A variety of coccal flora lives on the skin and mucous membranes of every person. Gonococci, pneumococci and others are pathogenic. Streptococci and staphylococci, which represent the majority of this flora, are considered opportunistic. These microorganisms are present in small quantities and in their normal states are not harmful to human microflora. However, due to various unfavorable factors, the number of streptococci and other microorganisms is rapidly growing and provokes an inflammatory process.

Composition of normal vaginal microflora

The gold standard for diagnosis in gynecology is the examination of a smear taken from the posterior vaginal vault and cervical canal. Normally the following can be found:

- 1Döderlein acidophilus bacilli (lactobacteria). Normally, their number should be at least 85-95% of the entire flora or 106-108 copies in the sample.

- 2Bifidobacteria (about 10%).

- 3Peptostreptococci, eubacteria, prevotella, bacteroides, fusobacteria and other anaerobic bacteria (5%).

- 4Other cocci and fungi (in small quantities).

- 5Epithelium (not much, its quantity depends on the phase of the menstrual cycle).

- 6Leukocytes (up to 10 cells).

This ratio of microorganisms can maintain a slightly acidic environment for a long time, allows you to fight pathogenic bacteria, provides natural hydration and local immunity. The state of the vaginal microflora is assessed using laboratory methods and has its own conditional classification.

Degrees of vaginal cleanliness

The concept of degrees of purity was introduced in order to promptly identify women at risk for inflammatory diseases of the genital organs (vaginitis, cervicitis, endometritis, and so on). You can read more about this in our other article (follow the internal link). They are identified based on the results of a simple smear for flora and GN:

- 1First degree (second name - normocenosis): acidic environment. Normal number of lactobacilli, few epithelial cells, no cocci. It is rare, usually observed immediately after treatment or the use of antibiotics.

- 2Second degree: acidic environment. The number of lactobacilli is slightly reduced, leukocytes (up to 10) and small diplococci appear. The number of cocci is insignificant (one or two pluses).

- 3Third degree: the environment becomes slightly acidic or alkaline. The number of Doderlein rods is significantly lower than normal, there is a lot of epithelium, leukocytes 10-30, coccal or bacillary flora predominates, fungal mycelium can be detected. This condition is called dysbiosis (dysbacteriosis). Such women need to be monitored and receive timely treatment.

- 4Fourth degree: alkaline environment. Lactobacilli may be completely absent, a large number of epithelial cells, leukocytes (above normal), many cocci or other pathogenic bacteria. This degree corresponds to vaginitis, therefore, treatment of the woman is mandatory.

As the pH shifts toward the alkaline side, the quality and quantity of flora changes. The level of acidophilus bacilli gradually decreases, cocci multiply, then fungi and other bacteria join.

An alkaline environment is detrimental to Doderlein's bacilli, which leads to the development of vaginal dysbiosis.

It is worth noting that the following microorganisms can be found in normal smears: hemolytic streptococcus, aureus, epidermal and saprophytic staphylococcus, peptococci, micrococci, green streptococcus and others. All of them in small quantities do not pose a threat to health and are opportunistic representatives of the vaginal flora.

With 3-4 degrees of vaginal cleanliness, the following types of cocci can most often be detected:

- 1Streptococci. As mentioned above, these microorganisms are allowed in small quantities, but their increased proliferation leads to the occurrence of an inflammatory process - vaginitis.

- 2Enterococcus fecal. Often found in the intestines, if it enters the genitourinary tract it can cause cystitis or colpitis. Detection of it in large quantities in smears indicates a violation of the rules of intimate hygiene, including during sex.

- 3Staphylococcus is an opportunistic microorganism that normally lives on the skin. With increased reproduction, it can cause serious inflammation with damage to the external and internal genital organs.

- 4Diplococcus occurs in vaginal dysbiosis with disruption of the normal composition of the microflora of the mucous membrane.

There are other cocci, they usually cause nonspecific colpitis.

Important! If Staphylococcus aureus is detected in a gynecological smear, then there is a possibility of its detection on the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract (oropharynx, nasal cavity).

Vaginitis caused by opportunistic microflora: recommendations for medical practitioners

About the author:

Pustotina Olga Anatolyevna, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine, Faculty of Education and Science of the People's Republic of Russia, RUDN Address: 117198 Moscow, st. Miklouho-Maklaya 6, phone 8, email Pustotina Olga Anatolievna, Doctor of Medicine, Professor of The department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Health, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia. Address: 117198 Moscow, Mikluho-Maklaya str, 6. Phone 8(495)7873827

Normal microflora of female genital organs

The natural microflora of the vagina and external genitalia is represented by a wide range of saprophytic and opportunistic microorganisms (OPM). From the vagina of healthy women of reproductive age, streptococci, staphylococci, peptobasteroptococci, bifidobacteria, corinatics, enterococci, intestinal stick, Klebciella, Proteus, fuzobacteria, guard-reellla, atopobium, mycoplasmas, bacteroids, and mushrooms of the genus of the genus SAPSIS1A1A , extensor, Vilonella, etc. But they are contained in small quantities, not exceeding 103-104 CFU per 1 ml of secretions. The main representatives of the vaginal microflora are lactic acid anaerobic bacteria belonging to the lactobacilli family, which significantly dominate the UPM and amount to 107-109 CFU/ml [1-3].

