Traces of hemoglobin in the urine of adult men, women, and children of all age groups are the first sign of a pathological condition of blood vessels, dysfunctional disorders in the hematopoietic system, kidney disease and other organs of the excretory system.

The appearance of signs of hemoglobin in urine indicates intravascular hemolysis of red blood cells, as well as a gradual change in the cellular composition of the blood. This is a dangerous symptom that can occur due to the presence of hematological factors, as well as due to the negative influence of external factors.

How and under what conditions is it formed in urine?

Traces of hemoglobin in the urine of men, women and children should be completely absent. The appearance of this substance in urine is called hemoglobinuria. In the bloodstream of healthy people, on average, about 10% of all red blood cells are destroyed, which release free hemoglobin.

In this regard, the blood plasma contains about 4 mg% of this protein compound. Free hemoglobin actively interacts with haptoglobin, forming strong biochemical bonds. This compound is not able to overcome the kidney filter, since its molecular weight ranges from 160 to 320 kDa.

The molecular complex, consisting of free hemoglobin and haptoglobin, enters the tissues of the liver and spleen, where it undergoes chemical decomposition with the formation of final metabolites of pigment metabolism.

If in the human body these biochemical processes proceed stably, and the kidneys, liver and spleen perform their functions, then hemoglobin molecules do not penetrate into the urine, as they break down into their constituent substances inside the body. Hemoglobinuria develops only when a critical amount of free hemoglobin (over 100 mg%) enters the blood plasma.

Haptoglobin, which is found in the bloodstream, is not able to bind excess concentrations of free hemoglobin, which entails its active reabsorption by kidney cells.

Absorbed hemoglobin accumulates in the epithelial tissues of the proximal canals, and then, through the process of chemical oxidation, can be converted into the substances hemosiderin and ferritin. Part of the absorbed hemoglobin enters the urine, which is subsequently detected during laboratory testing for biochemical parameters.

Traces of hemoglobin in the urine of women, men and children appear after prolonged or short-term exposure to external factors, or are one of the symptoms of a painful condition of internal organs. The table below details conditions the presence of which can lead to the formation of free hemoglobin in urine.

| Factors influencing the appearance of traces of hemoglobin in urine | Description of pathological processes |

| Nocturnal hemolysis of red blood cells | In this case, hemoglobin enters urine exclusively at night, when a person is sleeping and the pH of his blood is at a lower level. This pathological condition of the body is caused by the presence of a hematological disease in the form of acquired anemia, a type of which is extremely rare in medical practice. Mass death of red blood cells occurs in attacks. In the shortest possible period of time, a large amount of free hemoglobin is released into the blood plasma. The tissues of the liver and spleen are not able to ensure the rapid binding and breakdown of this substance. Such hemoglobinuria most often occurs in men and women whose age ranges from 20 to 40 years. Nocturnal hemolysis of red blood cells is associated with heavy physical activity, chronic infection, intoxication of the body, and the consequences of prolonged use of iron-containing drugs. After eliminating the negative influence of external and internal factors, urinalysis indicators stabilize, and free hemoglobin ceases to saturate the blood plasma. |

| Severe intoxication of the body | Contact with chemical or biological substances, overdose of potent drugs that have toxic properties can lead to massive hemolysis of red blood cells. In this regard, a sharp change in the cellular composition of the blood occurs, the death of red blood cells with the release of free hemoglobin. This is a dangerous condition of the body that requires emergency treatment measures. |

| Continuous static load | Traces of hemoglobin in urine can periodically appear in absolutely healthy people who have been on their feet for a long time or have traveled long distances on foot. Similar symptoms are often found in soldiers practicing marching formation, travelers, and athletes who engage in race walking or marathon running. In this case, hemolysis of red blood cells is associated with a static effect on the plantar part of the foot, the consequences of which are damage to red blood cells with the release of excess amounts of free hemoglobin. Traces of protein compounds are not found in urine after a short rest and recovery of the body. |

| Negative effects of cold | After prolonged swimming in cold water or hypothermia due to being in the open air, paroxysmal hemoglobinuria develops. The amboceptor hemolysin is formed in human blood, which binds to red blood cells, causing their premature hemolysis. The danger of the pathological process lies in the fact that with severe hypothermia, changes in the cellular composition of the blood can be irreversible. Once normal body temperature is restored, signs of free hemoglobin in urine disappear in humans. On average, this occurs after 24-48 hours. |

| Autoimmune reaction | This reason for the appearance of traces of hemoglobin in urine is very rare. The conditions for the development of a pathological state of the body are due to the fact that the cells of the immune system regard red blood cells as foreign and extraneous agents. Red blood cells are constantly under attack, which ultimately leads to an increase in the level of free hemoglobin, the detection of traces of it in the urine and the development of severe anemia. |

| Blood transfusion | In the case of transfusion of donor blood, which has an incompatible antigenic structure, acute hemolysis of red blood cells develops with the release of large amounts of hemoglobin. The protein compound saturates the composition of urine, and the symptoms of hemoglobinuria persist for several days. |

| Diseases of infectious origin | Bacterial pathogens of diphtheria, typhoid fever, syphilis, scarlet fever cause the death of red blood cells and the appearance of an excess amount of free hemoglobin. As the patient recovers, the biochemical composition of urine stabilizes. |

| Pathologies of the genitourinary system | Acute inflammatory diseases of the tissues of the kidneys, bladder and urethra can lead to destruction of their structure and the appearance of ulcerative formations. Hemolysis of red blood cells is caused by local secretions of blood and the breakdown of its cells. After eliminating the underlying disease, traces of free hemoglobin in the urine disappear |

Regardless of the conditions under which hemoglobin molecules appear in urine, its presence indicates a diseased state of the body. A person with a similar symptom should undergo a comprehensive examination aimed at detecting pathology.

When should you take a general urine test during pregnancy?

OAM should be taken on the recommendation of a gynecologist or other attending physician, regardless of the presence of complaints.

