Cholecystography - the essence and goals of the study

Diagnostic methods using X-rays to obtain images of human internal organs began to be used in medicine back in the first half of the 20th century. Thanks to the discovery of X-rays in 1895, the science of that time received a powerful tool for studying bone, muscle, connective and other types of tissue, as well as organs and the vascular system without the use of surgery.

Content:

- Cholecystography - the essence and goals of the study

- Gallbladder and bile ducts: anatomy and functioning

- Types of cholecystography

- Indications for the procedure, possible contraindications

- How to prepare for the examination

- The procedure for diagnosing the gallbladder

- Conducting cholegraphy for children

- Features of interpretation of research results

Radiography of the gallbladder using contrast was first experimentally carried out in 1923-1924. Then scientists intravenously injected the sodium salt of tetraiodophenolphthalein into dogs, after which they recorded images of the organ in the photographs. Many theorists and practitioners of medicine further developed this method, making every effort to ensure that the experiment conducted on animals became a full-fledged method for examining the bile ducts and bladder of a person. Ya.G. Dillon, A.A. Lemberg, N.E. Stern, N.F. Mordvinkin and other scientists worked towards studying the possibilities of contrast radiography of the gallbladder and bile ducts.

With the invention in 1946 of a special contrast agent - a diiodinated derivative of a-phenylpropionic acid - the procedure became slightly safer for human health. Bilitrast, as well as the later synthesized Vesipac, Triodan, Cystobil, Telepac, make it possible to increase the percentage of positive cholecystographies: in approximately 50-70% of studies, it is possible to achieve high-quality images of the intrahepatic bile ducts.

For what purposes can the attending physician prescribe the procedure? The examination is carried out for:

- establishing the size and contours of the gallbladder;

- assessing the contractility of the organ walls;

- displaying the size and contours of the bile ducts;

- identifying stones in the bladder and ducts;

- confirmation of the presence of inflammatory or tumor processes.

CHOLECYSTOGRAPHY

CHOLECYSTOGRAPHY

(Greek сhole bile + kystis bladder + grapho write, depict; synonym:

contrast cholecystography, concentration cholecystography

) - an x-ray method for studying the gallbladder, which consists of radiography of it at a certain time after the introduction of special x-ray contrast substances into the body, which are captured from the blood by the liver and released with bile and accumulate in the gallbladder.

Cholecystography was developed in 1923 - 1924 by American surgeons E. Graham and Cole (WH Cole). This method quickly entered clinical practice due to its relative simplicity and safety. Cholecystography allows you to examine the morphology and function of the gallbladder (see), to detect pathological changes in it (developmental anomalies, stones, inflammation, tumor).

Cholecystography is indicated in all cases when it is necessary to determine the condition of the patient’s gallbladder; it can be performed on people of any age. Contraindications are the patient's idiosyncrasy to iodine and acute degenerative liver damage. Coronary insufficiency and severe impairment of liver and kidney function are considered relative contraindications. In recent years, cholecystography has begun to be used less frequently due to the development of ultrasound diagnosis (see) of diseases of the biliary tract, as well as radioisotope cholecystography (see Gallbladder, research methods; Radioisotope cholegraphy).

A radiopaque contrast agent can be given intravenously, by mouth, through a tube into the duodenum, or by enema into the rectum. Currently, the contrast agent is usually administered orally. Organic iodide compounds are used as radiopaque agents. Modern radiopaque agents administered orally, which are used for X. - iopanoic acid (Cholevid, Iopagnost, Telepac), bilimin, etc. - are derivatives of triiodinated benzene.

Rice. 1. The cholecystogram is normal (direct projection) with the patient in an upright position: the shadow of the gallbladder is intense and homogeneous.

No special preparation is required for cholecystography. On the eve of the study day, in the evening after dinner, the patient takes a radiocontrast drug in a dose of 1 g per 20 kg of body weight, washed down with water, fruit juice or sweet tea. The radiopaque substance is not absorbed in the stomach; it is resorbed in the small intestine and, entering the blood, binds to serum albumin. Hepatocytes remove the radiocontrast agent from the blood into the bile in the form of a water-soluble metabolite. The concentration of the drug in bile is low, and therefore the shadow of the bile ducts is usually poorly visible on radiography. In the gallbladder, due to the thickening of bile that occurs in it, the drug is concentrated, and the shadow of the bubble appears on radiographs after 3-4 hours. The image gradually intensifies, reaching a maximum after 15-17 hours (Fig. 1). In children, optimal contrast occurs faster.

Cholecystography is performed on an empty stomach, at 9-10 am the next day after taking the drug. First, they usually take a survey X-ray with the patient in an upright position, and sometimes immediately take targeted images of the gallbladder under fluoroscopy control (separate images are taken while compressing the area of the gallbladder with the tube of an X-ray machine). In case of severe flatulence, they resort to cleansing enemas, but if even after this the accumulation of gas in the colon prevents obtaining a clear image of the gallbladder, then tomography or zonography is performed (see Tomography). The images are used to evaluate the position, shape, size, contours, intensity and structure of the gallbladder shadow. To establish the relationship of the gallbladder with the stomach and duodenum, the patient is given an aqueous suspension of barium sulfate to drink.

Rice. 2. Cholecystogram (direct projection) for a single cholesterol polyp of the gallbladder: the arrow indicates the filling defect caused by the polyp. Rice. 3. Cholecystogram for cholelithiasis (direct projection): multiple clearings in the gallbladder caused by gallstones are visible. Rice. 4. A series of cholecystograms before and after taking a choleretic breakfast are normal: 1 - before taking a choleretic breakfast; 2-7 - during contraction of the gallbladder; 8 - during the period of beginning relaxation of the gallbladder.

Cholecystography may reveal defects (clearances) in the shadow of the gallbladder (Fig. 2, 3), which are caused by a stone (see Gallstone disease), cholesterol polyp (see Cholesterosis) or a tumor. If there are no defects in filling the bladder, the patient is given 20 g of sorbitol dissolved in a glass of water to drink in order to enhance the motility of the gallbladder. For the same purpose, the subject can be given 60 ml of raw egg yolk or another so-called. choleretic breakfast, for example, Boyden's breakfast, consisting of a mixture of two egg yolks and one glass of cream. On photographs after 15-20 minutes, it is often possible to obtain a shadow of the common bile duct (see Bile ducts), which is filled with contrasting bile from the bladder. In addition, radiographs of the contracted gallbladder (20-45 minutes after taking a choleretic breakfast) may reveal small stones or polyps that were not visible on the pictures before the bladder contracted. A series of images allows us to assess the motor function of the gallbladder (Fig. 4). A stronger and faster contraction of the bladder occurs after intravenous or intramuscular administration of cholecystokinin (see), but this is rarely resorted to due to the possibility of abdominal pain and vomiting.