Lactobacilli maintain the constancy of the composition of the vaginal ecosystem and play an important role in the body’s nonspecific defense against infectious aggression. Covering the mucous membrane of the vagina and cervix, they produce humoral immune defense factors, preventing the adhesion of other microorganisms to it. In addition, lactobacilli have antagonistic properties to some representatives of the intestinal flora - Escherichia coli, Proteus, Klebsiella, protecting the vagina from contamination by them. In the process of their vital activity, they break down glycogen contained in the vaginal mucosa with the formation of lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide, creating an environment with a low acidity level (pH 3.5-4.5), unfavorable for the proliferation of other microorganisms [1-3].

Thus, in the vagina of healthy women of reproductive age, the total number of bacteria is 105-106 CFU/ml of secretions, 95% of which are lactobacilli and only 5% are formed by representatives of other types of aerobic and anaerobic UPM.

Vaginitis caused by UPM

Vaginitis can be inflammatory or non-inflammatory. Inflammatory vaginitis, depending on the type of pathogen, is divided into nonspecific and specific. Specific ones include trichomonas, chlamydial, gonococcal and fungal vaginitis (vaginal candidiasis); if any other UPM is detected, vaginitis is nonspecific. Non-inflammatory vaginitis is called bacterial vaginosis. Bacterial vaginosis, nonspecific vaginitis and vaginal candidiasis include vaginitis caused by UPM.

Bacterial vaginosis is a non-inflammatory disease (dysbacteriosis) of the vagina, characterized by a sharp decrease in the number of lactic acid bacteria and an excessively high concentration of obligate and facultative anaerobic UPM. The content of lactobacilli is less than 106 CFU/ml, and atypical forms that do not produce hydrogen peroxide predominate among them. As a result of a decrease in the concentration of hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid, the pH level of the vaginal contents increases >4.5 and conditions are created for the growth of UPM. Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae are found in large quantities in synergy with strict anaerobes: Prevotella, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Mobilluncus, etc. In addition, aerobic microbes (Streptococcus, Staphilococcus, Escherichia coli, Proteus, Klebsiella, etc.) and mycoplasma (Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealiticum, Ureaplasma parvo). the total number of bacteria in the vagina increases significantly and reaches 108-1011 CFU/ml [4-6].

Bacterial vaginosis occurs in every second woman who complains of pathological discharge from the genital tract. Its frequency is 2 times higher than vaginal candidiasis and 5-10 times higher than chlamydial, trichomonas and gonococcal vaginitis combined [1-3].

Bacterial vaginosis is not a sexually transmitted infection (STI), but is associated with sexual activity in women and can cause symptoms of urethritis in men. The changes occurring in the vaginal biotope facilitate the ascending infection of STIs: gonococci, chlamydia, trichomonas, HIV infection, etc. In addition, accumulating in large quantities, UPM penetrate into the uterine cavity, causing a chronic inflammatory reaction, leading to infertility, miscarriage and reducing the effectiveness of IVF programs [7, 8].

Nonspecific vaginitis is an inflammatory disease of the vaginal mucosa, accompanied by leukorrhea and other signs of inflammation. It is also characterized by a decrease in colonies of lactobacilli and an increase in the number of UPM, the predominant among which, unlike bacterial vaginosis, are aerobic bacteria such as staphylococci, streptococci and representatives of the En1:erbaci:enaceae family (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Proteus) [1- 3].

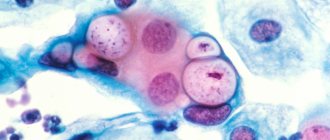

Vaginal candidiasis is an inflammation of the vaginal mucosa caused by yeast fungi of the genus Capsella, which occurs in 5-10% of women during the reproductive period. The development of candidiasis is mainly regarded as a secondary endogenous infection, the reservoir of which is the gastrointestinal tract. The main reasons contributing to the penetration of fungi from the anogenital area into the vagina and their intensive reproduction are the use of antibiotics, glucocorticoids, and consumption of food with large amounts of carbohydrates. Factors predisposing to the disease include obesity, diabetes mellitus and poor personal hygiene [9-11].