You can donate urine yourself before visiting a gynecologist for the following reasons:

- increase in body temperature

- chills

- malaise, weakness, headaches, depressed mood

- pain or discomfort in the lower back or abdomen

- cloudy urine with an unpleasant odor

- pain and difficulty while urinating

- feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder and urinary retention

Symptoms

Traces of hemoglobin in the urine of women, men and children are detected by the results of a study of the constituent components of urine.

Signs of pathology appear as follows:

- frequent urge to urinate;

- attacks of spasmodic pain in the lumbar spine from the side of the kidneys;

- urine takes on a rich dark brown hue;

- decreased physical activity;

- fast fatiguability;

- dizziness and a feeling of lack of air (occurs with severe hemoglobinuria, which led to the development of chronic anemia);

- headache;

- decreased blood pressure;

- pale skin;

- drowsiness.

Most patients who have traces of hemoglobin in their urine do not always experience the full list of these symptoms. The presence of this protein substance can be diagnosed completely by chance based on the results of a routine examination.

Especially if there are chronic foci of bacterial infection in the human body, he plays intensive sports, comes into daily contact with chemicals of toxic etiology, or takes medications with hemolytic properties.

Characteristics of forms of hemoglobinuria

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

A distinctive feature of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (Marchiafava-Miceli disease) is attacks of intravascular hemolysis (hemolytic crises), developing mainly at night. The disease is registered with a frequency of 1:500,000. Hemolytic crises can be provoked by hypothermia, infection, vaccination, blood transfusions, physical activity, and surgical interventions.

Paroxysms of hemolysis of red blood cells are accompanied by fever, arthralgia, drowsiness, chest pain, abdominal and lower back pain. Signs of increasing iron deficiency anemia are general weakness, yellowness of the skin and mucous membranes. Characterized by enlargement of the liver and spleen. Dark-colored urine is observed in only a quarter of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

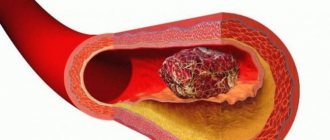

The most dangerous manifestations of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria are thrombosis of mesenteric vessels, renal vessels, and peripheral vessels. Thrombosis of the hepatic veins is accompanied by a sharp increase in the size of the liver, progressive ascites, and varicose veins of the esophagus. Persistent hemosiderinuria often leads to tubular nephritis; at the height of a hemolytic crisis, acute renal failure may develop.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria often develops in patients with aplastic anemia, preleukemia or acute myeloid leukemia, and therefore requires a complete hematological examination of the patient.

Morning hematuria is detected in the urine of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

March hemoglobinuria

The symptoms of marching hemoglobinuria are usually more subtle and develop gradually. Chills and fever are uncharacteristic. Weakness is noted, which may also be a consequence of general physical fatigue from the forced march. At the same time, a pathognomonic sign of this form of hemoglobinuria is the dark color of urine. After the cessation of the marching load, the state of health returns to normal, the urine becomes lighter.

It has been noticed that almost all people who are faced with marching hemoglobinuria have pronounced lumbar lordosis. This form of hemoglobinuria has no independent clinical significance.

Cold paroxysmal hemoglobinuria

A rare form of hemolytic anemia - paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria occurs in attacks. Paroxysms of cold hemoglobinuria are usually provoked by hypothermia and are accompanied by hyperthermia (sometimes up to 40°C), severe chills, nausea and vomiting, and abdominal pain. Hepato- and splenomegaly, yellowish color of the skin and sclera, and characteristic color of urine are detected.

Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria caused by acute viral infections usually resolves with the underlying disease. With syphilis and malaria, the disease can last for years.

Indications for the study

Traces of hemoglobin in the urine of women, men and children can only be detected in a biochemical laboratory.

The attending physician prescribes a urine test for the patient for the presence of molecules of this protein substance if there are signs of the following pathologies:

- inflammatory processes in the organs of the genitourinary system, the development of which is accompanied by purulent and sanguineous discharge;

- severe burns of the skin surface affecting more than 30% of the body;

- intoxication of the body caused by prolonged exposure to toxic substances of chemical or biological origin;

- infection with scarlet fever, diphtheria, typhoid fever, malaria, syphilis;

- rejection of donor blood;

- the period of rehabilitation after surgery (the factor of internal bleeding is excluded);

- perforated ulcer;

- severe injuries to the kidneys, liver and spleen;

- prolonged hypothermia of the body;

- all types of anemia.

A urine test for the presence of traces of hemoglobin is carried out during the process of diagnosing the patient, during the course of treatment, and also 1-2 weeks later following the results of recovery. For example, infection with a streptococcal infection requires repeated urine testing 10 days after the symptoms of the disease disappear.

Preparing and conducting analysis

In order for the results of a general urine test to be as reliable as possible, it is recommended to follow the following preparation rules before giving urine:

- on the evening before donating urine, do not eat vegetables and fruits, the natural pigments of which can change the color shade of urine (carrots, cranberries, beets);

- 24 hours before visiting the laboratory, stop taking medications with diuretic properties;

- 3 days before the test do not drink alcohol;

- 12 hours before the examination, do not eat food with a high content of hot spices, the presence of which can lead to irritation of the mucous membrane of the urinary system;

- 5 days before diagnosis, stop taking medications, the side effects of which can lead to hemolysis of red blood cells.

These are the basic rules for preparing for a urine test for signs of traces of hemoglobin. Otherwise, a person must lead a normal lifestyle so that the results of a urine test are objective.

The step-by-step process for taking a test to detect traces of hemoglobin is as follows:

- After waking up from sleep, you must perform thorough genital hygiene using soap, warm water and a clean, dry towel.

- Take a sterile container for collecting urine, which can be purchased directly from a laboratory or pharmacy.

- Flush a small amount of morning urine down the toilet to cleanse the urethra, and then fill a jar with urine for testing.

