level of CD3+ cells to 28% (normal 52-76%), CD4+ - to 11% (normal 31-46%), CD8+ - up to 21% (normal 23-40%), CD16+ - up to 3% (normal 9-19%), CD25+ - up to 7% (normal 10%). Hyperergic type of chemiluminescent curve.

The blood is negative for HIV infection. Throat smear for flora – single S. aureus, C. albicans. The electrocardiogram shows sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 81-83 per minute. The electrical axis of the heart is not deviated. Incomplete blockade of the right bundle branch. Slows down the electrical systole by 0.06 sec. Echocardiography revealed a congenital heart defect - atrial septal defect, secondary, mitral regurgitation 1+. Slit-like defect of the interventricular septum in the upper third. The cavity of the left ventricle is at the maximum limit of normal. RPH 25 mm Hg. Art.

Study of the gas composition of arterial blood: pH 7.33, pCO2 34 mm Hg. st, pO2 33.3 mm Hg. Art., SaO2 55.2%.

Other indicators of a biochemical blood test (urea, creatinine), urine and feces tests are within the age norm, ultrasound examination of the abdominal organs and kidneys is without any features.

A chest x-ray (CH) at the time of admission revealed focal-like shadows of a confluent nature throughout all pulmonary fields. The pulmonary pattern is enriched, mainly due to the interstitial component. The contours of the mediastinum and the contours of the domes of the diaphragm are not clearly visible.

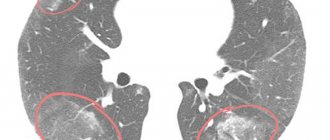

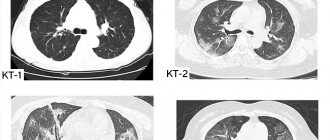

Computed tomography of the OGK revealed a significant decrease in pneumatization of the pulmonary fields. At all levels there are multiple, small-focal, merging with each other into extensive conglomerates, infiltrate-like compactions, with a density reaching up to -370 units N. The pulmonary pattern is enriched, in places deformed, with symptoms of local pneumofibrosis. Strengthening, thickening of the interlobular, peribronchial, perivascular interstitium. Reaction of costal and interlobar pleura. Pleurocostal, pleuromediastinal, supraphrenic adhesions. Enlargement of intrathoracic lymph nodes up to 7-12 mm (Fig. 1, 2, 3).

Figure 1. Overview topogram of the chest organs in a direct projection. Strengthening, deformation of the pulmonary pattern. Periprocess along the bronchovascular structures

Figure 2. Axial CT image of the chest at the level of the tracheal bifurcation. Enlargement of the lymph nodes of the central mediastinum. The retrosternal space of the anterior mediastinum is filled with tissue of the thymus gland

Figure 3. Axial CT image of the chest in the basal-phrenic regions. Multiple small focal compactions merging with each other and forming extensive infiltrate-like overlays

Against the background of the treatment: systemic glucocorticosteroids (pulse therapy, then oral prednisolone), massive antibacterial therapy, infusion therapy, symptomatic therapy, on the 30th day from the moment of hospitalization, clinical stabilization was achieved, the child’s well-being significantly improved. The hemogram indicators (leukocytes 14.6x109/l, erythrocytes 3.54x1012/l, hemoglobin 82 g/l, platelets 370x109/l, ESR - 5mm/h), biochemical blood parameters (total protein 60.7 g/l, total bilirubin 4 µcol/l), positive X-ray dynamics were noted (foci-like shadows disappeared, the pulmonary pattern began to be differentiated more clearly).

On the 42nd day from hospitalization, the child was discharged home with improvement. It is recommended to take systemic glucocorticosteroids on a tapering schedule. Follow-up observation for more than six months demonstrated the absence of exacerbation of the disease in the child.

In conclusion, it must be added that idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis is a disease that is difficult to diagnose and has a serious prognosis. It is often diagnosed only after unsuccessful attempts at antibacterial therapy for “pneumonia.” Timely diagnosis of the disease and the prescription of adequate immunosuppressive therapy can prevent the rapid progression of the process and the development of pneumosclerosis.

D.V. Kazymova, E.N. Akhmadeeva, D.E. Baykov, G.V. Baykova

Bashkir State Medical University, Ufa

Republican Children's Clinical Hospital, Ufa

Akhmadeeva Elza Nabiakhmetovna - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Hospital Pediatrics with a course of outpatient pediatrics

Literature:

1. Artamonov R.G. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis // Medical scientific and educational journal. - 2002. - No. 6. - P. 189-193.

2. Bogorad A.E., Rozinova N.N., Sukhorukov V.S. and others. Idiopathic hemosiderosis of the lungs in children // Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics. - 2003. - No. 4. - P. 29-35.

3. Davydova V.M. Interstitial lung diseases // Practical medicine. Pediatrics. - 2010. - No. 45. - P. 22-28.

4. Fadeeva M.L., Gingold A.M., Shchegoleva T.P. and others. Idiopathic hemosiderosis of the lungs in children // Issues. ocher mat. and children - 1976. - No. 4. - P. 37-42.

5. Yatsenko E.A., Plakhuta T.G., Guzheedova E.A. Iron deficiency anemia as a manifestation of isolated pulmonary hemosiderosis // Pediatrics. - 1991. - No. 6. - 87 p.

6. Cohen S. Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis // Am. J. Med. Sci. - 1999. - Vol. 317. - P. 67-74.

7. Heiner DC, Sears JW, Kniker WT Chronic respiratory disease associated with multiple circulating precipitins to cow's milk // Am. J. Dis. Child. - 1960. - Vol. 100. - P. 500-502.

8. Heiner DC, Rose B. Elevated levels of YE (IgE) in conditions other than classical allergy // J. Allergy. - 1970. - Vol. 45. - P. 30-42.

9. Kjellman V., Elinder G., Garwicz S. et. al. Idiopathic pulmonary hemo¬siderosis in Swedish children // Acta Pediat. Scand. - 1984. - Vol. 73. - P. 584-588.

10. Ogha S., Takahashi K., Miyazaki S. et. al. Idiopathic pulmonary he¬mosiderosis in Japan: 39 possible cases from a survey questionnaire // Eur. J. Pediat. - 1995. - Vol. 154. - P. 994-995.

11. Saeed MM, Woo MS, MagLaughlin EF et. al. Prognosis in pediatric idiopathic pulmonary hemo¬siderosis // Chest. - 1999. - Vol. 116. - P. 712-725.

Treatment of ILD

Considering the low incidence of ILD, the diagnosis and treatment of these diseases should be carried out by pulmonologists with experience in managing such patients.

Treatment of interstitial lung diseases is determined by the specific type of disease. In some cases, if the patient is in good health and there are no changes in pulmonary function, treatment is not prescribed, but the patient is monitored for several months and only when the disease progresses, active therapy is started. In some ILDs, on the contrary, it is necessary to begin powerful treatment immediately after diagnosis to prevent the development of pulmonary fibrosis and restore as much normal lung tissue as possible. Treatment of all ILDs takes from several months to several years, therefore, unlike many other pulmonary diseases - bronchitis, pneumonia - which can result in recovery even without treatment, interstitial lung diseases require close cooperation and mutual understanding between the patient and his doctor. Unauthorized cessation of medication or uncontrolled reduction of doses after improvement of health is fraught with a rapid exacerbation of the disease. By showing excessive independence, the patient nullifies both his and the doctor’s efforts and delays his own recovery.

Despite long courses of treatment, modern medications can minimize the risk of side effects. In the vast majority of cases, today's medicine makes it possible to effectively fight these diseases and return a sick person to a full, happy life.

Diagnostics

The X-ray picture is polymorphic, because it shows manifestations not only of pneumosclerosis itself, but also of associated diseases: emphysema, bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, etc. Typical looping, enhancement and deformation of the pulmonary pattern along the bronchial branches, as the bronchial walls become denser, sclerosis and infiltration of peribronchial tissue occur.

Bronchography shows deviation or convergence of the bronchi, narrowing and absence of small bronchi, and deformation of the walls. Spirography is an effective diagnostic method for suspected pneumosclerosis; it reveals a decrease in VC, FVC, and Tiffno index.

Over the affected area, physical examinations reveal decreased breathing, dry or moist rales, and dullness of percussion sound. Lung examination is also a reliable diagnostic method. Even if there are no symptoms, x-rays help to detect changes if they are present, their nature, prevalence, and how pronounced they are. Magnetic resonance imaging, bronchography, and CT scan of the lungs can more accurately assess the condition of unhealthy areas of lung tissue.

An x-ray shows the following changes in the affected lung:

- reducing it in size

- increased pulmonary pattern along the branches of the bronchi

- the pulmonary pattern is reticulated and looped due to deformation of the bronchial walls

- "honeycomb lung" in the lower sections

Fluorography for pneumosclerosis

If you have any complaints of cough or any respiratory symptoms, you must undergo a fluorographic examination of the chest organs. Every year, in order to prevent and early detect pneumosclerosis, tuberculosis and other similar diseases, all persons over 14 years of age must undergo a medical examination. With pneumosclerosis, the vital capacity of the lungs decreases, and the Tiffno index (which is an indicator of bronchial patency) is low.

Our specialists

Chikina Svetlana Yurievna

Candidate of Medical Sciences, pulmonologist of the highest category. Official doctor, expert at Russian congresses on pulmonology.

30 years of experience

Kuleshov Andrey Vladimirovich

Chief physician, candidate of medical sciences, pulmonologist, somnologist, member of the European Respiratory Society (ERS).

Experience 26 years

Meshcheryakova Natalya Nikolaevna

Candidate of Medical Sciences, pulmonologist of the highest category, associate professor of the Department of Pulmonology named after. N.I. Pirogov.

Experience 26 years

Nikitina Natalia Vladimirovna

Deputy chief physician, pulmonologist, allergist of the highest category. Full member of the European Academy of Allergy and Immunology.

Experience 15 years