On November 8, 1895, Wilhelm Roentgen (Professor at the University of Würzburg, Germany) discovered the effects of radiation that would later be named after him.

The source of the X-rays turned out to be a Crookes tube that was turned on due to carelessness and was located 1.5 meters from the jar of salt. The photo shows one of the first x-rays of the hand of the scientist’s wife.

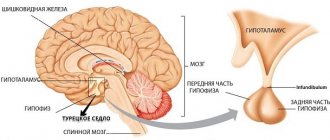

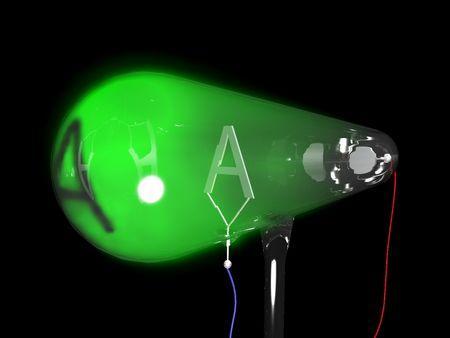

Roentgen studied and formulated the basic properties of the radiation he found and created the first X-ray installation from a Crookes tube and a high voltage source (Ruhmkorff coil). The resulting image was recorded on a photographic plate.

Revolution in medicine

X-ray diagnostics instantly becomes indispensable (the method is still one of the most used, fast and inexpensive types of diagnostics).

Already at the beginning of the twentieth century, mobile devices were added to stationary X-ray installations, which were mainly used for the needs of the army. For example, one of the first devices in the Russian Empire was installed on the notorious cruiser Aurora. The presence of mobile X-ray units has greatly simplified the work of military field surgeons.

You can undergo a digital X-ray examination in Kherson at the diagnostic department of the Persha Private Polyclinic MC.

The Mystery of Professor Roentgen

One of the oldest Soviet radiologists, editor of the “Radiation Diagnostics” section of the Great Medical Encyclopedia, Associate Professor L. M. Freidin, based on many years of studying the life and work of V. K. Roentgen, expresses his point of view on the history of his great discovery.

Many great discoveries and inventions are accompanied by legends. Archimedes jumped out of the bath naked and shouted “Eureka!” running through the streets, formulating his law... Newton, who lay down to rest in the garden from scientific work and received an apple on the forehead... Mendeleev, who saw his periodic table in a dream... Robert Koch, a modest health doctor who discovered Vibrio cholera only because his loving wife gave it to him a cheap microscope for your birthday...

A similar legend describing the discovery of X-rays goes like this. On Friday evening, November 8, 1895, in the German city of Würzburg, a little-known professor, Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen, was experimenting with cathode tubes. According to one version, when leaving the office, he forgot to turn off the Ruhmkorff coil and, turning around, saw a luminous object on the table, which forced him to return and find out what was the matter. According to another, more common version, he, working in the evening in the dark, discovered that a sheet of cardboard with a layer of platinum-barium cyanide that happened to be on the table began to glow every time the tube was turned on. This surprised and interested him so much that he... At this point the “pure legend” ends and an explanation of real facts begins based on it. Struck by an unprecedented phenomenon, always calm and balanced, he suddenly locks himself in his office and, although his apartment is only one floor above, the fifty-year-old professor begins to do incredible things. X-ray orders his wife not to disturb him, only to bring food at a certain hour, sets up a camp bed in the laboratory and locks himself from the inside for seven whole weeks.

He comes out only on the fiftieth day, having during this time discovered the mysterious X-rays, writing a message “On a new kind of rays,” which creates a world sensation and makes the author world-famous.

The message consists of seventeen theses that explain everything. It is clear that a completely new type of radiation has been discovered, penetrating through objects opaque to visible light and possessing a number of other remarkable properties. Now it is clear why photographic plates glowed near the cathode tubes, why phosphors glow—in addition to the cathode tubes, invisible X-rays are also emitted.

In a matter of days, the abstracts were duplicated and sent by Roentgen to the world's leading physicists in order to “stake out” the discovery. Soon Roentgen gave his first and, perhaps, only report on the rays he found at the Würzburg Society of Naturalists and Physicians. The presiding well-known anatomist Kölliker calls the discovery “stunning” and proposes to henceforth call X-rays X-rays.

A modest, uncommunicative, “buttoned up” professor from provincial Würzburg within a few days became a world-famous object of interest not only for scientists, but also for the general public.

So, in the fall of 1888, forty-three-year-old Professor Roentgen received the keys to the apartment and to the physics laboratory, located in the same building. He lives quietly and modestly, avoiding close contacts with Würzburg professors, avoids participating in meetings of various scientific societies and only once a year allows himself the luxury of spending a vacation in Switzerland, visiting his favorite places from his youth, skiing in the Alps, and sledding. , hunt and take a break from your duties.

In 1894, Roentgen had to endure a great loss - at the age of fifty-five, Kundt died, who recognized and developed in him the abilities of an experimental physicist, who knew and appreciated his integrity, hard work, extraordinary conscientiousness and forgave the other side of this - slowness and, if you like, slow-wittedness ... You can’t do anything, you can’t remove the words from the song.

This was the case in 1879, when Roentgen was still working as a professor in Giessen. The Berlin Academy announced a competition with a large cash prize for anyone who can establish a connection “between electrodynamic forces and the dielectric polarization of electrodes.” The topic was formulated in a very complex and unclear manner, and therefore none of the physicists were able to solve it by the appointed time. Nine years passed before Roentgen, through a series of very subtle and ingenious experiments, established that a dielectric moving in a uniform and constant magnetic field excites an electric current, that is, in essence, Roentgen solved the problem posed by the Berlin Academy. He did not consider it possible to submit his work to the competition until he had thoroughly checked it and was firmly convinced of the absolute reliability of the results obtained. When he finally published his work in 1888, it turned out that all deadlines for receiving the prize had long passed. The bonus, which he could have received if he had not been so conscientiously slow, literally slipped out of his hands. And Frau Bertha was also very upset.

Roentgen, of course, could not help but realize that the reason for the loss of the award was his excessive thoroughness and slowness. The fact that the phenomenon he discovered was given the name “Roentgen current”, if it served as a consolation, was very weak. Indeed, now only specialists know about the Roentgen current.

Having later become the director of the Physics Institute in Würzburg, Roentgen, a very modest and self-critical man, certainly understood that, in essence, he had not accomplished anything particularly significant in physics. True, in a narrow circle of physicists, by that time he had gained a reputation as an outstanding experimenter. But the professor is already fifty years old, and behind him there is nothing but the “Roentgen current.” Not enough.

The discovery of X-rays has been in the air for a long time. It is now reliably known that many physicists who worked with cathode rays, long before Roentgen, already held X-ray photographs in their hands, but were unable to “see” them, that is, to understand their origin.

His finest hour will not take place. Therefore, the only path to success for him is complete renunciation of everything, nothing but work, until complete victory is achieved... or until a message arrives that he has been ahead of him.

Why didn't you tell your wife? What if it doesn’t work out... Why look defeated in the eyes of your only loved one.

With assistants it's a different matter. Roentgen understood perfectly well that as soon as the scientific world learned of his discovery, many scientists would clutch their heads: “Where were we looking! Yes, that was clear!” I understood that there would be many who would challenge his priority. This is exactly what happened later. That's why he removed his assistants, not wanting to have either co-authors of the discovery or witnesses to failure, if one happened.

As for the subsequent heated debates about priority, which involved scientists from many countries, including Russia, Roentgen never took part in them, either verbally or in writing. Roentgen resolutely refused any patent rights and privileges to the X-ray tube, which he invented to replace the cathode one. He categorically rejected the very lucrative material offers of German and American firms, declaring that his discovery should belong to all humanity, and he did not need any personal benefits. There is every reason to believe that the nature of the rays he discovered was not clear to him. No wonder he himself called them X-rays until the end of his days. After all, X-ray radiation is formed in a vacuum tube when cathode rays are decelerated by an obstacle located in their path. And cathode rays are not rays at all, as Roentgen and other physicists of his time believed, but a stream of electrons, as we now know, but Roentgen not only did not know electrons at that time, but also for many years after their discovery, when they were for most physicists were reality, did not recognize their existence. He did not even allow this term to be uttered at his institute, and only when Roentgen’s closest student, later the founder of the Soviet physics school, A.F. Ioffe, did work under his leadership that would have been simply impossible without the recognition of the existence of electrons, did he give up.

I think this should be given to Roentgen not as a reproach, but as a praise. He never spoke or wrote about what he did not know. But he had enough integrity and courage to admit his mistakes. When Roentgen was convinced that electrons did exist, he, wanting to atone for his mistake, invited the famous Lorentz, the author of the electron theory, to the post of professor of physics at the institute. And when Lorentz could not accept the offer, he secured the approval of theoretical physicist Sommerfeld, one of the authors of quantum theory, in this position. In any case, he did everything possible to ensure that the Physics Institute he led did not lag behind in theoretical issues.

In an article on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of X-rays, A. F. Ioffe characterizes his teacher as follows: “Among physicists involved in the study of natural phenomena, there are two directions: some strive for generalizations and consider facts as a way to verify or refute their ideas; others - mostly experimental observers - are more interested in the phenomena themselves and the processes that determine them. Crookes, Hertz and other researchers who studied cathode rays were interested in ideas about their electrical nature, about matter, etc. They approached the observed phenomena with a certain prejudice: they were interested in phenomena that could serve as a means of confirming those ideas held by they have already been formed.

Roentgen approached every phenomenon he studied objectively; he was interested in its impeccable description, and then explained it in one way or another. But I did not attach decisive importance to this explanation either.”

This can be seen, in particular, from his famous theses. While we are talking about forfeits, everything is extremely clear and concise. But then an attempt begins to explain the essence of X-rays and a timidity unusual for Roentgen appears - where did the previous confident intonations go? “Can’t new rays be attributed to longitudinal vibrations of the ether?” he timidly asks himself and, as if justifying himself, adds: “I must admit that during my research I was imbued with this idea and allow myself to make this assumption, although I am very well aware that it needs further evidence."

In these erroneous words, we think we should see not derogation; and the greatness of Roentgen’s personality. For who could have known then that twenty years later quantum mechanics would appear, reconciling polar points of view and convincingly revealing not only the essence of X-rays, but their dual nature—both as wave oscillations and as energy quanta. Major discoveries lead to others. In the “radiation fever” that followed the X-rays, Becquerel’s rays were discovered, and pure radium was obtained by Pierre and Marie Curie.

Later, the “finest hour” struck Roentgen a second time. But this time he did not hear their fight.

He had every opportunity to discover X-ray diffraction and invent X-ray diffraction analysis. When he irradiated the crystals with X-rays, it was enough to place them at some distance from the photographic plate, and not close, as he did, and then... There were half a step before the discovery, but they remained untaken. True, the power of his tube was too small.

Max Laus, the 1914 Nobel laureate in physics who discovered X-ray diffraction, later said: “It is often asked why this man, after his remarkable discovery, so stubbornly refrained from further publication. Many motives have been put forward to explain this fact, and some of them were not very flattering for Roentgen. I consider all these motives to be false. In my opinion, the impression of this discovery was so strong that he could never free himself from it.”

Roentgen became the first ever Nobel Prize winner in 1901.

His worldwide fame was great, his recognition was undeniable. But at home, in Germany, his opponents did everything to ensure that his name was quickly forgotten. Kaiser Wilhelm II could not forgive the fact that when Their Majesty deigned to visit the museum headed by Roentgen and make some thoughtful remark, the scientist spoke in the sense that from the point of view of physics this was not entirely correct. Roentgen's funeral in the family crypt in Giessen, where he bequeathed to be laid next to Frau Bertha, was more than modest, only close relatives were present. No one even thought of objecting to the burning of the rich archive of the great scientist.

With the Nazis coming to power, the name of Roentgen was completely crossed out from the list of the best scientists in Germany, and the word “X-ray” was prohibited in technical and medical literature. No, from the point of view of fascist racial theories, it was impossible to find fault with Roentgen. The point is different—F. Lenard, the founder of “Aryan physics”, Hitler’s court physicist, credited himself with the discovery of Roentgen. But who remembers Lenard today?