- Close the container with a lid, and then deliver the biological material for laboratory testing within 1 hour.

On average, at least 50 ml of urine will be required. This is the minimum amount of urine required for this type of analysis.

Women are advised to refrain from donating urine during menstruation, as well as 2 days after the end of menstruation. This is necessary in order to minimize the risk of blood drops getting into the urine. Their presence will lead to distorted results.

M.M. Batyushin, D.G. Pasechnik State Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education Rostov State Medical University of the Russian Health Service, Rostov-on-Don

The concept of Hematuria is the leading symptom in the clinic of pathology of the kidneys and urinary tract. Hematuria refers to the appearance of blood cells (namely red blood cells) or their components (hemoglobin) in the urine. In this regard, the concept of hematuria includes erythrocyturia, hemoglobinuria and hemoglobin cylindruria (excretion of hemoglobin casts in the urine). Normally, during a general analysis, there are either no red blood cells in the urine, or their number when counted in Goryaev’s chamber does not exceed 1–2 elements in the field of view. Sometimes a higher number of red blood cells may be normal. This may be due, for example, to intense physical activity. Such episodes are short-lived. The appearance of 3 or more red blood cells in the field of view is considered erythrocyturia. There is no clear definition of persistent erythrocyturia, however, an increase in the number of red blood cells in the urine and persistence according to the results of three or more tests can be conditionally considered persistent erythrocyturia. In the case of erythrocyte adhesion and hemoglobin precipitation in the lumen of the renal tubules, the formation of erythrocyte and hemoglobin casts, which have a characteristic appearance and are stained red with hematoxylin, is possible. As part of the definition of hematuria, micro- and macrohematuria are distinguished. Microhematuria (more correctly, microerythrocyturia) refers to erythrocyturia that does not lead to a change in the color of urine, assessed by eye. With gross hematuria, the urine becomes red (from light pink to cherry). It may be diffusely colored or have blood clots. Thus, the concept of micro- or macrogematria is a qualitative symptom assessed visually. Previously, the phenomenon of “leached erythrocytes” was widely used in the differential diagnosis of erythrocyturia. It is now generally accepted that red blood cell leaching is related to the physicochemical properties of urine. Often, with undoubted renal origin of hematuria, fresh red blood cells are found; on the other hand, gradual leaching of red blood cells can occur when urine is stored for several hours before examination. In this regard, the phenomenon of “leached erythrocytes” should not be leading in differential diagnosis and retains a certain significance only when using phase-contrast microscopy. Hemoglobinuria develops due to the excretion of free extra-erythrocyte hemoglobin in the urine through glomerular filtration. Due to the oxidation of hemoglobin and its conversion into hemosiderin, which is a black pigment, urine with hemoglobinuria and hemosiderinuria may acquire a dark cherry color.

Prevalence The prevalence of erythrocyturia in the population ranges from 0.18 to 16.1%. According to our data obtained during a one-time study of 1446 patients in somatic hospitals in Rostov-on-Don (the study did not include patients from the departments of nephrology and urology), erythrocyturia was detected in 3.7% of cases. When examining young soldiers, P. Froom et al. found erythrocyturia in 39% of cases. However, it was transient in nature, since during subsequent examinations it occurred with a frequency not exceeding 16%. In postmenopausal women, erythrocyturia occurs with a frequency of 13%. In screening studies in pediatric populations, hematuria occurs with a frequency of 1–4% and increases with age, reaching 12–18% in adolescence.

Causes of hematuria and pseudohematuria Pseudogematuria Not every phenomenon of red urine is hematuria. Redness of urine not accompanied by erythrocyturia and/or hemoglobinuria is called pseudohematuria. Pseudohematuria can be caused by taking a number of medications, food nutrients, and chemicals that color it red (Table 1).

Table 1. Causes of pseudohematuria

| Urine color | Cause |

| Red | Antipyrine, amidopyrine, santonin |

| Pink | Acetylsalicylic acid in large doses, carrots, beets |

| Brown | Phenol, cresol, bears ears, activated carbon (carbolene), urates, porphyrins |

| Dark brown | Salol, naphthol |

In addition, it is possible to verify hematuria that does not actually exist due to a laboratory error or deliberate distortion of the result of a urine test, but the latter is extremely rare. This phenomenon should also be interpreted as pseudohematuria.

Hematuria of extraurinal origin If pseudohematuria is excluded, the next step in the differential diagnosis should be the exclusion of hematuria of extraurinal origin. In this case, we are talking about blood getting into the urine not from the kidney and urinary tract, but from other organs, as well as from the outside. The following types of hematuria of extraurinal origin include:

simulated hematuria:

- blood is added to the urine after urination from a wound inflicted by the simulator on a finger, lip, scrotum, etc., as well as the blood of another person;

- blood is introduced into the bladder through a catheter before urination;

- a foreign object injures the mucous membrane of the urethra before urination;

- the malingerer’s urine is mixed with the urine of a patient suffering from kidney pathology, manifested by hematuria.

hematuria of genital origin:

- taking a urine test during menstruation, as well as the day before or within 3-4 days after its end;

- bleeding from tumors of the uterus, vagina, atrophic colpitis;

- formation of vesico-uterine anastomosis (tumor, traumatic);

- preservation of menstruation with desquamation of the functional layer of the mucous membrane of the cervix during supravaginal amputation of the uterus;

- hematuria in pregnant women;

- postcoital hematuria.

hematuria of rectal origin:

- bleeding from a hemorrhoid;

- bleeding from anal fissure;

- rectal cancer;

- chronic proctosigmoiditis with the opening of a fistula in the perianal region, vesico-rectal anastomosis.

hematuria of perineal origin:

- boil, perineal carbuncle;

- perineal injuries.