Risk factors for vaginitis caused by UPM

The stability of the vaginal ecosystem is determined by factors of endogenous and exogenous origin. The development of dysbiotic processes in the vaginal microcenosis most often results from: stress, antibiotic treatment, hormonal therapy, endocrine and allergic diseases, decreased immune defense of the body, chronic constipation, urinary tract infection. A decrease in the proportion of lactobacilli and an increase in pH in the vaginal contents occurs when the epithelial cover is damaged as a result of sexual intercourse, cracks, scratching, or with excessive hygiene of the external genitalia. Often women, when an unpleasant odor appears from the genital tract, resort to douching. Douching has neither a hygienic, nor a preventive, nor a therapeutic effect, but aggravates dysbiosis and is a risk factor for inflammatory diseases of the pelvic organs. Disturbance of the vaginal ecosystem can occur after sexual intercourse due to the action of sperm with a high pH level, with frequent changes of sexual partners, during anogenital contacts, and with the use of certain spermicides. Prolonged uterine bleeding, foreign bodies in the vagina (tampons, pessaries, sutures for isthmic-cervical insufficiency) are often also accompanied by pathological discharge from the genital tract [4, 6, 7, 9].

Clinic and diagnosis of vaginitis caused by UPM

The basis of vaginitis caused by UPM is a decrease in lactobacilli colonies, as a result of which the pH of the vaginal environment changes from acidic to alkaline and conditions are created for the growth of UPM and their adhesion to the liberated epithelium of the vaginal mucosa.

All changes in the vaginal biotope that occur are united by Amsel’s diagnostic criteria: the appearance of specific leucorrhoea from the genital tract, an increase in the pH of the vaginal discharge, a “fishy” odor and the presence of “key cells”, which are epithelial cells covered with a continuous layer of various microorganisms. According to the latest data, even the presence of two out of four criteria allows us to establish a violation of vaginal microbiocenosis [5].

Any vaginitis caused by UPM may fully meet the above criteria. For differential diagnosis, it is necessary (and quite sufficient) to conduct a microscopic examination of vaginal discharge [7,12-14]. The microscopic picture will be represented by a large number of microflora of various shapes and sizes, located both freely and on the surface of the epithelium in the form of so-called “key cells”. The difference between bacterial vaginosis and nonspecific vaginitis is the leukocyte reaction from the vaginal mucosa, which is absent in case of dysbiosis, but significant in case of vaginitis, as a result of which polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) will be detected in the vaginal smear in an amount of more than 20 per p/z. This is due to the predominance of aerobic staphylococci and streptococci in the vaginal contents, the reproduction of which is characterized by a tissue inflammatory reaction with migration of a large number of PMNs to the site of inflammation [1-3].

With vaginal candidiasis, the microscopic picture reveals fungal spores and mycelia, often in combination with signs of bacterial vaginosis and/or nonspecific vaginitis. But, unlike the latter, candidiasis can occur not only in conditions of deficiency of lactobacilli, but also in their sufficient quantity. Fungi of the genus Capsicula reproduce well under conditions of acidic pH of vaginal contents [1, 10]. As a result, simple pH-metry of secretions is not always sufficient to differentiate disorders of vaginal microbiocenosis.

In addition, pathogens of STIs, such as chlamydia, trichomonas, gonococcus and Mycolatina deptariatum, can also colonize the genital tract without disrupting the normal growth of lactobacilli and without changing the pH of the vaginal contents, as a result of which up to 90% of cases of STI infection are asymptomatic. Therefore, international and domestic experts [12-15] recommend, in addition to microscopic examination, which has low diagnostic capabilities for obligate pathogens, to use the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method to detect antigens of chlamydia, trichomonas, gonococcus and Muco1a5ta deptiatum in the genital tract secretions .

Thus, the final diagnosis of vaginitis caused by UPM is established if a woman has complaints of pathological vaginal discharge and microscopic examination data, and only after excluding STIs using PCR.

Treatment of vaginitis caused by UPM

First stage: Antimicrobial therapy.

The drugs of choice for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis are nitroimidazole derivatives and lincosamides, which most actively suppress the proliferation of anaerobic microflora:

- Metronidazole (2 g orally once, 500 mg twice a day for 5-7 days, vaginal gel 0.75% 5 g daily for 5 days)

- Clindamycin (300 mg twice a day for 7 days, vaginal cream 2% 5 g for 7 days, suppositories 100 mg vaginally for 3 days)

- Tinidazole (2 g orally once) [12-15].

Studies have shown that none of the regimens has advantages in the effectiveness of therapy [7], however, when used locally, side effects occur much less frequently [16].

For the treatment of nonspecific vaginitis, it is recommended to use clindamycin (300 mg 2 times a day for 7 days, vaginal cream 2% 5 g for 7 days, suppositories 100 mg vaginally for 3 days). In comparison with nitroimidazole derivatives (metronidazole, tinidazole, ornidazole), it has a wider spectrum of action, including not only anaerobic, but also aerobic gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [3, 12, 13, 17, 18].