The name and work of Roentgen live on in hundreds of thousands of X-ray medical offices around the world, in hundreds of thousands of X-ray flaw detection installations in industry, in that, despite all the progress of technology, the X-ray tube has remained practically the same as the quiet Würzburg professor made it almost ninety years ago.

How X-ray machines have changed

Initially, it took several hours to create an x-ray, and everyone received a significant dose of radiation - patients, nurses, laboratory assistants, doctors. To speed up the process, special intensifying screens began to be used, film was improved, and other innovations gradually improved the quality of images.

Until the 20s of the twentieth century, the so-called gas (ion) tubes, over time they were replaced by vacuum electron tubes. Once the negative effects of ionizing radiation were identified, efforts were made to reduce the harmful effects of X-ray radiation on patients and staff.

CT or X-ray: the doctor explained that it is not recommended if COVID is suspected

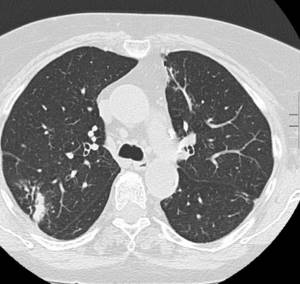

Diagnosing COVID-19 is not easy - its symptoms are similar to those of other diseases, but chest x-rays and computed tomography of the lungs come to the aid of specialists. Both diagnostic methods can detect signs of lung damage from COVID-19. Computed tomography allows you to display the organ from different angles, while x-rays allow you to view the organ in one projection.

A chest x-ray (x-ray) is the most commonly performed test for patients with serious respiratory complaints. What starts out as bronchitis may turn out to be pneumonia. The image allows the doctor to see the shadows.

The tricky thing about COVID-19 is that in the early stages of the disease, a chest x-ray may show completely normal lungs. And in patients with severe disease, the picture on the pictures may resemble pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome.

“Standard radiography has low sensitivity in detecting initial changes in the first days of COVID-19 disease and cannot be used for early diagnosis,” emphasizes. O. Head of the X-ray department of the State Budgetary Healthcare Institution “Clinical Hospital No. 6 named after. G. A. Zakharyin" Alexey Shalashov. — A chest CT scan is a specialized test that uses X-rays to create three-dimensional images of the chest. CT scans can detect characteristic changes in the lungs of patients with COVID-19 even before positive laboratory tests for infection appear.

The information content of radiography increases with increasing duration of pneumonia. Its advantage compared to CT is its high throughput. In addition, radiography using mobile (ward) devices is the main method of radiological diagnosis of pathology of the chest organs in intensive care units,” the doctor said.

On X-rays of the lungs of people with coronavirus infection, doctors see “bilateral multifocal consolidations.” Such a complex name suggests that the infection progresses, grows and covers the lungs almost entirely. The term “compaction” refers to the filling of the air space of the lungs with fluid or other products of inflammation - mucus and blood. The phrase "bilateral multifocal" means that the abnormalities occur in both lungs in different places.

CT images of patients show both multifocal opacities and a “ground glass effect.” That is, sections that should be completely visible in a healthy person are shown as if through frosted glass. This is due to the filling of the lung air space with fluid, collapse (the lungs seem to “deflate”), or both.

CT detects lung changes in a significant number of patients with asymptomatic and mild forms of the disease that do not require hospitalization. CT results in these cases do not affect treatment tactics and prognosis of the disease in the presence of laboratory confirmation of COVID-19. Therefore, the widespread use of CT for screening asymptomatic and mild forms of the disease is not recommended.

Referrals for X-rays and CT scans for patients with ARVI symptoms are issued only for specific medical reasons. Radiological data do not replace the results of testing for SARS-CoV-2. The absence of changes in CT does not exclude the presence of COVID-19 and the possibility of developing pneumonia after the study.

X-rays can be taken free of charge upon referral from a doctor in all city clinics and regional and inter-district centers of the Penza region.

Subscribe to PenzaInform in Google News and Yandex.News.

The most important news in the Penzainform telegram channel.

Without negativity and concisely. We are at Yandex.Zen.