During screening examinations of pregnant women, hematuria is observed in 20% of cases. Moreover, in 53% of cases it is detected before the 32nd week of pregnancy. Its appearance is a risk factor for the development of complications during childbirth and is usually due to obstetric reasons (threat of miscarriage, premature birth, premature abruption of the low-lying placenta, etc.). Postcoital hematuria is characterized by the appearance of erythrocyturia in a portion of urine given immediately after sexual intercourse. We observed 10 patients who had erythrocyturia after coitus. In 4 cases, erythrocyturia appeared after the introduction of foreign bodies into the urethra, and in one case gross hematuria was observed. It can be assumed that this cause of hematuria is not rare, but due to its delicacy it is rarely considered when carrying out differential diagnosis. In 6 cases, the cause of erythrocyturia was prostate disease and the patients were referred for examination and treatment to a urologist. As a rule, postcoital hematuria is combined with hemospermia. Isolated hemospermia and isolated postcoital hematuria are possible. The latter is an extremely rare option. Variants of isolated postcoital hematuria caused by a urethral polyp are described. Combined postcoital hematuria and hemospermia in young men in most cases is caused by the presence of benign papillary adenoma, in older men - prostate cancer. Isolated hemospermia in 40% of cases is caused by prostate infection; a malignant tumor also occurs; in some cases, the cause cannot be determined. Simulating pseudohematuria is not widespread due to the lack of difficulties in most cases in differentiating it from true hematuria. Their appearance is due to the motivation of malingerers and aggravators to enhance or direct the clinical manifestations of the disease in order to achieve some social benefits. Understanding the motive for malingering or aggravation is key to a successful differential diagnosis. Most often, elements of aggravation or simulation are observed in expert practice when conducting military medical, medical, social or forensic examinations.

True erythrocyturia There are many reasons for the development of erythrocyturia. There are no less attempts to classify this phenomenon. The appearance of red blood cells in the urine may indicate the development of pathology of the kidneys and urinary organs, as well as the genital organs. In 65% of patients, erythrocyturia is of extrarenal origin. The pathogenesis of renal anemia is poorly understood. A possible cause is the formation of damage in the basement membrane of the glomeruli, the so-called breaks or gaps. When the size of the defects exceeds 0.25 microns, red blood cells move through the membrane into the urinary space through them under the influence of intracapillary pressure and retraction forces. In this case, severe deformation and damage to the membranes of erythrocytes occurs, which explains the dysmorphism of these cells in the glomerular type of hematuria. Among the causes of hematuria, infectious, traumatic, autoimmune, toxic, tumor and mixed are distinguished. The classification of R.Cohen and R.Brown (2003) seems to us to be the most acceptable. When hematuria is detected, the diagnostic search is aimed at identifying these diseases. Noteworthy is the fact that hematuria is only one of the symptoms of the disease. The appearance of other symptoms often accompanies hematuria and forces the doctor to analyze their relationship and diagnostic significance. The classification of hematuria, distinguishing symptomatic and asymptomatic forms, is very conditional and is of an exclusively applied nature. Asymptomatic hematuria occurs in the adult population with a frequency of 0.19–21%. In approximately 10–12.1% of cases, it is caused by cancer of the kidneys and urinary tract. In this case, macrohematuria occurs in 3/4 of cases. As literature data show, in 39–90% of cases, the detection of asymptomatic hematuria is not subsequently accompanied by a diagnostic search. According to our data, only in 8% of cases the detection of asymptomatic hematuria led to further examination of patients (n=1446). In childhood, asymptomatic hematuria is most often caused by thin membrane disease (27.5% of all cases of asymptomatic hematuria) and IgA nephropathy (26.2% of all cases of asymptomatic hematuria). Of the glomerulopathies, the most common causes of gross hematuria in children are IgA nephropathy (54.2%) and Alport syndrome (25%). Among non-glomerular causes of hematuria, the most common are hypercalciuria (16%), urethrorrhagia (14.3%), and hemorrhagic cystitis (12.5%). An unidentified cause appears in 46% of cases.

Let's look at some of the causes of hematuria. 1. Urolithiasis Urolithiasis is the cause of 20% of all cases of hematuria. Hematuria with it is intermittent or persistent in nature and can be represented by both micro- and macrohematuria. In case of urolithiasis, Pasternatsky syndrome is described in the form of the appearance of erythrocyturia after walking or tapping the lumbar region. More often, hematuria is combined with pain in the lumbar region or flanks. The cause of hematuria is trauma to the mucous membrane of the urinary tract.

2. Tumors of the kidney and urinary tract Kidney tumors account for about 3% of all human tumors. 85–90% of all cases of oncological processes in the kidney are renal cell carcinoma, which develops from the epithelium of the proximal tubule. Of the benign neoplasms, angiomyolipoma, adenoma and oncocytoma predominate (6–8%). In 40–70% of cases, the disease is asymptomatic. In 5% of cases, the cause of microhematuria is cancer of the kidney and urinary tract. The risk of the latter increases with the patient's age, as well as in the presence of risk factors such as smoking, use of phenacetin, herbs containing aristolochic acid, and cyclophosphamide in high doses. Hematuria is a typical symptom of a tumor. Both micro- and macrohematuria, isolated or less often in combination with low proteinuria, can be observed. With gross hematuria, blood clots are often observed in the urine. Hematuria may be accompanied by pain (pain in the flank, hypochondrium, lumbar region, along the ureter), and may be asymptomatic. With kidney cancer in men, a varicocele may be observed, caused by compression of the testicular vein by the tumor. Paraneoplastic syndrome may develop, observed in 35% of patients. With prostate stromal tumors, hematuria occurs in approximately 14% of cases. The disease develops mainly in older men. The clinical picture of prostate cancer is caused by tumor growth and bladder outlet obstruction and is manifested by micro- and macrohematuria, chronic ischuria, stranguria, pain in the perineum and suprapubic region. Tumors of other locations are also possible: bladder, ureter, urethra.