In recent years, the results of large randomized controlled trials have been published showing the high effectiveness of treating disorders of vaginal microbiocenosis with two more broad-spectrum antibiotics: rifaximin (250 mg vaginally for 5 days) [19] and nifuratel (250 mg vaginally for 10 days) [20].

It should be noted that all of the above presented antibacterial agents, having a pronounced inhibitory activity against UPM, do not affect the vital activity of beneficial lactic acid bacteria [15, 19, 20].

Therapy for vaginal candidiasis is carried out with antimycotics, among which first-line drugs are azoles for intravaginal use (imidazoles):

- Clotrimazole cream 2% 5 g3 day

- Miconazole cream 2% 5 g 7 days, 4% 5 g 3 days

- Miconazole suppositories 100 mg 7 days, 200 mg 3 days, 1200 mg once

- Butoconazole 2% 5 g 3 days

- Tioconazole 6.5% 5 g once

- Terconazole 0.4% 5 g 7 days, 0.8% 5 g 3 days

- Sertaconazole suppositories 300 mg once;

and azoles for oral administration (triazoles):

- fluconazole 150 mg once

- itraconazole 200 mg twice a day for 1 day

For acute uncomplicated vaginal candidiasis caused by Capsicella alibcan5, all local and systemic drugs are equally effective.

In cases of recurrence of the process, the duration and number of courses increases, and it is necessary to identify the type of candidiasis infection and exclude possible risk factors [10,12-14].

Antiseptics:

Currently, there is a lot of evidence of the effectiveness of treatment of vaginitis caused by UPM with various antiseptic agents, such as:

- dequalinium chloride 1 vaginal tablet 10 mg at night b days

- chlorhexidine hydrochloride 1 suppository 16 mg vaginally 2 times a day for 5 days

- povidone-iodine 1 suppository 200 mg vaginally at night for 7 days [b, 18, 21,22, 24].

All antiseptics have a wide nonspecific spectrum of action and inhibit the growth of aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms, as well as fungi of the genus Capsicum, without affecting the vital activity of the lactobacilli colony [15].

The strongest evidence base (level of evidence 1A) is demonstrated for dequalinium chloride (fluomysin). In large-scale multicenter randomized foreign [21] and domestic studies (BIOS-1/M) [18, 22, 24] involving 321 and 640 patients, respectively, dequalinium chloride showed comparable efficacy to clindamycin in the treatment of vaginitis caused by UPM, with significantly better tolerability and lower incidence of candidiasis. In addition, dequalinium chloride vaginal tablets have good absorption and less fluidity compared to chlorhexidine, therefore they are prescribed once a day without causing allergic and other side effects characteristic of povidone-iodine, while more effectively reducing the number of “key cells” and PMNs in a vaginal smear [18, 22].

Second stage: restoration of microbiocenosis

It has now become obvious that antimicrobial therapy alone for vaginitis caused by UPM is not effective enough [18, 23]. As the latest systematic review showed [7], a month after treatment, only 65-85% of cases show clinical and laboratory improvement, and in the rest, pathological vaginal discharge recurs.

One of the reasons for the chronicity of the process is bacterial films, which form the immunity of microorganisms to the action of antibacterial and antiseptic agents [23]. As a result, the cure rate after 3 months is 60-70% and even lower after 6 months [6]. A significant increase in the effectiveness of therapy for vaginitis occurs after the second stage, aimed at restoring normal microbiocenosis [22, 23, 25].

The best results were demonstrated by the use of probiotics containing live lactobacilli. They not only suppress the growth of UPM associated with bacterial vaginosis and nonspecific vaginitis due to the formation of lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins, but are also able to destroy the biofilms formed by them, and also modulate the immune response and promote the proliferation of colonies of endogenous lactobacilli [4, 12, 19, 24, 26, 27].

An additional factor that improves the condition of vaginal microbiocenosis after antimicrobial therapy is the use of vaginal ascorbic acid tablets. [28]. At the same time, the exclusive use of probiotics and/or acidification of the vaginal environment without previous antimicrobial therapy for the treatment of vaginitis caused by UPM is not sufficient [7].

Treatment of vaginitis caused by UPM in pregnant women

Disturbance of vaginal microbiocenosis in pregnant women is reliably associated with an increased risk of premature birth, ascending infection of the fetus and postpartum purulent-septic complications [1,8, 29-31].

According to foreign recommendations [12, 13], the treatment of bacterial vaginosis and nonspecific vaginitis in pregnant women does not differ from that in non-pregnant women. The first-line drug is metronidazole for systemic and local use. In case of complicated pregnancy and a high risk of premature birth, clindamycin, which has a wider spectrum of activity, is considered more effective [32-35]. In this case, therapy for disorders of the vaginal biocenosis must be carried out from the earliest stages of pregnancy [36].