The radiopaque substance, partially passed into the intestines with bile, is excreted with feces, while part of it is reabsorbed and circulates in the hepatic-intestinal circle. Therefore, identifying the shadow of the gallbladder on radiographs is possible the next day. The so-called technique is based on this. saturation during cholecystography. If there is no shadow of the gallbladder on radiographs on the first day of the study, then the patient is given an additional one or two full doses of radiopaque contrast agent during the day and the study is repeated in the morning the next day.

Side effects

weakly expressed during cholecystography. There may be dizziness, nausea, loose stools, and a feeling of pressure in the epigastric region. For symptoms of iodism, antihistamines are prescribed; other side effects disappear without treatment.

Bibliography:

Lindenbraten L. D. Radiology of the liver and biliary tract, M., 1980; Lindenbraten L.D. and Naumov L.B. Methods of X-ray examination of human organs and systems, Tashkent, 1976; Petrova I. S. and Polyak E. 3. X-ray radiological studies of the bile ducts, Kyiv, 1972; GrahamE. A. a. Cole W. N. Roentgenologic examination of the gall-bladder, J. Amer. med. Ass., v.82, p. 613, 1924; Hatfield P. a. Wise RE Radiology of the gallbladder and bile ducts, Baltimore, 1976; Rontgen-diagnostik der Leber und der Gallenwege, hrsg. v. F. Heuck, B. ua, 1976.

L. D. Lindenbraten.

Gallbladder and bile ducts: anatomy and functioning

The gallbladder looks like a small pear-shaped sac. Its main function is the accumulation of bile produced by the liver. Anatomically, the bladder is divided into a bottom, walls or middle part, and a neck, with the bottom having a wider diameter, and then the walls and neck gradually narrowing. The length of the bubble is from 8 to 12 centimeters, width – 3-5 centimeters. The walls of the gallbladder are small in thickness. The color of the organ is dark green or gray-green.

The cystic duct, which looks like a hollow tube, extends from the proximal narrow part - the neck of the bladder. Connecting with the hepatic duct, it forms the common bile duct.

The bladder is located on the visceral side of the liver; it lies in a special hole in the organ. This depression separates the anterior part of the right lobe of the liver and the quadrate lobe. The bottom of the bladder is directed towards the lower edge of the liver, the neck looks towards the hepatic porta. In the place where the body of the bladder meets the neck, there is usually a functional bend, and the neck lies at a certain angle to the body.

The bladder is adjacent to the fossa with its anterior surface, where it connects with the fibrous membrane of the liver. Its surface, directed towards the abdominal cavity, is covered with visceral peritoneum, which passes from the liver to the bladder.

The walls of the gallbladder consist of three layers:

- external serous;

- muscular;

- internal mucosa.

In the area of the peritoneum, the wall is covered with a loose thin connective tissue layer - the subserosal base.

There are three intrahepatic bile ducts:

- general hepatic;

- cystic;

- general bile.

The first of them is located at the porta hepatis and consists of two other hepatic ducts - left and right. Descending in the hepatoduodenal ligament, the common hepatic duct becomes the cystic duct, emanating from the neck of the bladder, forming the common bile duct.

The main function of the gallbladder is to work in close conjunction with the liver. The bile produced by the liver accumulates in the sac until food enters the body. To process fatty and high-calorie foods, the bladder releases a supply of bile into the duodenum, which, together with pancreatic and intestinal enzymes, processes the food bolus. In turn, the bile ducts carry accumulated bile into the intestines.

Types of cholecystography

The main feature by which doctors differentiate the procedure of cholecystography or cholegraphy is the way the contrast agent enters the patient’s body. Based on the route in which the contrast agent is administered, the following types of x-ray examination of the gallbladder are distinguished:

- intravenous cholecystography, when contrast is injected into the body of the subject through the vascular system using a syringe;

- oral procedure: in this case, the subject drinks a special solution containing a contrast agent;

- infusion cholegraphy: a contrast agent is very slowly injected intravenously by drip with a special catheter;

- percutaneous: the method is used if the patient has diagnosed liver dysfunction; contrast is injected by puncture into the gallbladder and ducts.

It should be noted that the latter diagnostic method is practically not used now, as it often causes complications - sepsis, allergies, and in some cases, death.

Indications for the procedure, possible contraindications

Considering that cholecystography directly uses the properties of X-rays, and to obtain an image the patient is necessarily injected with a contrast agent, there must be objective reasons for prescribing such an examination - indications for it.

Among these indications is the need to confirm one of the possible diagnoses:

- suspicion of cholecystitis;

- tumor diseases of the organ;

- dyskinesia;

- stones in the ducts or gallbladder.

Diagnostics can also be prescribed if the patient has certain symptoms:

- pain in the right hypochondrium;

- bitterness in the mouth;

- belching, nausea, vomiting, heaviness in the right side, especially after eating;

- discoloration of feces, accompanied by significant darkening of urine.

As for the prohibitions on prescribing diagnostics, they are mainly associated with the introduction of contrast into the body. Contraindications can be absolute or relative. The former make the procedure completely impossible due to the level of risk for the subject. Cholecystography is contraindicated in patients with:

- liver failure;

- allergies to contrast agents;

- cardiovascular failure;

- acute inflammatory liver diseases.

Relative contraindications require the decision of the attending physician in each specific case - if the need for diagnosis and the benefits of it outweigh the potential harm, the doctor can prescribe cholecystography at his own responsibility.

Relative contraindications are:

- acute cholangitis;

- cirrhosis of the liver

- pregnancy, breastfeeding;

- jaundice.