3. Glomerulonephritis Hematuria is one of the clinical manifestations of acute, chronic and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. It is part of the nephritic syndrome. Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis always manifests itself as isolated hematuria or hematuria in combination with proteinuria; urinary syndrome in chronic and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis can occur without hematuria (proteinuric variant, nephrotic syndrome). Hematuria occurs in various morphological variants of nephritis, less often in minimal change disease and membranous glomerulonephritis. Hematuria with glomerulonephritis is usually preserved if other causes of hematuria are excluded, as well as in the presence of criteria for nephritic syndrome (hypertension, overhydration). Hematuria is observed both in idiopathic variants of glomerulonephritis and in its development as part of systemic connective tissue diseases (collagenosis, systemic vasculitis, arthropathy).

4. Connective tissue diseases Kidney damage in systemic vasculitis is varied and is represented by renal angiitis, interstitial nephritis and fibrosis with or without areas of necrosis, and various types of glomerulonephritis. The appearance of erythrocyturia in systemic vasculitis is evidence of the involvement of the kidneys or urinary tract in the pathological process. Differential diagnosis is usually aimed at excluding vasculitis, guided by criteria developed and widely used in rheumatological practice. In addition to systemic vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, arthropathy such as gout, rheumatoid arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis are often the causes of hematuria (Fig. 6).

5. Polycystic kidney lesions Polycystic kidney lesions may be accompanied by hematuria. It is usually asymptomatic. Clinical manifestations appear in the case of the development of infectious complications, as well as chronic renal failure.

6. Tubulointerstitial nephritis Interstitial nephritis of toxic origin Develops due to the effects of exo- and endotoxins on renal tissue. This group of kidney damage is diverse and includes exposure to industrial substances and household chemicals, medicinal and other substances.

Drug-induced interstitial nephritis The problem of drug-induced kidney damage is one of the pressing problems of modern nephrology. Approximately 6–60% of all cases of acute renal failure (ARF) are due to interstitial nephritis, as determined by nephrobiopsy. In half of the cases, the etiology of acute interstitial nephritis is drugs. Interstitial nephritis most often develops in response to antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are the cause of 44% of cases of acute interstitial nephritis, antibiotics – 33% of cases. Cases of interstitial nephritis have also been described during therapy with warfarin, thiazide diuretics, indapamide, mesalazine, ranitidine, and cimetidine. Erythrocyturia is present in 87–100% of cases when examining urinary sediment in acute drug damage and in 43–56% of cases in chronic cases.

Other drug-induced damage to the kidneys and urinary tract, accompanied by erythrocyturia

- Papillary necrosis - can be caused by NSAIDs, aspirin, analgin.

- Hemorrhagic cystitis - caused by cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, mitotane.

- Urolithiasis - may occur when taking carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, dichlorphenamide, indinavir, mirtazapine, ritonavir, triamterene.

- Tumors of the urinary tract - can occur during therapy with cyclophosphamide, analgesics (phenacetin).

- Drug-induced vasculitis.

Interstitial nephritis due to herbal medicine Nephropathy due to the intake of Chinese herbs is known under the term “chinese herb nephropathy”. It is characterized by rapid progression of chronic renal failure (CRF) and is manifested morphologically by extensive interstitial fibrosis without glomerular damage. Occurs in women taking Chinese herbal supplements. Nephrotoxicity is determined by the presence of aristolochic acid in herbs. A cumulative dose of Aristolochia fangchi extract from the site of Stephania tetrandra has been shown to result in the development of CRF in 30.8% of cases. Erythrocyturia is one of the manifestations of the disease.

7. Congenital anomalies of the urinary tract Most often, hematuria is observed with nephroptosis, ureteral stricture, compression of the ureteropelvic segment or group of calyces by an aberrant renal artery, as well as with complete and incomplete duplication of the kidney, renal venous hypertension. The main cause of hematuria in patients with congenital anomalies is an increase in intrapelvic urine pressure due to compression and impaired urine outflow from the pelvis. As a result, microtraumatization of the mucous membrane of the pelvis develops with the development of microhematuria. With venous hypertension, venule ruptures with the development of microbleeding are observed. Typically, hematuria is recurrent and combined with renal colic or dull and weak flank and lumbar pain.

8. Infectious diseases Pyelonephritis, cystitis, prostatitis In some cases, erythrocyturia can be observed with pyelonephritis. It always occurs against the background of leukocyturia and is often caused by an unfavorable background in the form of a congenital anomaly of the urinary tract, urolithiasis, etc. With cystitis, erythrocyturia may be the only laboratory phenomenon. Prostatitis often leads to a combination of erythrocyturia and leukocyturia. In 10% of cases, isolated microhematuria is possible.

Septic nephropathy With sepsis, according to various sources, septic nephropathy develops in 10–45% of cases. It can be represented by septic acute glomerulonephritis, chronic glomerulonephritis, acute interstitial nephritis, tubular or cortical necrosis, renal carbuncle, apostematous nephritis and pyelonephritis, thrombosis of the renal arteries and veins. A wide range of possible injuries dictates the need for detailed differential diagnosis.

Tuberculosis With tuberculosis of the genitourinary system, epididymitis (58.1%) and kidney damage (16.3%) most often develop, less often than other organs: orchitis (9.3%), cystitis (7%), urethritis (4.7%) , damage to the prostate (2.3%), testicular membranes (2.3%). Tuberculosis of the kidney and urinary tract is manifested by erythrocyturia. Moreover, ultrasound or urographic imaging often reveals gross structural changes in these organs. Often a combination of tuberculosis of the kidneys and lungs.

Schistosomiasis An infection caused by a schistosome, most often Schistosoma haematobium. Distributed in the countries of Western (Benin, Burkina Faso, Gambia, Mali, Nigeria, Chad), Southern (Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia) and Northern (Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan) Africa, also found among tourists who visited these countries . Less commonly, infection is caused by S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. intercalatum and S. mekangi. Fever (44%), diarrhea (40%), itching (25%), chills (21%), and hematuria (20%) develop. Hypereosinophilia is observed in 82% of cases, increased liver enzymes – in 82%. Schistosomes are found in urine and stool in 60% of cases. With schistosomiasis, damage to the bladder is observed. Ultrasound examination reveals a change in the contours of the bladder wall, wall thickening of more than 5 mm, and visualization of a shadow in the form of a pseudopolyp. In this case, hematuria is a mandatory phenomenon.