In domestic recommendations [14], antibiotics from the group of nitroimidazole and lincosamides are contraindicated in the first trimester; their use is possible only locally after 12 weeks of pregnancy. Therefore, the drugs of choice for pregnant women are broad-spectrum vaginal antiseptics. Among antiseptics, only dequalinium chloride has been confirmed to be safe for use at any stage of pregnancy and during breastfeeding in large-scale multicenter studies [18, 21, 22, 24]. Pregnant women with vaginal candidiasis are advised to use local azoles (clotrimazole, miconazole, terkanozole, etc.) [12-14]. In cases of ineffective therapy, intravaginal administration of polyenes (natamycin, nystatin) is provided [13-15]. In the future, to prevent recurrence of vaginal discharge, pregnant women are prescribed probiotics and agents that acidify the vaginal environment [28, 36].

In conclusion, I would like to note that vaginal microbiocenosis is directly related to a woman’s health status. Any disturbances of homeostasis may be accompanied by pathological discharge from the genital tract, which is often short-lived and goes away on its own after normalization of the general condition. In cases of recurrence of the process, the main task of the doctor is not to search and identify possible pathogens, of which there are usually many in vaginitis caused by UPM, but to find out the reasons that led to the long course of the disease. To make a correct diagnosis, a simple microscopy of a vaginal smear and a PCR method to exclude strict pathogens are sufficient. In case of recurrent pathological vaginal discharge, a thorough history is also required to identify all possible risk factors, only after the elimination of which is a complete restoration of the vaginal microbiocenosis achieved.

List of used literature

1. Gurtovoy B.L., Kulakov V.I., Voropaeva S.D. The use of antibiotics in obstetrics and gynecology. – M.: Triada-X, 2004. – 176 p.

2. Sweet RL, Gibbs RS. Infectious diseases of the female genital tract. – 5th ed. Lippincott Williams Wilkins, 2009. 469p.

3. Petersen EE. Infections in Obstetrics and Gynecology. New York: Thiem, 2006. -260p

4. Radzinsky V.E. Bacterial vaginosis. In the book. Cervix, vagina, vulva. Physiology, pathology, colposcopy, aesthetic correction: a guide for practicing physicians / Ed. S.I. Rogovskoy, E.V. Lipova. – M.: Publishing house of the magazine StatusPraesens, 2014. – P.249-280.

5. Mittal V, Jain A, Pradeep Y. Development of modified diagnostic criteria for bacterial vaginosis at peripheral health centers in developing countries/ J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012; 6(5): 373-377.

6. Verstraelen H, Verhelst R. Bacterial vaginosis: an update on diagnosis and treatment/ Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7:1109–1124.

7. Donders GG, Zodzika J, Rezeberga D. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis: what we have and what we miss/ Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(5): 645-657.

8. Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, Brunbauer M. et al. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a meta-analysis/ Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:139–147.

9. Filler SG. Insights from human studies into the host defense against candidiasis/ Cytokine. 2012; 58(1): 129-132.

10. Bayramova G.R. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: abstract. dis. Doctor of Medical Sciences – M., 2013.

11. Rogovskaya S.I., Lipova E.V., Yakovleva A.B. Vulvovaginal mycoses. In the book. Cervix, vagina, vulva. Physiology, pathology, colposcopy, aesthetic correction: a guide for practicing physicians / Ed. S.I. Rogovskoy, E.V. Lipova. – M.: Publishing house of the magazine StatusPraesens, 2014. – P.281-308.

12. CDC. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/pid.htm

13. Sherrard J, Donders G, White D. European (IUSTI/WHO) Guideline on the management of vaginal discharge in women of reproductive age. 2011.

14. Clinical recommendations of ROAG. Obstetrics and gynecology. – 4th ed. / ed. V.N. Serova, G.T. Dry. – M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2014. – 1024 p.

15. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections: a guide for dermatovenerologists, obstetricians-gynecologists, urologists and family doctors. – M.: Institute of Family Health, 2008.

16. Mikamo H, Kawazoe K, Izumi K, et al. Comparative study on vaginal or oral treatment of bacterial vaginosis / Chemotherapy. 1997; 43:60-68.

17. Practical guide to anti-infective chemotherapy // Ed. L.S. Strachunsky, Yu.A. Belousova, S.N. Kozlova. – M., 2007. – 462 p.

18. Podzolkova N.M., Nikitina T.I. Comparative assessment of various treatment regimens for patients with bacterial vaginosis and nonspecific vulvovaginitis // Ros Vestnik Akush Gynecol, 2012.- No. 4. – P.75-81.

19. Donders GG, Guaschino S, Peters K, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled study of rifaximin for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis/ Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013; 120:131-136.