Gallstone disease: diagnostic and treatment algorithm

AND

Herringbone disease (HSD) is one of the most common diseases. In surgical hospitals, among patients with chronic diseases of the abdominal organs, patients with cholelithiasis occupy first place. In the post-war period in the economically developed countries of Europe and North America, the number of patients with cholelithiasis increased significantly. This is evidenced by the number of operations performed by surgeons - for example, more than 500,000 cholecystectomies are performed annually in the United States alone. In our country, there is also a high incidence of cholelithiasis, and in each subsequent decade the number of patients doubles. This disease is rightly considered the “disease of the century” and the “disease of well-being,” bearing in mind the direct connection of its development with the nature of nutrition.

Over the past three decades, significant progress has been made in addressing the issues of diagnosis and treatment of cholelithiasis, largely due to progress in the development of medical technology and basic sciences. Thanks to these advances in medical practice, effective diagnostic methods have appeared:

Ultrasound (US), computed tomography, magnetic nuclear tomography, direct methods of contrasting the biliary tract.

Along with this, research methods such as oral cholecystography and intravenous cholegraphy have not lost their importance.

Traditional treatment using open cholecystectomy has been supplemented by laparoscopic intervention methods and minimally traumatic operations from a mini-access.

Moreover, doctors now have non-operative treatment methods at their disposal:

drug dissolution and extracorporeal crushing of stones. A wide range of diagnostic and therapeutic methods has led to a revision of the strategy and tactics for cholelithiasis. Naturally, there was a need to optimize the choice of diagnostic tests and treatment method individually for each patient.

The need to rid the patient of cholelithiasis is dictated not only by the emerging attacks of biliary colic, but also by the risk of severe complications (acute cholecystitis, obstructive jaundice, destructive pancreatitis, etc.), which may require urgent surgical intervention, and with a long course of the underlying disease - the development of cancer gallbladder. Therefore, both patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis and its latent form, in which there is always a threat of sudden severe complication of the pathological process, should be treated. Recommendation to a patient of a certain treatment method should be based on an assessment of his physical condition, the nature of the disease, and concomitant changes in the bile ducts (stones, stricture). The information necessary for this can be obtained using a number of instrumental and laboratory studies.

Diagnostics

Ultrasonography

The main method for diagnosing cholelithiasis. Its non-invasiveness, safety and ease of implementation make it possible to examine a large population and resort to repeat research in the next 2-3 days in case of failure or uninformativeness of the initial study. Ultrasound allows you to determine:

the presence of stones in the gall bladder, their number and size, total volume and, importantly, the qualitative composition of the stones;

location, size and shape of the gallbladder, the thickness of its wall and the presence of narrowings in it, the degree of inflammatory and infiltrative changes; the diameter of the hepaticocholedochus and the presence of stones in it. A variant of functional ultrasound using a choleretic breakfast allows one to evaluate the contractile and evacuation functions of the gallbladder. .

Oral cholecystography

A method of X-ray contrast examination of the gallbladder based on oral administration of iodine-containing drugs. Its use is advisable in cases where it is necessary to have accurate data on the functional state of the gallbladder, the radiolucency of stones and the degree of their calcification. This information is extremely important for selecting patients for litholytic therapy and extracorporeal lithotripsy (ECLT). One of the disadvantages of the method is the impossibility of contrasting the bile ducts, the condition of which must be known in all cases without exception when the patient is prescribed treatment.

Intravenous cholegraphy

The method, based on the intravenous administration of a contrast solution, makes it possible to obtain a clear image of not only the gallbladder, but also the extrahepatic bile ducts. This circumstance is extremely important for identifying stones in the bile ducts and determining the degree of their dilatation or narrowing. The detection of even moderate dilatation of the bile ducts on cholangiograms is an indirect sign of impaired bile outflow into the intestine, and in this case, additional research is necessary to identify the cause of biliary hypertension. Intravenous cholegraphy is absolutely indicated in cases where, based on anamnestic and clinical signs, there is a suspicion of concomitant damage to the bile ducts - the presence of stones and stricture in them. To remove these suspicions, you can resort to the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

(ERCP). But compared to this diagnostic method, intravenous cholegraphy is a gentle and less dangerous method, which is not characterized by life-threatening complications.

Hepatobilioscintigraphy

| Surgical removal of the gallbladder is considered as a radical method of treating cholelithiasis. |

It is one of the radioisotope research methods using a gamma camera to record the movement of a radiopharmaceutical through liver cells and bile ducts. Normal indicators of the rate of release of the radiopharmaceutical from liver cells, its movement and evacuation from the bile ducts reliably indicate the absence of disruption of bile outflow into the intestine. If the rate of movement of the radiopharmaceutical through the extrahepatic bile ducts slows down and its release into the lumen of the duodenum is delayed, the presence of stones or strictures should be suspected. To resolve these doubts, radiopaque studies (intravenous cholegraphy, ERCP or intraoperative cholegraphy) are required. The hepatobilioscintigraphy (GBSG) method allows you to assess the functional state of the gallbladder and liver cells

, which is especially important if a patient is suspected of having chronic hepatitis. Low invasiveness, high technology and information content are the basis for the use of GBSG in all cases of uncomplicated cholelithiasis, when the question of prescribing a non-operative or surgical method of treatment to the patient has been positively resolved. Normal indicators of the functional state of the bile ducts according to GBSG data make it possible to select patients for isolated cholecystectomy and not resort to X-ray contrast studies both before and during surgery.

Biochemical blood test

Necessary for assessing the functional state of the liver and characteristics of lipid metabolism. Biochemical analysis determines the level of bilirubin

(direct and indirect fractions),

alanine and aspartate aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, cholesterol and triglycerides

. Normal levels of bilirubin and the activity of major liver enzymes indicate the absence of an active inflammatory process in hepatocytes. The detected high levels of plasma cholesterol and triglycerides indicate a connection between the disease and lipid metabolism disorders. This fact should be given particular importance, since patients with hypercholesterolemia, in addition to the proposed basic treatment, need to undergo hypocholesterolemic therapy aimed at preventing the recurrence of stone formation.

Treatment

As many years of experience have shown, conservative therapy, which is practiced by many outpatient doctors, is ineffective for cholelithiasis. The therapeutic measures they recommend not only do not prevent the occurrence of biliary colic, but can also provoke them due to the migration of stones and blockage of the biliary tract. Moreover, prolonged presence of stones in the gall bladder threatens complications and the development of an inflammatory process, which complicates future surgical intervention and worsens its results. Therefore, in case of cholelithiasis, one should not carry out conservative treatment for years and expect an effect from it. Once a diagnosis has been established, it is necessary to use timely effective treatment methods that will relieve the patient of stones or gall bladder. Observations show that in the early stages of the disease, existing treatment methods, be it lithotripsy or surgery, give better results, treatment is more successful with a low risk of complications and death. The use of one or another method of treating cholelithiasis should not be limited by the age of the patient .