Leptospirosis A zoonotic infection caused by Leptospira icterohaemorrhagia (50% of cases), L. canicola (41.4%), L. pomona (2.3%), L. grippotyphosa (5.5%), L. tarassovi (0.8% ). The most common sources of infection are rodents and dogs. Kidney damage in the anicteric form of leptospirosis is observed in 36.2% of cases and is represented by lower back pain (17.1%), a slight decrease in diuresis (21.3%), an increase in creatinine (12.8%), changes in urine tests (erythrocyturia , leukocyturia, low proteinuria). Morphological examination reveals interstitial nephritis. Jaundice forms are more severe and in 66.7% of cases are accompanied by the development of acute renal failure. Kidney damage in the icteric form is observed in 92.6% of cases. In this case, the clinical manifestations of kidney damage are most pronounced on the 5th–6th day of the disease.

Virus-associated nephropathies Kidney damage has been described in infections caused by hepatitis A, B, C viruses, HIV, parvovirus B 19, cytomegalovirus, Coxsackie virus B, Epstein-Barr virus, polyoma virus, hantavirus, adenovirus. Parvovirus infection is associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, Coxsackie virus with IgA nephropathy, polyoma and hantaviruses with interstitial nephritis, hepatitis C virus with glomerulonephritis as part of cryoglobulinemic vasculitis.

9. Hematuria due to venous hypertension Nutcracker syndrome Nutcracker syndrome develops due to compression of the left renal vein between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery [29]. The clinical manifestation of Nutcracker syndrome is hematuria, which develops as a result of venous intrarenal hypertension. According to WHO, varicocele occurs in 36% of men. Moreover, in 43% of cases of varicocele, hypertension is detected in the left renal vein [8]. The causes of varicocele development are aortomesenteric, less often retroaortic compression of the left renal vein, stenosis of the left renal vein. Changes in the kidney with venous hypertension are referred to as phleborenohypertensive nephropathy.

Montenbaker's hematuria ( Mountainbiker ), or physical effort hematuria Physical effort hematuria can be of renal and cystic origin. Most often develops after running. Cases of its development with minimal physical activity have been described.

10. Kidney infarction The main cause of kidney infarction is atherosclerosis of the aorta. The rupture of an unstable plaque is accompanied by the release of nuclear fragments rich in cholesterol into the blood, with the development of cholesterol embolism of the renal vessels. The absence of signs of cardiac pathology during renal infarction is confirmed by detailed examination in approximately 59% of cases. In this case, we are talking about idiopathic renal infarction. However, aortic atherosclerosis can occur without clinically manifested coronary atherosclerosis. Risk factors for cholesterol embolism are acute and chronic forms of coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, as well as atrial fibrillation of various origins, old age, diabetes mellitus, and a history of cerebral stroke.

11. Injuries to the kidney and urinary tract Traumatic injuries to the kidney and urinary tract are observed with impacts and compression of the lumbar region and pelvis. Micro- or macrohematuria is observed. Bleeding from the upper urinary tract can lead to the development of bladder tamponade. The appearance of blood clots is characteristic. Traumatic hematuria also develops during catheterization of the bladder, cystoscopy, catheterization of the ureter, urological operations, and kidney biopsy. In the latter case, microhematuria is observed the next day in 70% of patients, macrohematuria – in 3–5% of patients.

12. Coagulopathy Acquired coagulopathy is caused by the use of warfarin and direct anticoagulants. This occurs in approximately 3–15% of cases and usually resolves after reducing the drug dose. Renal bleeding is less common (0.5–3% of cases). The appearance of hematuria in DIC syndrome in the hypocoagulation phase is explained by the development of microinfarctions in the renal parenchyma and the capillary type of bleeding. Among congenital coagulopathies, hemophilia (A, B, C) and von Willebrandt's disease lead to micro- and macrohematuria. Administration of cryoprecipitate or concentrate of factor 8, 9 or 11 or fresh frozen plasma stops renal bleeding in hemophilia.

13. Rare causes of hematuria Tuberous sclerosis Tuberous sclerosis is a dominantly inherited disease with multifocal damage to the body. Hamartiasis (hamartomas) develops, affecting the skin, heart, kidneys, eyes, and brain. In approximately 80% of cases, a mutation of the TSC1 or TSC2 gene is observed. Kidney damage in tuberous sclerosis occurs in the form of angiomyolipoma, cysts or renal cell carcinoma). Renal manifestations are asymptomatic hematuria, less often - pain in the lumbar region, renal bleeding.

Sarcoidosis and kidney damage Most often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Frequency: 1 case per 2,500–10,000 people. Kidney damage is observed in 1% of cases, but during autopsy it increases to 20%. Three types of kidney damage have been described: nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis, glomerulonephritis and granulomatous lesions (interstitial nephritis, destruction of renal parenchyma).

Psoriasis Kidney damage in psoriasis is rare. It is manifested by tubular dysfunction (47.5%), oxaluria (45%), uraturia (6%), leukocyturia (12%), according to some data, 50% of patients have a decrease in nitrogen excretory function of the kidneys (N.N. Panasyuk, 1988 ). Erythrocyturia is a common manifestation of psoriatic nephropathy. In the case of nephritis, IgA nephropathy is most often recorded.