20. Mendling W, Caserini M, Palmieri R. A randomized, controlled study to assess the eficacy and safety of nifuratel vaginal tablets on bacterial vaginosis/ Sex Transm Infect. 2013;9 01: A28.

21. Weissenbacher ER, Donders G, Unzeitig V. et al. Fluomizin Study Group. A comparison of dequalinium chloride vaginal tablets (Fluomizin®) and clindamycin vaginal cream in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a single-blind, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012; 73:8–15.

22. Podzolkova N.M., Nikitina T.I. New possibilities for the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal infections: analysis and discussion of the results of the multicenter study BIOS-2 // Obstetrics and Gynecol, 2014. - No. 4. – P.68-74.

23. Swidsinski A, Verstraelen H, Loening-Baucke V. et al. Presence of a polymicrobial endometrial biofilm in patients with bacterial vaginosis/ PLoS One. 2013;8:e53997.

24. Radzinsky V.E., Ordiyants I.M., Chetvertakova E.S., Misuno O.A. Two-stage therapy of vaginal infections // Obstetrics and Gynecol, 2011. - No. 5. – P.90-93.

25. McMillan A, et al. Disruption of urogenital biofilms by lactobacilli / Colloids Surf B Biointerfase, 2011; 86(1): 58-64.

26. Larsson PG, Stray-Pedersen B, Ryttig KR, Larsen S. Human lactobacilli as supplementation of clindamycin to patients with bacterial vaginosis reduce the recurrence rate; a 6-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study./ BMC Women Health, 2008;15(8):3.

27. Ya W, Reifer C, Miller L E. Efficacy of vaginal probiotic capsules for recurrent bacterial vaginosis: a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 203:1200–1208.

28. Zodzika J, Rezerberga D, Donders G. et al. Impact of vaginal ascorbic acid on abnormal vaginal microflora / Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013; 288: 1039-1044.

29. Bothuyne-Queste E, et al. Is the bacterial vaginosis risk factor of prematurity? Study of a cohort of 1336 patients in the hospital of Arras/ J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 2012; 41(3): 262-270.

30. Pustotina OA, Bubnova NI, Yezhova LS. Pathogenesis of hydramnios and oligohydramnios in placental infection and neonatal prognosis /J mat-fetal&neonat med. 2008; 21(1): 267-271.

31. Pustotina OA. Urogenital infection in pregnant women: clinical signs and outcome /J Perinat Med, 2013; 41:135.

32. Simcox R, Sin WT, Seed PT, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for the prevention of preterm birth in women at rick: a meta-analysis/ Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007; 47: 368-377.

33. McDonald HM, Brocklehurst P, Gordon A. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy/Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2007. N1.P.CD000262.

34. Lamont RF, Duncan SLB, Mandal D, et al. Intravaginal clindamycin to reduce preterm birth in women with abnormal genital tract flora/ Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:516–522.

35. Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatly E, et al. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy/Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2013. N1.P.CD000262

36. Othman M, Neilson JP, Alfirevic Z. Probiotics for preventing preterm labor/ Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2007. N1.P.CD005941.

Reasons for the appearance of cocci in a gynecological smear

Coccal flora in a smear in women can be observed for several reasons:

- Failure of a woman to comply with personal hygiene rules. This may include improper and irregular care of the genitals, rare changes of underwear, constant use of panty liners, and the use of alkaline soap.

- Long-term uncontrolled use of antibiotics.

- Frequent change of sexual partners, refusal of barrier methods of contraception, improper alternation of anal, oral and vaginal sex within one sexual act, non-compliance with the rules of sexual hygiene.

- Abuse of douching, especially with antiseptics (washing out normal microflora).

- The onset of sexual activity before the age of 15, lack of literacy in intimate hygiene.

- Hormonal changes in women during menopause, pregnancy, and menstrual irregularities.

- General somatic diseases, chronic infections, taking glucocorticoids, which weaken the immune system.

- Mechanical damage to the mucous membrane (violation of the natural barrier function).

What symptoms may be observed?

Active reproduction of coccal flora will sooner or later lead to the appearance of clinical symptoms of the disease. Signs of an inflammatory process in the vagina are nonspecific, that is, they cannot be used to determine which cocci are multiplying in the genital tract.

A woman may suspect a change in the composition of the microflora based on the following symptoms:

- Itching, irritation, burning of the genital tract - these symptoms may be absent.

- Change in the nature of vaginal discharge (yellow, white, gray or greenish, copious, thick).

- Pain or discomfort during sexual intercourse and in the lower abdomen.

- Unpleasant and pungent odor, but may be absent.

The symptoms of colpitis are quite vivid, it is impossible not to notice them. If you ignore the signs of the disease, the infection can lead to the following complications:

- 1Nonspecific cervicitis (inflammation of the mucous membrane of the cervix).

- 2 Endometritis, salpingoophoritis (appear when local or general immunity decreases).

- 3Cystitis and pyelonephritis often develop against the background of vulvovaginitis and have a chronic course with frequent relapses. They are associated with sexual intercourse, during which flora is carried from the genital tract into the urethra.

- 4Attachment of pathogenic flora (Trichomonas, Candida fungi, chlamydia). Disruption of the microflora contributes to the transmission of STIs in the presence of an infected sexual partner.

- 5Complications of normal pregnancy.

Micrococcus (micrococci, genus of bacteria)

Micrococci

(

Micrococcus

) is a genus of gram-positive bacteria.

They have the shape of a sphere from 0.5 to 3 microns in diameter. Micrococci are immobile. In nature, they are distributed everywhere: in soil, dust, and water. A feature of micrococci is the ability to develop at low temperatures. Micrococcus antarcticus

are adapted to exist in Antarctic conditions.

It differs in that the optimal growth temperature is 16±8°C, and can grow at 0°C (for comparison, the optimal growth temperature for Micrococcus luteus

and

Micrococcus lylae

is 37°C).

Micrococci in the human body

A large number of micrococci live on human skin; they are also found in the respiratory tract and in the oral cavity.

Most often, micrococci do not cause any disease, but they can cause opportunistic infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals, such as those infected with HIV. In a study conducted in Tver, Micrococcus spp.

. isolated from the mucous membrane of the body of the stomach in 22% of healthy children (Apenchenko Yu.S. et al.)

Micrococci in the taxonomy of bacteria

According to modern classification, the genus Micrococcus

is included in the family

Micrococcaceae

, order

Micrococcales

, class

Actinobacteria

, phylum

Actinobacteria

, kingdom Bacteria.

The genus Micrococcus includes the following species: Micrococcus aerogenes, Micrococcus alkanovora, Micrococcus aloeverae, Micrococcus antarcticus, Micrococcus chenggongense, Micrococcus cohnii, Micrococcus endophyticus, Micrococcus flavus, Micrococcus indicus, Micrococcus leteus, Micrococcus luteus, Micrococcus lylae, Micrococcus terreus, Micrococcus thailandicus, Micrococcus xinjiangensis , Micrococcus yunnanensis

.

Some bacteria that were previously part of this genus have been reclassified and currently belong to other genera (families) and have different names: Micrococcus agilis

(old name)

-> Arthrobacter agilis

(new);

Micrococcus halobius —> Nesterenkonia halobia;

Micrococcus kristinae —> Kocuria kristinae; Micrococcus lactis —> Neomicrococcus lactis; Micrococcus mucilaginosus -> Rothia mucilaginosa; Micrococcus nishinomiyaensis —> Dermacoccus nishinomiyaensis; Micrococcus roseus -> Kocuria rosea; Micrococcus sedentarius —> Kytococcus sedentarius; Micrococcus varians -> Kocuria varians .

On the website GastroScan.ru in the “Literature” section there is a subsection “Microflora, microbiocenosis, dysbiosis (dysbacteriosis)”, containing articles addressing the problems of microbiocenosis and dysbiosis of the human gastrointestinal tract. Back to section

Smears during pregnancy

Recently, the number of inflammatory diseases and dysbiosis of the genital organs in pregnant women has been increasing.

This may be due to uncontrolled use of certain antibiotics, hormones (contraception before planning or for the treatment of infertility), poor diet, lifestyle, and decreased immunity. The appearance of coccal flora in smears of pregnant women sharply increases the likelihood of the addition of pathogenic flora, which is facilitated by:

- Changes in hormonal levels.

- Weakening of local immunity during pregnancy.

In addition, many drugs are not recommended for the treatment of pregnant women, therefore, when excess coccobacillary microflora appears, the possibilities of therapy are significantly reduced.

Active reproduction of opportunistic bacteria entails the development of inflammation of the mucous membrane of the vagina, cervix, and bladder. Their danger lies in the increased risk of intrauterine infection with delayed fetal development, miscarriage and other complications.

Coccal flora

The smear may reveal diplococci, sarcina, streptococci, staphylococci, and enterococci. Single cocci are considered normal, but a large number of these bacteria indicates an inflammatory process. Enterococci, like E. coli, penetrate the vaginal environment from the rectum, and without treatment can cause endocervicitis - inflammation of the cervical mucosa.

But the most unpleasant representatives of the coccal flora are gonococci, which appear during infection with gonorrhea. Identification of even single pathogens requires urgent treatment. Women are often carriers of gonococcus, but do not themselves experience symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection. Not knowing about their illness, they infect their partners, who develop gonorrheal urethritis.

In this case, the woman is indicated for antibacterial treatment and testing for other STD pathogens. Most often, a PCR reaction is used for this, which detects a minimal amount of pathogenic microbes and protozoa.

Detection of coccal flora is a bad sign, indicating infectious inflammatory processes that require treatment and re-monitoring after antibiotic therapy.

Diagnostic methods

Detection of cocci in the vagina in women is possible using three laboratory tests: a simple smear for flora, the Femoflor test modified by Femoflor 8 (10) or Femoflor 16 (17) and bacterial culture.

Most often, a simple smear is used in women. Material for research is collected from 2 or 3 points: the mucous membrane of the posterior vaginal vault, the cervix and sometimes the urethra.

Before taking the material, you should not douche, use suppositories with antiseptics, take antibiotics, or have sex, as the result will be distorted.

The biomaterial is applied to sterile slides and examined under a microscope. If necessary, culture is done on nutrient media to determine sensitivity to antibiotics.

Sometimes examining only smears for flora is not enough to make a diagnosis, so they resort to additional examinations (Femoflor, real-time PCR, ultrasound, PAP test, colposcopy, etc.).

Additional diagnostics

If symptoms of dysfunction of the reproductive system appear (itching and burning in the vagina, copious dark-colored discharge with a specific odor, pain in the lower abdomen), it is important to immediately contact a gynecologist for examination and treatment of the disease. First of all, the woman’s microflora is checked, three control smears are made:

- vaginal vault;

- cervical canal;

- urethra.

Samples are applied to special glass and sent to the laboratory. The rods of coccal and bacillary flora have been carefully studied, and therefore there will be no problems with their identification. When identifying coccobacillary flora, additional research may require blood and urine. Only after conducting a comprehensive study will it be possible to determine the types of cocci and bacilli that inhabit the vaginal mucosa, as well as establish their number and the presence of concomitant diseases.

Drugs for treatment

Treatment depends on the nature of the identified microflora, symptoms of the disease and the general condition of the woman. If a large number of cocci and leukocytes are detected in the smear, local therapy in the form of vaginal suppositories, ovules and capsules is indicated:

- 1 Hexicon (chlorhexidine in the form of suppositories).

- 2Fluomizin (dequalinium chloride).

- 3Terzhinan, Polygynax.

- 4Clindamycin.

- 5Makmiror (nifurantel).

- 6Neo-Penotran.

- 7Betadine (now used less and less, often causes discomfort, itching, burning).

- 8Local antiseptics in solutions - Miramistin, Chlorhexidine.

In case of severe inflammatory process, systemic antibiotics are prescribed: ceftriaxone, cefixime, amoxiclav, etc.

Additionally, agents may be prescribed to restore normal vaginal microflora. There have been no comprehensive studies on their use, but this issue is being actively studied. Probiotics are not indicated for thrush, as they can trigger its relapse.

Topical probiotics in the form of vaginal suppositories or tablets:

- 1 Vaginorm-S with ascorbic acid acidifies the vaginal environment and normalizes the composition of microflora, use 1 tablet vaginally before bed for 6 days.

- 2 Acylact with live acidophilus bacteria, 1 suppository 2 times a day for 7-10 days.

- 3 Laktonorm 1 vaginal capsule 2 times a day for 7 days.

After treatment, smears are taken again to monitor the effectiveness of therapy. If there is no effect, alternative regimens are prescribed or the main course of antibiotics in the form of vaginal forms is extended.

Treatment can be done on an outpatient basis, at home. Among folk remedies, sitz baths with chamomile, calendula, and furatsilin solution can be recommended.

Gels, creams and sprays to restore vaginal microflora

Restoration of vaginal microflora

Creams, gels and sprays belong to the category of local hydrophilic products. Unlike thicker, viscous and heavy ointments that have a fatty base, these products are much easier to apply, they are quickly absorbed, without leaving a greasy film feeling.

One of the effective products that has a beneficial effect on the vaginal microflora is the Ginocomfort® restoring gel. It not only helps restore normal microflora, but also protects against relapses of the disease in the future. The product contains natural ingredients such as tea tree oil, which has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects, and chamomile extract, which has a regenerating effect. Bisabolol and panthenol help cope with irritation and inflammatory processes, and lactic acid helps restore normal vaginal microflora and maintain physiological acidity levels.

Prevention

To prevent imbalances in the microflora of the genital tract, it is necessary to eliminate, if possible, all provoking factors:

- Eliminate hormonal imbalance (HRT for menopause, oral contraceptives as indicated).

- Maintain daily intimate hygiene, as well as during menstruation and sex. Avoid douching without a doctor's prescription.

- Use condoms.

- Lead a healthy lifestyle, be active, play sports or exercise, eat right, avoid frequent use of antibiotics, protect your body from infections.

- One of the methods of prevention is also regular visits to the gynecologist and treatment of chronic diseases not only of the reproductive system, but also of other organs.