When choosing a treatment method, the determining factor should not be the patient’s age, but his general physical condition and the degree of surgical risk.

Litholytic therapy

The idea of dissolving gallstones with medications is captivating researchers all over the world. It is attractive because the successful use of drugs eliminates the need for surgery, which always carries the risk of an unfavorable outcome. In medical practice, the method of drug dissolution of gallstones appeared in the early 70s, when chenodeoxycholic acid

, and subsequently –

ursodeoxycholic acid

(UDCA). Medicines of this series reduce the cholesterol content in bile by inhibiting its synthesis in the liver and increase the pool of bile acids in bile. As a result, bile loses its lithogenicity and stones dissolve.

The therapeutic effect of enteral use of litholytic drugs is achieved in patients with gallstones consisting primarily of cholesterol. And, as you know, most stones are mixed, also containing bilirubin, proteins and various salts. In this regard, the use of litholysis is possible only in 20% of patients suffering from cholelithiasis. The use of the method is indicated for seriously ill patients with high surgical and anesthetic risk and for patients who refuse surgery or extracorporeal lithotripsy (ECLT). The litholysis method has many contraindications for use; if these are not taken into account, the therapeutic effect is not achieved and complications are possible.

The therapeutic effect when taking litholytic drugs can be expected after 1.5–2 years.

The daily dose of UDCA is 10–15 mg/kg. The best results are observed when limiting the consumption of fatty foods rich in cholesterol. The main disadvantage of the litholysis method is its low efficiency. Even with strict selection of patients, it is possible to dissolve stones or reduce their size in no more than 60% of them, and this effect is achieved with small pure cholesterol stones. After stopping medication, a high percentage of disease relapse was observed. Insufficiently high efficiency limits the use of litholytic therapy as an independent method of treating cholelithiasis. It is more widely used in combination with other methods and, in particular, with remote crushing of stones.

Extracorporeal lithotripsy

The method of non-invasive crushing of gall bladder stones entered medical practice in 1985. The advent of this method gave rise to doctors' hope for the possibility of its widespread use, which would allow many patients to avoid surgery. However, the first observations showed that not every patient can be recommended for this treatment procedure and not in all cases a positive result is achieved. To obtain a therapeutic effect, strict selection of patients is necessary. Experience shows that the effectiveness of extracorporeal lithotripsy (ECLT) depends on the properties of the stones

, determining the success of their fragmentation and elimination, as well as

from the functional state of the gallbladder

, which determines the frequency of complications and

side effects of the elimination period and early relapses of stone formation

.

The selection criteria for patients with cholecystolithiasis (with symptomatic and asymptomatic forms of the disease) for ECLT are: single and few (2–4) stones occupying less than 1/2 of the gallbladder volume; preserved contractile-evacuation function of the gallbladder. The success of treatment largely depends on the presence of calcium salts in the stones and the degree of their calcification. Good treatment results are achieved in patients with echo-permeable and echo-tight (not containing calcium salts) radiolucent stones; as their echo-proofness and echo-density with signs of radiopacity increase, the efficiency of crushing decreases.

Contraindications to the use of ECLT are: multiple cholecystolithiasis, occupying more than 1/2 of the gallbladder volume; calcined stones; decreased contractile-evacuation function of the gallbladder and “disabled” gallbladder; bile duct stones and biliary obstruction; impossibility of performing enteral litholysis after crushing stones (gastroduodenal ulcer, allergy); pregnancy.

The results of lithotripsy are judged after 3–18 months

when the gallbladder is freed from stone fragments. To speed up the elimination process and reduce the size of fragments, patients are prescribed oral litholytic therapy. In the immediate and long-term periods, the process of elimination of fragments can give rise to complications in the form of attacks of biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, obstructive jaundice and acute pancreatitis. It should be noted that these complications occur rarely. With strict selection of patients, good treatment results (complete release of the gallbladder from stones) are observed in 65–70% of patients. Unsatisfactory results of ECLT, when fragments do not leave the gallbladder or, on the contrary, increase in size, are associated either with an incorrect assessment of the function of the gallbladder or with the qualitative composition of the stones. After successful lithotripsy, relapse of stone formation is possible, observed in 20–23% of patients who have undergone this procedure (most of them have lipid metabolism disorders). A measure to prevent relapse of the disease in this category of patients is corrective cholesterol-lowering therapy.

Non-operative methods of treatment have one significant drawback - the non-pathogenicity of therapy. One cannot expect good treatment results when using them in the long term, since if it is impossible to influence all links in the pathogenesis of the disease, the gallbladder, the organ that forms stones, still remains. That is why surgical removal of the gallbladder is considered as a radical method of treating cholelithiasis

, relieving the patient from biliary colic and dangerous complications. Currently, medical institutions use three methods of gallbladder removal: laparoscopic, surgical through minimal surgical access, and through standard laparotomy.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

The emergence of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LCE) in medical practice was a new milestone in the development of cholelithiasis surgery. In just over 10 years of existence, it has gained widespread recognition and has been further improved. Up to 70–80% of cholecystectomies began to be performed using the endoscopic method.

Indications for LCE

include symptomatic uncomplicated cholelithiasis, an asymptomatic form of the disease and cholesterosis of the gallbladder. Improvements in the technology of endoscopic surgery have made it possible to expand the indications for intervention for combined lesions of the bile ducts. Contraindications to this operation include a dense inflammatory infiltrate in the area of the gallbladder neck and hepatoduodenal ligament, pregnancy, previous laparotomies, obesity, liver cirrhosis, intrahepatic location of the gallbladder, obstructive jaundice and acute pancreatitis. Some authors consider these contraindications, with the exception of the first two, to be relative and at the same time emphasize that the success of the operation is largely determined by the level of training of the surgeon and the technical equipment of the operating room. However, these contraindications cannot be underestimated, since in these situations there is a risk of developing intraoperative complications and, in addition, there is a need for conversion (transition to laparotomy), which lengthens the operation time by 2-3 times.

The LCE operation is usually performed under general anesthesia, while achieving deep relaxation of the abdominal wall. The main stages of endoscopic surgery are:

creation of pneumoperitoneum, introduction of trocars and instruments, revision of the abdominal cavity, isolation of the gallbladder from adhesions, cystic duct and cystic artery, followed by their clipping and intersection; isolating the gallbladder from the liver bed and removing it from the abdominal cavity (sometimes using a container) and installing a control drainage in the subhepatic space. To insert trocars into the abdominal cavity, an arcuate incision 1.5–2 cm long is made above or below the navel and three incisions 5–6 mm long in the right hypochondrium.

Minor trauma during LCE surgery and gentle instrumental technique ensure an easy course of the postoperative period, a short stay for the patient in the hospital (3–5 days) and a reduction in the recovery time (2.5–3 weeks). These factors determine the low percentage of postoperative complications from the surgical wound, abdominal cavity and cardiopulmonary system. The listed advantages of LCE make it socially significant and promising in the treatment of cholelithiasis.

Along with the undeniable advantages, LCE surgery is fraught with the risk of developing serious complications: bleeding into the abdominal cavity, intersection of the common bile duct, injury to internal organs, bile leakage into the abdominal cavity, purulent processes in the intervention areas. The causes of their occurrence are most often adhesive and inflammatory processes in the hepatoduodenal zone; violation of surgical technique and refusal to timely transition to wide laparotomy. During LCE surgery, postoperative mortality is low, it ranges from 0.5 to 1.5%.

Cholecystectomy from mini-laparotomy access

In our country, priority in the development of cholecystectomy technology from a small surgical approach belongs to I.D. Prudkov and his followers.

This method of cholecystectomy operation consists of an open small surgical approach with elements of endosurgery.

The operation is carried out using a set of instruments, including a ring retractor, articulated retractors-mirrors (changing their geometry), a lighting device and electrocoagulators.

To perform the operation, a vertical transrectal incision 4–5 cm long is made from a mini-access in the right hypochondrium. Mirror retractors create a large surgical space that allows you to operate at a depth of 5–20 cm, visually monitor the progress of the operation and freely manipulate instruments. By changing the position of the mirror retractors and thereby increasing the surgical space in the area of “interest”, it is possible to perform not only an isolated cholecystectomy, but also to expand the intervention: perform choledocholithotomy, choledochoscopy, and form a supraduodenal choledochoduodenoanastomosis.

The use of mini-laparotomy access for cholecystectomy is advisable in cases where there are contraindications to laparoscopic intervention. The technology of this operation makes it possible to remove the gallbladder in the presence of inflammatory infiltration and adhesions in the area of the hepatoduodenal ligament; with previous laparotomies, when fusion of the abdominal organs with the abdominal wall can be expected; with obesity and intrahepatic location of the gallbladder. Mini-access is preferable in patients with concomitant diseases of the cardiac and pulmonary systems, in whom it is undesirable to create tension pneumoperitoneum.

Mini-access cholecystectomy surgery is not an alternative to the laparoscopic method. In many medical parameters, these methods of operation do not differ significantly from each other. However, operations from a mini-access are characterized by a slightly increased morbidity due to the length of the abdominal wall incision and the insertion of instruments and tampons into the abdominal cavity. The undoubted advantages of cholecystectomy from a minimal surgical approach are: the similarity of the operating technique and techniques with open laparotomy and visual control of the stages of the operation, which reduces the risk of iatrogenic complications, allows the surgeon to easily overcome the psychological barrier and quickly move to open laparotomy if technical difficulties arise. In addition, the cost of a mini-access operation is 2.5–3 times less than a laparoscopic operation. The listed advantages of mini-access cholecystectomy using domestic instruments make it attractive for surgeons. Currently, in many medical institutions in our country, this operation has replaced the open method of surgical intervention.

Cholecystectomy from open laparotomy access

Removal of the gallbladder from a standard wide laparotomy approach falls into the category of traumatic interventions with an increased risk of complications. Despite this disadvantage of wide laparotomy, the need for its use remains in complicated cases of cholelithiasis, when intervention on the extrahepatic bile ducts is required, as well as in surgery for acute cholecystitis. A forced transition to wide laparotomy occurs during laparoscopic and mini-access operations if technical difficulties or iatrogenic complications arise during surgery.

So, of the existing methods of treating cholelithiasis, the most effective is surgical - removal of the gallbladder.

During planned operations in patients with uncomplicated cholelithiasis, postoperative mortality does not exceed 0.5%. It is important to identify indications for surgery in a timely manner, without waiting for the development of complicated forms of the disease.

How to prepare for the examination

Doctors, when prescribing cholegraphy, emphasize that the quality of diagnostic results directly depends on how responsibly the subject treats compliance with the preparation rules.

The patient preparation algorithm includes a mandatory slag-free diet. Five days before the appointed date, it is necessary to exclude from the diet all foods that increase gas formation in the intestines:

- bread, especially black bread, pastries;

- legumes;

- carbonated and alcoholic drinks;

- milk and dairy products;

- fatty meat and fish;

- vegetables and fruits rich in coarse fiber.

Within 24 hours, a doctor can test a person for sensitivity to bilitrast. To do this, he is injected intravenously with 1 milliliter of the drug, diluted with 10 milliliters of saline.

On the day preceding the examination, it is also necessary to comply with some menu requirements. In the first half of the day, it is allowed to eat regular food, with the exception of the above products. This is necessary so that the bile that has already accumulated in the bladder comes out of it. Lunch, snacks and dinner should be as light and low-fat as possible so as not to cause bladder contraction.

In the morning before the procedure, eating and drinking is prohibited - cholecystography is carried out strictly on an empty stomach.

In preparation for oral cholecystography, the patient must drink the contrast drug 12-14 hours before. The dosage of the substance is calculated by the attending physician, focusing on the weight of the patient. After consuming the drug, a person needs to lie on his right side so that the liquid is better absorbed. Before going to bed, a cleansing enema is given, and in the morning before cholecystography it can be repeated. The contrast agent may cause nausea and loose stools. After this, the subject is also prohibited from drinking, chewing gum and smoking.

The procedure for diagnosing the gallbladder

Before the examination, the diagnostician takes a survey x-ray of the right hypochondrium to assess the degree of preparedness of the digestive organs. Also, the image taken will help identify shadow formations that may indicate the presence of stones, gas, or lime deposits in the bile ducts.

The procedure algorithm consists of two stages: first, an image of the filled organ is recorded, then pictures of the bladder are taken after emptying.

To take contrast images, the patient is placed on a special couch, first in the “prone” position. Next, the doctor asks the patient to move to the left side, stand up straight, while paying attention to the separation of the contents of the bladder or the presence of movable filling defects.

The shadow of the contrasted gallbladder is displayed in the center of the screen, and in the absence of a contrast image - in the area of its projection. The projection point of the organ is located at the intersection of the outer edge of the right rectus abdominis muscle and the arch of the ribs. Given the differences in size and position of the gallbladder and liver, the location of the projection may differ.

In the photographs, the bubble may be reduced or enlarged, deformed, wrinkled, located in the upper part of the right hypochondrium, or extending into the pelvic cavity. The organ may also deviate to the left or right, with its shadow cast on the right kidney or vertebrae.

If the subject has a blockage of the gallbladder (cystic duct obstruction), its shadow will not be visualized on the image. In addition, the lack of contrast in the organ can be explained by functional disorders, for example, deterioration of the excretory function of the liver.

The second stage of diagnosis begins after the patient is given choleretic food or medicine - this is how the phase of contraction and emptying of the bladder begins. During this stage, the doctor can evaluate the so-called evacuation function of the organ, and as the contrasting bile disappears from it, determine the size and location of stones, scars or neoplasms in the walls.

The common bile duct is visible on images taken after 15 and 30 minutes. If the emptying function is slow, the last image recording is made after 60 minutes.

Propaedeutics of radiation methods for examining the gallbladder

The leading method for diagnosing pathological changes in the gallbladder (GB) is ultrasound examination (US).

Ultrasonography

Its undoubted advantages are non-invasiveness, the ability to quickly and portablely conduct research; absence of ionizing radiation and the need for intravenous administration of contrast agents; independence from the physiological state of the gastrointestinal tract and hepatobiliary system [1–3].

Features of gallbladder syntopy - the proximity of its posterior wall in the body and fundus to the right parts of the large intestine and duodenal bulb - dictate the need to prepare patients for ultrasound examination in order to reduce pneumatization of the corresponding parts of the digestive tract. This requires at least a 6-hour fast on the eve of the diagnostic procedure, and it is optimal to conduct the study on an empty stomach after a night's sleep. Such conditions are also required for the most detailed visualization of the structure of the gallbladder wall and its contents, since it is a hollow organ filled with bile and capable of contracting in response to humoral stimulation during food intake, which leads to a decrease in its size, a sharp thickening of the walls and the inability to detail intraluminal changes [2, 3].

The anatomical structure of the gallbladder is simple. It consists of a narrow neck connecting to the cystic duct, a bladder body with almost parallel walls, and a dome-shaped bottom. At the junction of the neck and the cystic duct, the wall often forms a pouch (or diverticulum) of Hartmann, in which stones can accumulate, blocking the exit of the cystic bile [3–5] (Fig. 1).

To conduct an ultrasound examination of the gallbladder, the scanner sensor (usually with a frequency of 3.5 MHz) is placed in the right hypochondrium of the subject - the site of the anatomical projection. Visualization of the organ can be improved by placing the patient on the left side, which allows the intestinal loops to be somewhat pushed to the left; the same purpose is served by conducting the study while holding the breath with a deep breath. Visualization of the gallbladder through the intercostal spaces is the most consistent, but the least informative and is used mainly in urgent situations in unprepared patients. To better assess the nature of intravesical changes (the presence of small stones, identifying their mobility), it is possible to conduct an examination in a vertical position or with the body tilted forward [2–5].

In the diagnosis of cholelithiasis (GSD), ultrasound scanning rightfully occupies a leading position. The sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting gallstones exceeds 95%, which look like hyperechoic structures with an acoustic shadow [1, 5] (Fig. 2).

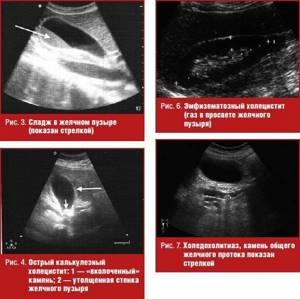

In the vast majority of cases, the stones are mobile, but can be fixed to the wall or motionless in the neck of the bladder. Other foreign bodies that mimic cholelithiasis may be blood or pus clots or parasites. Gallbladder polyps are immobile or have limited mobility if they have a pedicle, are always connected to the wall and, as a rule, do not give an acoustic shadow; usually their size does not exceed 5 mm. As a rule, against the background of a long absence of contractions of the bladder, it is possible to visualize the stratification of bile into two components with a clear interface, one of which is anechoic and occupies the upper parts of the bladder in relation to the horizontal plane, the other is more dense, located below. This phenomenon, called stagnation of bile, or sludge, occurs due to the presence of cholesterol and calcium bilirubinate crystals in it and their ability to reversibly form large aggregates (Fig. 3) .

The most common complication of cholelithiasis is acute cholecystitis, the cause of which is almost always a violation of the outflow of bile from the gallbladder. The main ultrasound signs of this pathology are:

- the presence of stones in the lumen of the bladder (the most typical finding is an “impacted” stone in the neck) - Fig. 4;

- thickening of the wall more than 3 mm with the appearance of heterogeneity of its structure, delamination (Fig. 4);

- an increase in the transverse size of the bladder by more than 4 cm; detection of the greatest pain at the site of ultrasound projection of the gallbladder (ultrasound Murphy’s symptom), which may not be detected in gangrenous cholecystitis [3, 5] (Fig. 4).

The combination of these symptoms with the detection of fluid accumulation near the bladder, especially in combination with the identification of a wall defect, indicates its perforation and, possibly, the formation of a peripysical abscess (Fig. 5). The detection of ultrasound signs of gas accumulation in the lumen of the bladder against the background of other signs of acute inflammation indicates such a severe pathology as emphysematous cholecystitis caused by gas-forming anaerobic flora [3, 5] (Fig. 6).

Another complication of cholelithiasis, manifested by a violation of the passage of bile, is choledocholithiasis. Violation of the outflow of bile along the common bile duct causes its expansion of more than 7 mm, expansion of the intrahepatic bile ducts (more than 40% of the diameter of the adjacent branch of the portal vein) (Fig. 7). Indisputable evidence of choledocholithiasis is the detection of stones, which are most often localized in the distal part of the common bile duct, but can be visualized only in 70–80% of cases [1, 4, 5].

Dilation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts is also observed with such a complication of cholelithiasis as Mirizzi syndrome, which consists of obstruction of the common bile duct as a result of the volumetric effect of the inflammatory reaction of tissues to a stone located in the neck of the bladder or cystic duct, with a low confluence it in the common bile duct (Fig.

Often the formation of stones in the gallbladder is accompanied by benign changes in its walls, one of the main ones being a violation of cholesterol metabolism. These changes are called hyperplastic cholecystopathy. One of its variants - cholesterol dystrophy is manifested by such ultrasound signs as the detection in the wall of the bladder of hyperechoic deposits no larger than 1 mm in size, which do not give an acoustic shadow, but are accompanied by a reverberation effect (the bubble vaguely resembles a strawberry), which are lipid deposits (Fig. 9) . More pronounced changes in the wall, called adenomyomatosis, are manifested in its thickening, the formation of intramural diverticula (Aschoff-Rokitansky sinuses), containing hyperechoic cholesterol deposits with a reverberation effect (“comet tail”) and microliths that give an acoustic shadow (Fig. 9). Hyperplastic cholecystopathy can affect both the entire bladder and part of its wall [2, 5].

It is known that removal of the gallbladder for cholelithiasis does not relieve patients from metabolic disorders, including hepatocyte dyscholia, which persists after surgery [6]. The loss of the physiological role of the gallbladder, namely the concentration of bile in the liver during the interdigestive period and its release into the duodenum during meals, is accompanied by a violation of the passage of bile into the intestine and indigestion [6, 7].

Changes in the chemical composition and volume of bile, its chaotic entry into the duodenum after cholecystectomy (CE) disrupt the digestion and absorption of fat and other lipid substances, reduce the bactericidal nature of duodenal contents, which leads to microbial contamination and impaired motility of the duodenum, the development of bacterial overgrowth syndrome in the intestine (especially in the ileum), disruption of the enterohepatic circulation and decreased synthesis of bile acids in the liver [6]. As a consequence, a syndrome of impaired digestion, the symptoms of which are often mistakenly interpreted as postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS), is associated by surgeons primarily with mechanical obstacles to bile outflow that were not recognized before surgery or were not eliminated during cholecystectomy (stones left or emerging again in the common bile duct, stenosis of the papilla of Vater and etc.) [6].

When preparing for a cholecystectomy operation, much attention is always paid to diagnosing mechanical obstacles to bile outflow into the duodenum. The situation is completely different with preoperative verification of extrahepatic biliary dysfunctions. The absence of indirect signs of functional disorders of the sphincter of Oddi in the form of dilation of the common bile duct during ultrasound, increased liver enzymes, pain attacks, etc. does not at all exclude dysfunction of the papilla of Vater, which forms long before the patient’s admission. According to our data, in 45% of patients with cholelithiasis, radionuclide hepatobilis scintigraphy (GBSG) reveals functional disorders in the transport of radiopharmaceuticals from the common bile duct to the duodenum, which do not require retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic correction.

In some cases, radionuclide methods are simply no alternative due to the strict specificity of the inclusion of radiopharmaceuticals (RP) in various metabolic processes (GBSG). The functional state of the hepatobiliary system in any pathology of the hepatobiliary system, including cholelithiasis, is studied using standard GBSG.

Hepatobiliscintigraphy

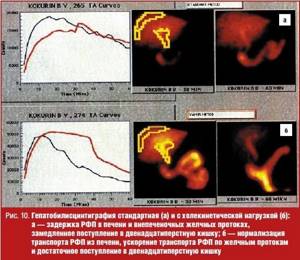

GBSG allows you to objectively evaluate the most important processes from the standpoint of the functioning of the digestive transport conveyor: bile synthetic and bile excretory functions of the liver, as well as the transport of bile into the duodenum. The method is based on recording the passage of short-lived radionuclides Tc-99m + bromezide through the biliary tract.

The study is carried out on an empty stomach, in a horizontal position of the patient after the administration of 3 mKM Tc-99m + bromezide intravenously. The duration of the procedure is 60 minutes. As a choleretic breakfast, patients take chicken egg yolks or 200 ml of 10% cream 30 minutes from the start of the study.

Normal indicators of GBSG are considered:

1) the half-life (T1/2) of the radiopharmaceutical (RP) from the liver is less than 35 minutes; 2) the half-life (T1/2) of radiopharmaceuticals from the common bile duct is less than 50 minutes; 3) the time of receipt of radiopharmaceuticals into the duodenum is less than 40 minutes; 4) adequate supply of radiopharmaceuticals to the intestine is the predominance of radiopharmaceutical activity in the duodenum compared to that in the common bile duct by the end of the study.

The generally accepted standard method of radioisotope research with a choleretic breakfast does not always make it possible to specify the nature of functional changes in the bile outflow. This is explained by the fact that the food load exerts its effect both by activating the entry of cholecystokinin (CC) into the bloodstream upon irritation of I-cells of the duodenal mucosa and intramural nerve plexus [8]. The activity of digestive enzymes and the sensitivity of the sphincter apparatus of the biliary tract to intestinal hormones is variable and in practice difficult to determine [9]. The tone of intramural nerve fibers depends on the physiological activity of the organs of the upper digestive tract [10, 11].

In this regard, in the radionuclide diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary dysfunction (IBD), intravenous administration of the hormone cholecystokinin is often used, but the relaxing effect of this drug depends on the state of the central nervous system, the hormonal background of the patient and is disrupted in case of cholesterosis of the gallbladder, since the localization of receptors for cholecystokinin coincides with the sites of deposits cholesterol esters in the bladder wall and bile ducts, which makes it difficult to accurately determine the dose of the administered hormone [8, 10].

To clarify the nature of bile outflow disorders along the common bile duct in the Faculty Surgery Clinic named after. S. I. Spasokukotsky Russian National Research Medical University named after. N.I. Pirogov on the basis of the First City Hospital performs GBSG with amino acid cholekinetic test (GBSG-ACT) and GBSG with Buscopan® test (RF patent No. 2166333).

GBSG with amino acid cholekinetic test

The study is carried out on an empty stomach. 30 minutes after the administration of the radiopharmaceutical and the start of the study, a solution of amino acids Vamin-14 or Freamin, which does not contain glucose and electrolytes, is injected into a peripheral vein. We consider the last condition to be very important, since the hyperglycemia that occurs during glucose infusion completely or partially inhibits the secretion of cholecystokinin [8]. The dose of the drug was chosen at the rate of 1.5–2 ml/kg body weight (80–130 ml). The duration of the infusion is 5–7 minutes, since the administration of an amino acid solution for more than 10 minutes (regardless of the dose) does not lead to an increase in the release of endogenous cholecystokinin, but, on the contrary, reduces the incretion of the hormone [9]. IAP and the cause of delayed excretion of the radiopharmaceutical by hepatocytes are assessed based on the differences in the parameters of standard GBSG and GBSG-ACT (Fig. 10).

GBSG using hyoscine butyl bromide

Hyoscine butyl bromide (Buscopan®) is a derivative of the tertiary ammonium compound hyoscine. Hyoscine is an alkaloid present in plants of the genus Duboisia. It is chemically processed by adding a butyl group to produce a quaternary ammonium structure. This modification forms a molecule that still has anticholinergic properties comparable to those of hyoscine.

But unlike hyoscine, quaternary ammonium compounds such as hyoscine butyl bromide limit systemic absorption and significantly reduce the number of adverse reactions. Hyoscine butyl bromide is an anticholinergic drug with a high degree of affinity for muscarinic receptors located on the smooth muscle cells of the gastrointestinal tract, causing an antispasmodic effect. In addition, the drug binds to nicotinic receptors, which determines the effect of blocking the nerve ganglia, which determines its antisecretory effect.

The technical side of the study differs little from the above-mentioned AChT test. At the end of standard hepatobiliscintigraphy, instead of infusion of an amino acid solution, the patient takes 20 mg of hyoscine butyl bromide per os. After 20 minutes, the data is re-recorded and processed (Fig. 11). Thus, the use of the Buscopan® test reduces diagnostic time for the doctor and simplifies the diagnostic procedure for the patient.

GBSG with the Buscopan® test has proven itself to be most effective in the study of patients after cholecystectomy (Fig. 12).

The leading factors of liver dysfunction after cholecystectomy are the presence and duration of dyskinesia of the sphincter apparatus of the biliary tract. In patients, paradoxical spasm of the sphincter of Oddi significantly predominates as the cause of delay of radiopharmaceuticals in the common bile duct. Functional disorders of bile outflow are caused by cholesterosis of the biliary tract, in particular the sphincter of Oddi (Fig. 13, 14).

X-ray methods

X-ray methods for studying the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts are practically not used today, so we provide a brief description of them as a historical reference.

Survey radiography

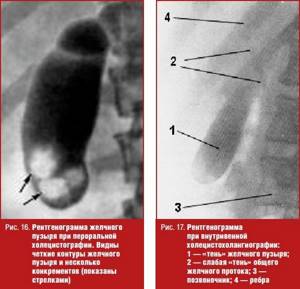

Plain radiography of the abdominal cavity is performed much less frequently than ultrasound due to radiation exposure. But, nevertheless, it was a fairly informative method for diagnosing cholelithiasis. On the x-ray you can see the presence, location and number of x-ray stones containing calcium salts (Fig. 15).

Oral cholecystography

Oral cholecystography is performed if X-ray negative (cholesterol) stones are suspected. The method is based on absorption in the gastrointestinal tract and excretion of the contrast agent with bile (Fig. 16).

If absorption in the intestine is impaired, the excretory function of the liver is reduced, the cystic duct is blocked by a stone, etc., oral cholecystography may be negative, i.e., the shadow of the gallbladder is not detected on it.

Intravenous cholecystography

Intravenous cholecystography is performed if the result of the oral radiocontrast method is negative. Using this technique, it is possible to contrast the gallbladder in 80–90% of cases (Fig. 17).

Computed tomography and magnetic nuclear (magnetic resonance) imaging

The shortcomings of classical X-ray studies of the gallbladder are successfully compensated by computed tomography (CT) and magnetic nuclear tomography (magnetic resonance imaging, MRI). In calculous cholesterosis, stones are visualized as shadows of a homogeneous structure (cholesterol stones) (Fig. 18) or are represented by heterogeneous shadows with alternating areas of mixed stones - a cholesterol core with a calcium-bilirubin shell (Fig. 19).

Computed tomography and magnetic nuclear tomography make it possible to suspect cholelithiasis in patients examined for other pathologies of the abdominal organs, since a description of the image of the gallbladder is a mandatory component of the protocol for these studies.

Literature

- Practical guide to ultrasound diagnostics. Ed. V.V. Mitkova. M.: Vidar-M, 2003. T. 1. 720 p.

- Brant WE, Helms CA Fundamentals of Diagnostic Radiology, 2nd ed. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, p. 836–841.

- Kurtz AB, Middleton WD Ultrasound: The Requisites. Philadeiphia, Hanley & Belfus, 1996, p. 35–71.

- Parulekar SG Transabdominal sonography of bile ducts // Ultrasound Q. 2002, (18) 3: 187–202.

- Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW (eds). Diagnostic Ultrasound, 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 1998, p. 172–195.

- Savelyev V. S., Petukhov V. A. Cholelithiasis and indigestion syndrome. M.: BORGES, 2010. 258 p.

- Savelyev V. S., Petukhov V. A., Boldin B. V. Cholesterosis of the gallbladder. M.: VEDI, 2002., 176 p.

- Vysotskaya R. A. Prostaglandins and gastrointestinal hormones in chronic liver diseases. Diss. doc. biol. Sci. M., 1992, 340 p.

- Houda R., Tooli J., Dodds WJ Effect of enteric hormons on sphincter of Oddi and gastrointestinal myoelectric activity in fasted conscious opossums // Gastroenterol. 1983, vol. 84, p. 1–9.

- Weechsler-JG Bedeutung der Gallenblase in der Regulation des duodenogastralen Refluxes // Z-Gastroenterol. 1987, Aug. 25, Suppl 3: p. 15–21.

- Petukhov V. A. Lipid distress syndrome. Ed. V. S. Savelyeva, M.: MAX PRESS, 2010. 544 p.

V. A. Petukhov*, 1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor D. A. Churikov**, Candidate of Medical Sciences

* GBOU VPO RNIMU im. N. I. Pirogova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow ** State Clinical Hospital No. 1 named after. N. I. Pirogova, Moscow

1 Contact information