14. Hemoglobinuria Hemoglobinuria is observed in hemolytic anemia in the case of the development of intravascular hemolysis. Acute intravascular hemolysis develops with the toxic effects of hemolytic poisons (viper venom, acetic acid, etc.), infusions of hypertonic or hypotonic solutions, sepsis, trauma (crash syndrome). In the first hours, the urine is red or pink, and later becomes brownish or black (hemosiderinuria). Under microscopy, erythrocyturia sediment is usually not observed. There may be cases of paroxysmal hemoglobinuria - paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (Marchiafava-Micheli disease). Thus, a wide range of pathological conditions that can cause hematuria requires a detailed diagnostic search with the involvement of urological and nephrological specialists. The most common mistakes when examining hematuria are the following.

- Lack of search for the causes of hematuria (in 92% of cases - own data);

- Incorrect interpretation of the cause of hematuria (chronic pyelonephritis, lack of interpretation);

- Refusal of endoscopic examination (cystoscopy, ureteroscopy);

- Refusal to perform renal nephrobiopsy with a probable diagnosis of chronic glomerulonephritis (12% of refusals – own data).

Conducting a narrow screening search If it is impossible to further examine a patient with hematuria in the medical institution where you work, the patient must be referred to a specialist with a wide range of diagnostic capabilities.

Conclusion In the process of managing a patient with the phenomenon of hematuria, it is necessary to use a wide range of studies, but their choice must be clearly related to the diagnostic hypothesis. Despite the great diagnostic capabilities of modern medicine, in approximately 5–9% of cases the cause of hematuria remains unclear. Often, long-term observation of such patients is not accompanied by verification of the diagnosis. The variety of diseases manifested by hematuria and the clinical features of the course and development of these pathological processes dictate the need for an integrated approach based on solid knowledge in the field of therapy, urology, oncology, gynecology, infectious pathology and toxicology. The wide occurrence of hematuria in outpatient therapeutic practice determines the relevance of the presented topic.

Literature 1. Alekseeva E.A., Antonova T.V. Kidney damage in anicteric and icteric forms of leptospirosis. Nephrology. 2002; 4:74–8. 2. Alyaev Yu., Krapivin A. Choice of diagnostic and therapeutic tactics for kidney tumors. Tver: Triad. 2005. 3. Berman R.E., Vaughan V.K. Pediatrics (director), book. 5. 1993; 314. 4. Eliseeva L.I., Varennikova E.I., Kurinnaya V.P., Shcherbinina I.G. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis: diagnostic problems. Nephrol. and dialysis. 2002; 4 (2). 5. Mukhin N.A. (ed.) National Guidelines for Nephrology. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2009. 6. Panasyuk N.N. Kidney damage in psoriasis. Ter. arch. 1988; 6:130–4. 7. Strakhov S.N., Spiridonov A.A., Prodeus P.P. and others. Changes in the renal and testicular veins in left-sided varicocele and the choice of surgical method in children and adolescents. Urol. and nephrol. 1998; 4:13–8. 8. Strakhov S.N., Burkov I.V., Spiridonov A.A. Nephropathy of phlebohypertensive origin and the choice of treatment method for varicocele in children and adolescents. Nephrol. and dialysis. 2001; 3 (4). 9. Tareeva I.E., Nikolaev A.Yu., Androsova S.O. Nephrology. 1995; 3. 10. Tareeva I.E., Androsova S.O. The effect of non-narcotic analgesics and NSAIDs on the kidneys. Ter. arch. 1999; 4: 17–22. 11. Abdel-Wahab MF, Ramzy I, Esmat G et al. Schistosoma haematobium infection in Egyptian schoolchildren: demonstration of both hepatic and urinary tract morbidity by ultrasonography. J Urol 1992; 148: 346–50. 12. Agbessi CA, Bourvis N, Fromentin M et al. La bilharziose d'importation chez les voyageurs: enquête en France métropolitaine. Rev Med Interne 2006; Jun. 13. 13. Albersen M, Mortelmans LJ, Baert JA. Mountainbiker's hematuria: a case report. Eur J Emerg Med 2006; 13: 236–7. 14. Aliabadi H, Cass AS, Gleich P. Utricular papilloma. Urology 1987; 29: 317–8. 15. Anagnostopoulos GK, Doriforou O, Sakorafas G, Missas S. Tuberous sclerosis associated with giant bilateral bleeding angiomyolipomas. Postgraduate Med J 2004; 80: 580. 16. Belfer MH, Stevens RW. Sarcoidosis: a primary care review. Am Fam Phys 1998. 17. Bolderman R, Oyen R, Verrijcken A et al. Idiopathic renal infarction. Am J Med 2006; 119 (4): 356. 18. Brown MA, Holt JL, Mangos GJ et al. 'Microscopic hematuria in pregnancy: Relevance to pregnancy outcome. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45 (4): 667–73. 19. Buysen JG, Houthoff HJ, Krediet RT, Arisz L. Acute Interstitial Nephritis: A Clinical and Morphological Study in 27 Patients. Nephr Dial Transpl 1990; 5:94–9. 20. Cameron JJ. Lupus nephritis. Am Soc Nephr 1999; 10: 413–34. 21. Cohen RA, Brown RS. Microscopic Hematuria. New Engl J Med 2003; 348:2330–8. 22. Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns ThDH, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Internat 2001; 59:2069–72. 23. Davison AM, Jones CH. Acute interstitial nephritis in the elderly: a report from the UK MRC glomerulonephritis register and a review of the literature. Nephr Dial Transpl 1998; 13(Suppl. 7): 12–6. 24. Edwards TJ, Dickinson AJ, Natale S et al. A prospective analysis of the diagnostic yield resulting from the attendance of 4020 patients at a protocol-driven haematuria clinic. BJU Int 2006; 97(2):301–5. 25. Enriquez R, Cabezuelo JB, Gonzalez C et al. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis associated with Hydroclorotyazide/Amiloride. Am J Nephrol 1995; 15:270–3. 26. Farrington K, Levison DA, Greenwood RN et al. Renal biopsy in patients with unexplained renal impairment and njrmal kidney size. QJ Med 1989; 70: 221–33. 27. Froom P, Ribak J, Benbassat J. Significance of microhaematuria in young adults. Br Med J (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1984; 288:20–2. 28. Gaughan WJ, Sheth VR, Francos GC et al. Ranitidine-induced acute interstitial nephritis with epithelial cell foot process fusion. Am J Kidney Dis 1993; 22: 337–40. 29. Gorospe EC, Aigbe MO. Macroscopic Haematuria in a 15-year old Male: A Case of Nutcracker Syndrome Managed by Endovascular Stenting. Scient World J 2006; 6:745–6. 30. Herawi M, Epstein JI. Specialized stromal tumors of the prostate: a clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30(6):694–704.

Decoding the results

The results of the examination should be deciphered by the attending physician, who conducts an initial examination of the patient and then prescribes a urine sample. A person who does not have health problems should not have signs of hemoglobin in the urine.

The presence of even a small amount of this substance indicates a painful state of the body.

When to see a doctor

A visit to a general practitioner should take place within the first 24 hours after a person discovers the following symptoms indicating the presence of hemoglobin in urine:

- brown or red urine;

- dizziness and loss of strength;

- rapid physical fatigue;

- pallor;

- feeling of lack of air;

- drowsiness;

- headache;

- prolonged drop in blood pressure;

- cardiopalmus;

- nausea;

- loss of appetite;

- frequent urge to urinate.

The appearance of hemoglobin molecules in urine is just one of the symptoms of the underlying disease, the elimination of which will ensure the stabilization of biochemical processes in the body.

How to get it back to normal

In order to normalize the biochemical composition of urine, as well as to prevent further release of free hemoglobin, it is necessary to eliminate the cause of intravascular hemolysis of red blood cells.

Hemoglobinuria caused by exposure to cold or heavy physical exertion does not require the use of drug therapy. The use of medications is advisable only in the case of intoxicated breakdown of red blood cells or acquired anemia.

Medications

In order to normalize free hemoglobin levels, the following medications can be used:

- Troxerutin - this is an angioprotective agent that strengthens the walls of veins and capillaries, prevents vascular damage and hemolysis of red blood cells (1 capsule is prescribed 2-3 times a day for 1 week, and the average cost of the medication is 165 rubles);

- Active iron is an organic drug that replenishes the physiological loss of hemoglobin while measures are taken to eliminate the causes of hemoglobinuria (the medication is taken at the same time, 1 tablet per day with food, and its cost is 105 rubles per pack);

- Activate iron with lactoferin is a drug that replenishes iron deficiency, and also stabilizes the level of hemoglobin in the blood, normalizes metabolic processes (take 1 tablet per day, and the average price of the drug is 550 rubles for 20 tablets);

- Detralex is a medicine that stabilizes the condition of capillaries, prevents vascular damage and hemolysis of red blood cells (1 tablet per day is prescribed, and the cost of the medicine is 230 rubles for a blister of 10 tablets).

The above drugs help prevent further breakdown of red blood cells, maintain the tone of the walls of blood vessels, and stabilize hemoglobin levels. Without eliminating the main causes that change the biochemical composition of blood and urine, the use of these medications will not have a lasting therapeutic effect.

Traditional methods

Traditional medicine is not able to influence the stabilization of free hemoglobin levels. Therefore, their use is not advisable.

Other methods

If it is necessary to carry out emergency treatment measures to stabilize the cellular composition of the blood, the method of hematological transfusion is used. The patient is given a transfusion of donor blood components to saturate the body with additional red blood cells.

The treatment procedure is performed in a hospital inpatient department. Hematological transfusion is indicated for use in patients who have experienced massive hemolysis of red blood cells with critical loss of hemoglobin and the risk of death.

Possible complications

Patients with traces of hemoglobin in their urine should undergo a thorough examination with further treatment of the underlying disease.

The lack of qualified therapy can lead to the development of the following complications:

- rapid weight loss;

- decreased ability to work;

- erectile dysfunction in men;

- digestive dysfunction;

- development of hemolytic anemia;

- functional disorders in the kidneys;

- thrombosis of the great vessels;

- pulmonary hypertension;

- bone marrow failure;

- aplastic anemia;

- oxygen starvation of the tissues of internal organs caused by a constant deficiency of hemoglobin;

- progressive hemolysis of red blood cells with a radical change in the cellular composition of the blood;

- the onset of death caused by vascular thrombosis, impaired renal function and severe anemia.

Traces of hemoglobin in the urine of women, men and children are determined by biochemical examination of urine. The appearance of molecules of this protein compound indicates a disruption in the functioning of the organs of the hematopoietic system, kidneys, liver and spleen tissues, exposure to particularly dangerous toxic substances, heavy physical exertion or prolonged hypothermia of the body.

Traces of hemoglobin in the urine appear due to the massive death of red blood cells, the breakdown of which leads to the release of an excess amount of this protein compound into the blood plasma. The lack of timely examination and qualified therapy leads to the development of a large number of complications affecting the performance of internal organs.

Diagnosis of hemoglobinuria

The main macroscopic sign of hemoglobinuria is a change in the color and structure of the collected urine. The color of the urine may be dark red, brown, or almost black. When settling, urine is clearly divided into 2 layers: the upper layer is transparent and the lower layer contains an impurity in the form of detritus. Laboratory tests confirming hemoglobinuria are a test with ammonium sulfate, detection of hemosiderin in the sediment, urine examination by electrophoresis or immunoelectrophoresis.

To clarify the overall blood picture, a hemogram is examined. In order to identify complement components or antibodies fixed on the surface of red blood cells, a Coombs test is performed. A study of a coagulogram and biochemical blood parameters (bilirubin, urea, alkaline phosphatase, etc.) is indicated. To assess the state of hematopoiesis, especially in the case of pancytopenia with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, a bone marrow puncture and a myelogram study are required.

Hemoglobinuria must be distinguished from hematuria and the diseases for which it is characteristic (kidney stones, acute glomerulonephritis), porphyria, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia.