Causes

Osteomyelitis develops when bacteria enter bone tissue, periosteum, or bone marrow. Bone infection can occur through the endogenous (internal) route, when bacteria enter the bone tissue through the bloodstream through the blood vessels. Such osteomyelitis is usually called hematogenous (translated from Greek - generated from blood). Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis is more common in infancy, childhood and adolescence; adults rarely suffer from it. Purulent inflammation of the bones can occur when microorganisms penetrate from the environment - this is exogenous osteomyelitis. An example of exogenous osteomyelitis is a bone infection that develops as a result of an open fracture, a gunshot wound, or after traumatic surgery (also called post-traumatic osteomyelitis). Another type of exogenous osteomyelitis is contact osteomyelitis, which occurs when purulent inflammation transfers to the bone from the surrounding soft tissues. The following conditions contribute to the development of osteomyelitis: alcohol abuse, smoking, use of intravenous drugs, vascular atherosclerosis, varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, frequent infections (3-4 times a year), impaired renal and liver function, malignant diseases (tumors) ), previous splenectomy (removal of the spleen), elderly and senile age, low body weight, poor nutrition.

X-ray technique

If osteomyelitis is suspected, it is necessary to select the optimal dose of X-ray radiation. The higher the hardness of the rays, the more contrast the image and the better the inflammatory areas are visible.

The chronic course of the pathology requires mandatory research. This is necessary to clarify the degree of damage and control the dynamics of the development of the process, since the study expands the field of view and helps the doctor fully imagine the volume of the lesion.

When sequestration and fistulas appear, the method of direct magnification of radiographs or fistulography is used - a study with intravenous contrast.

Diagnostics helps to accurately determine the extent of destructive damage to bone and soft tissue, and allows the traumatologist to select the optimal method of surgical intervention.

In the chronic course of hematogenous osteomyelitis, the technique is not very informative, since dense foci of sclerosis make visualization difficult. In this case, a fistula tomographic examination is required.

Symptoms

The clinical picture is usually characterized by a hyperacute onset of the disease with septic, toxic symptoms. The temperature is high; in older children, osteomyelitis begins with chills; the pulse is rapid, the child is very lethargic and gives the impression of being seriously ill. In the first days, local symptoms of osteomyelitis are sometimes not expressed; a severe general condition completely determines the clinical picture. The patient usually complains of bone pain; the pain intensifies, the affected bone becomes sensitive to pressure. Local redness and swelling are not early symptoms of osteomyelitis, but after 2-3 days from the onset, when a subperiosteal abscess occurs, these signs are striking. When an abscess located under the periosteum breaks through, the pain decreases and redness, swelling, and fluctuation are detected.

What is it and how to treat it?

Osteomyelitis is an inflammation of the bone marrow with a tendency to progress.

This is what distinguishes it from the widespread dentoalveolar abscess, dry socket, and osteitis seen in infected fractures. Osteomyelitis affects adjacent cortical plates and often periosteal tissues. In the era of preantibiotics, osteomyelitis of the mandible was not uncommon. With the advent of antibiotics, the disease began to be detected less frequently. But in recent years, antimicrobial drugs have become less effective, and the disease has reappeared.

Diagnostics

During the examination, careful palpation (feeling with fingers) of the painful area is carried out, and the condition of the skin is noted (hot, there is redness and swelling, wave-like movements of the tissue are formed) and the general appearance of the damaged area (tight skin, “glossy” shine, swelling). Using gentle percussion (tapping), the source of infection is determined by increased pain in a specific area of swelling. In addition to assessing clinical manifestations and manual examination, laboratory research methods are used. A general blood test with a leukocyte formula in expanded form shows a shift to the left. This means that inflammation in the body is caused by bacteria. A general urine test shows the presence of inflammation and renal failure (in generalized forms of the disease) through the appearance of protein and an increase in certain indicators. A biochemical blood test shows the inflammatory process and notes renal and liver failure. At the same time, the parameters of bilirubin and protein change, the glucose level decreases, and the amount of some elements increases.

Along with laboratory methods, instrumental examination methods are used:

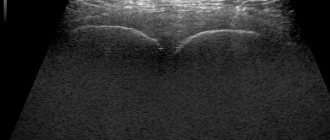

- Ultrasound is used to assess the size and shape of muscle lesions.

- Infrared scanning can show the presence of acute latent forms of osteomyelitis, identifying areas with increased temperature.

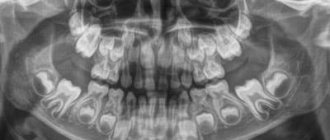

- Radiography is the most common method for diagnosing osteomyelitis. Using images, you can determine the localization of necrotic processes, the volume and severity of the infectious focus. X-rays can detect the disease in its early stages. As inflammation grows, the nature of the image on the images changes, so the time of the disease can be determined with high accuracy.

- Computed tomography is the most informative way to diagnose osteomyelitis in any of its manifestations. Using volumetric images, you can obtain not only data on the location and intensity of the infection, but also create a reconstruction of the surrounding muscle tissue and predict the course of the disease.

For an accurate diagnosis, which is of decisive importance in the treatment of osteomyelitis, a combination of laboratory and instrumental research methods is necessary.

After surgery

Regardless of the tactics used for joint replacement and the chosen model of the analogous joint, the quality and usefulness of postoperative restoration should now be in the first place. Here, much depends on the competence of specialists in matters of rehabilitation management of people who have undergone endoprosthetics after a permanent cure for osteomyelitis.

So, along with all rehabilitation measures for the normal resumption of motor and support functions of the limb and the prevention of all complications (pneumonia, thrombosis, thromboembolism, etc.), specialists carry out intensive antibiotic therapy. In this group of patients, it has a longer period of use - treatment lasts 2-6 months.

There is no uniform regimen of prolonged antibiotic treatment after surgery. In each individual case, doctors are guided by the general health status, data on the tolerability of dosage forms, sensitivity and the nature of clinical strains of purulent-septic pathogens.

The patient’s attitude towards his own rehabilitation no less influences the successful outcome of the operation and further quality of life. Therefore, do not be lazy, strictly follow all medical recommendations - from taking medications and wound care rules to the physical activity regimen prescribed to you.

Treatment

Treatment of acute osteomyelitis is carried out only in a hospital in the traumatology department. The limb is immobilized. Massive antibiotic therapy is carried out taking into account the sensitivity of microorganisms. To reduce intoxication, replenish blood volume and improve local blood circulation, plasma, hemodez, and 10% albumin solution are transfused. For sepsis, extracorporeal hemocorrection methods are used. A prerequisite for successful treatment of acute osteomyelitis is drainage of the purulent focus. In the early stages, burr holes are made in the bone, followed by washing with solutions of antibiotics and proteolytic enzymes. For purulent arthritis, repeated punctures of the joint are performed to remove pus and administer antibiotics; in some cases, arthrotomy is indicated. When the process spreads to soft tissues, the resulting ulcers are opened, followed by open rinsing. In the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis, surgery is indicated in the presence of osteomyelitic cavities and ulcers, purulent fistulas, sequestra, false joints, frequent relapses with intoxication, severe pain and dysfunction of the limb, malignancy, disruption of the activity of other organs and systems due to chronic purulent infection. A necrectomy is performed - removal of sequesters, granulations, osteomyelitic cavities along with the internal walls and excision of fistulas, followed by lavage drainage. After sanitation of the cavities, bone grafting is performed.

Treatment of chronic odontogenic osteomyelitis of the jaw

Treatment of chronic odontogenic osteomyelitis of the jaw is complex and includes surgical intervention and drug treatment.

I. During exacerbation of chronic osteomyelitis, the symptoms of acute inflammation are first relieved. If the causative tooth has not been removed previously, then it must be removed this time. Adjacent mobile teeth are trepanned and splinted, if not removed according to indications (after assessing their viability and x-ray examination). Sanitation of the oral cavity is mandatory and all chronic sources of infection are removed to prevent complications during subsequent procedures.

To facilitate the outflow of pus, fistulas or wounds are expanded, and primary surgical treatment of subosseous and perimandibular purulent foci is performed.

An important part of the surgical stage of treatment is sequestrectomy. After evaluating the radiograph, the formed sequesters are removed. Removal is performed through an intraoral or extraoral incision. Large sequestra in the area of the body and ramus of the lower jaw, as well as in the area of the infraorbital margin and zygomatic bone, are removed extraorally. Sometimes large necrotic areas of bone are broken into several parts for ease of removal. Incisions are made along the natural folds of the face for better aesthetics.

After removal of sequesters, attention is paid to granulations and sequestral capsule. Using a curettage spoon or even a milling cutter, pathological tissue is removed until the signs of healthy bone are revealed: alveolar bleeding, white bone, hard bone tissue.

The free space is filled with a biosynthetic osteotropic drug: kolapol, kolapan, etc. The wound is tightly sutured, drainage is left. The stitches are removed after 7-10 days.

II. Next, let's move on to drug treatment. As with other purulent diseases, etiotropic, pathogenetic and symptomatic treatment is carried out.

To eliminate the cause of the disease, the surgeon removes the causative teeth. But the infection remains in the blood, so the patient is prescribed antibacterial drugs: macrolides, cephalosporins. It is also worth prescribing the patient antifungal agents (Deflucan 150 mg once a week).

Since the patient’s immunity is reduced, it is recommended to prescribe immune drugs such as thymalin, T-activin, levomisol, staphylococcal toxoid.

In case of extensive damage to bone tissue, the patient is recommended to follow a gentle diet to prevent a pathological fracture of the jaw.

To reduce the symptoms of inflammation, detoxification and anti-inflammatory therapy is carried out. Physical therapy exercises and physiotherapy are individually selected for the patient to restore function.

Chronic osteomyelitis of the jaw. Outcomes and complications

Outcomes:

- Favorable - if the patient contacts a maxillofacial surgeon in a timely manner and receives adequate treatment, the patient’s full recovery is possible.

- Unfavorable – if treatment is insufficient and the patient contacts a doctor late, the following may occur:

- Exacerbation of the disease

- Jaw deformity,

- Jaw fracture - occurs due to minor physical impact, from which a healthy jaw would not be damaged,

- Complications of osteomyelitis: Abscesses and phlegmon of soft tissues of the face,

- Thrombosis of facial vessels and cavernous sinus,

- Mediastinitis,

- Death.

Introduction

Being a sign of an infectious process in bone tissue, pelvic osteomyelitis is characterized by a number of features that force us to classify such diseases into a separate group [2, 11]. A significant array of bones with a spongy structure, soft tissues, often difficult accessibility of foci, nearby internal organs, great vessels and nerve trunks [3, 12, 17] - all this together determines the difficulties in diagnosing and treating pelvic osteomyelitis. In most cases, pelvic osteomyelitis is much more severe than osteomyelitis of other localizations, since the spongy structure of the bones contributes to the rapid spread of the process [3, 5, 15, 21]. Osteomyelitis of the pelvis is characterized by purulent leaks and fistulas of complex shape and distribution, which can be located both inside and outside the pelvis [2, 6, 13, 20]. A significant number of observations of the chronic course of this disease are due to untimely diagnosis and late treatment [7, 8, 16]. With osteomyelitis of the pelvis, more often than with damage to bones of other localizations, we noted the development of sepsis, often with symptoms of multiple organ failure [3, 22]. Another feature of pelvic osteomyelitis is its polyfocal lesion, which further complicates the diagnosis and treatment of this category of patients [1, 3, 14, 18].

The polymorphism of the clinical manifestations of the disease, which largely depend on the localization and extent of the lesion, and the lack of information content of plain radiography often determine the delayed diagnosis [6, 19].

According to many authors, radical surgery is decisive in the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis, however, in the case of damage to the pelvic bones, palliative operations are often performed [4, 10]. This is due to the nature and characteristics of the pathological process in cancellous bone, difficulties of access to lesions, and the danger of damage to nearby important anatomical formations. The best results of treatment of pelvic osteomyelitis are observed in specialized institutions, the number of which clearly does not correspond to the prevalence of the disease [2, 9, 11].

Material and methods

The experience of our clinic is based on the results of examination and treatment of 223 patients with pelvic osteomyelitis of various origins and locations. Their ages ranged from 15 to 74 years, with the majority being of working age. There were 2.3 times more men than women. The duration of the disease ranged from 1 year to 42 years, in 3/4 of patients - from 5 to 25 years. Most often, osteomyelitis was of hematogenous origin - 159 (71.3%) patients. Traumatic osteomyelitis was less common in its three main forms: post-traumatic - in 9 (4.1%) patients, postoperative - in 23 (10.3%) and gunshot - in 3 (1.3%) patients. The remaining 29 (13%) patients had contact osteomyelitis, which developed in the presence of bedsores.

The most frequently noted lesions were the ilium and sacroiliac joint (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Frequency of damage to the pelvic bones by the osteomyelitic process. Less commonly, damage to the pubic and ischial bones occurred. A characteristic feature of pelvic osteomyelitis was multiple localization of the pathological process with simultaneous damage to several bones - 83 (37.2%) cases.

A picture of sepsis was observed in 54 (24.2%) patients with pelvic osteomyelitis, which once again emphasizes the severity of this disease.

Results and discussion

Pelvic osteomyelitis was often accompanied by the formation of purulent leaks in the soft tissues. Due to the complex anatomical structure of this area, knowledge of the main routes of infection has a significant impact on surgical treatment, including the choice of surgical approach. Conventionally, all variants of purulent leaks in pelvic osteomyelitis can be divided into intra- and extra-pelvic. Intrapelvic leaks were more common when the ilium and sacroiliac joint were affected. Often they spread along the iliopsoas muscle and vascular bundle, reaching the thigh. Extrapelvic leaks were usually located under the gluteal muscles. Often, leaks of pus burst open, forming fistulas with the most typical localization of the external opening in the gluteal, iliac, inguinal, and pubic regions. Often the external opening of the fistula was located far from the osteomyelitic focus, creating additional diagnostic difficulties.

From a practical point of view, it is important that any localization of purulent leakage in pelvic osteomyelitis is not strictly specific. The same location of the abscess may be a consequence of osteomyelitis of different localization. Along with this, intrapelvic abscesses create the danger of pus breaking into the bladder, rectum, and vagina with the formation of internal fistulas.

Diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis was based on clinical data and the results of instrumental research methods. The clinical picture of the disease, although not strictly specific, nevertheless depended on the course of the pathological process. In acute osteomyelitis, pain in the pelvic area of one location or another, often intense, functional impairment (especially with the formation of paraosseous ulcers), as well as manifestations of a systemic inflammatory reaction, came to the fore. A similar clinical picture was observed during exacerbation (relapse) of chronic osteomyelitis. However, in this case, the diagnosis of the disease was significantly simplified taking into account the existing medical history. The chronic course of pelvic osteomyelitis was accompanied by functioning purulent fistulas of various locations and, as a rule, an unexpressed clinical picture. Moreover, if in the case of acute osteomyelitis the clinical picture was largely determined by the origin of the pathological process (hematogenous, post-traumatic, postoperative osteomyelitis), then in the chronic course this difference was largely erased. The long course of pelvic osteomyelitis, repeated relapses of the disease, and repeated surgical interventions often led to pelvic deformation and gait disturbance.

Instrumental diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis was the most important part of the diagnostic search. The information content of various research methods depended on the duration of the disease and the characteristics of its course. In the early period of development of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis (up to 2 weeks), radioisotope research should be considered the most informative, which can provide a topical diagnosis of inflammation in bone tissue from the first day of the disease. It is also invaluable for diagnosing the polyfocal form of the lesion.

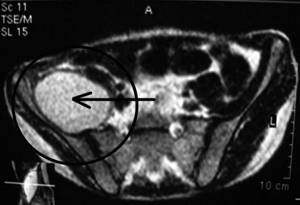

In contrast, the possibilities of plain radiography in acute hematogenous osteomyelitis are limited, since the development of structural changes in bone tissue requires considerable time (from several weeks to several months). In recent years, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been increasingly used to diagnose acute pelvic osteomyelitis. The capabilities of the method allow a detailed assessment of pathological changes in paraosseous soft tissues: infiltration, destruction, purulent leaks (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging for pelvic osteomyelitis. The intrapelvic abscess is indicated by an arrow. a - cross section.

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging for pelvic osteomyelitis. The intrapelvic abscess is indicated by an arrow. b — sagittal section. Additional methods for diagnosing acute pelvic osteomyelitis include ultrasound (ultrasound), which makes it possible to detect swelling and infiltrative changes in the muscles, as well as fluid accumulations, at an early stage of the disease.

Thus, in the diagnosis of acute pelvic osteomyelitis, among the instrumental research methods, osteoscintigraphy and MRI are the most informative.

In a chronic process accompanied by structural changes in the pelvic bones, X-ray methods come to the fore in diagnosis. The grossest changes can be detected by plain radiography: foci of destruction, periostitis, osteosclerosis, changes in the width of the pubic and iliosacral joints (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Plain X-ray of the pelvis of a patient with osteomyelitic lesions of the right iliac wing and sacroiliac joint. Paying tribute to the diagnostic capabilities of plain radiography of the pelvis in chronic osteomyelitis, it should be noted that sometimes they are insufficient. Among modern instrumental research methods, the “gold standard” for diagnosing chronic pelvic osteomyelitis is computed tomography (CT), which makes it possible to detail the nature of structural changes in bone tissue (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Computer tomograms of the pelvis of a patient with left-sided purulent sacroiliitis. a — cross-section: sequestration zone in the area of the sacroiliac joint.

Figure 4. Computer tomograms of the pelvis of a patient with left-sided purulent sacroiliitis. b — multiplanar reconstruction: destructive changes in the area of the sacroiliac joint are determined. To this day, conventional X-ray tomography has retained a certain significance in the diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis. However, we note that its capabilities are completely covered by modern CT.

Taking into account the fact that pelvic osteomyelitis is often accompanied by the formation of external purulent fistulas, fistulography plays an important role in diagnosis (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Fistulogram of a patient with pelvic osteomyelitis: multiple fistulous tracts and purulent leaks. The use of a water-soluble radiopaque substance allows one to obtain a complete picture characterizing the spread of fistulous tracts. The most informative is fistulography in combination with CT.

The infectious nature of the disease determined the high importance of microbiological research. The fact of identifying the causative agent of the pathological process was important in the context of antibacterial therapy. As studies have shown, the microbial landscape in pelvic osteomyelitis was characterized by extreme variability and depended on the origin of the disease, the presence of fistulas, paraosseous ulcers, and bedsores. In hematogenous osteomyelitis, both acute and chronic, the most common pathogen was Staphylococcus aureus, isolated mainly in monoculture. In post-traumatic and contact osteomyelitis, gram-negative microflora was more often isolated, often in associations. In a number of cases, these microorganisms were characterized by polyantibiotic resistance, which was partly evidence of the duration of the disease, superinfection, and ineffective treatment attempts at previous stages.

Treatment of patients with pelvic osteomyelitis included the use of a complex of measures, among which the surgical method played a primary role. The main indications for surgical treatment were determined by the presence of cavities of destruction in bone tissue, bone sequesters, paraosseous ulcers, purulent fistulas, ulcerative defects and bedsores, along with damage to the underlying bone, malignancy of tissue (usually fistulas) in the area of the osteomyelitic focus.

All operations were radical or palliative in nature. Radical operations included excision of fistulas, necrosequestrectomy to the extent of bone resection, sanitation and drainage of the bone cavity. In a number of observations (most often with contact osteomyelitis in patients with pressure ulcers), the most important component of surgical treatment was skin-plastic surgery, with the goal of closing the soft tissue defect over the bone with a full-thickness skin flap (fasciocutaneous or musculocutaneous).

The nature of osteonecrectomy was different and was determined by the prevalence and localization of the pathological process. More often it was resection of the wing, body of the ilium, pubic bones, pubic symphysis, acetabulum, sacroiliac joint.

Palliative operations - opening of paraosseous phlegmons, chronic ulcers, inadequately draining through the fistula, were performed as a stage of preparation for the upcoming radical operation, or as the only option for surgical treatment in the presence of contraindications to radical surgery. Surgical treatment was supplemented with antibacterial, detoxification, hemo- and immunocorrective (as indicated) therapy. The fundamental principle of antibacterial therapy for chronic pelvic osteomyelitis was the refusal to use antibiotics during the period of preparing the patient for surgery. The exceptions were patients with exacerbation of osteomyelitis, severe perifocal and general inflammatory reaction.

One of the most important issues in the surgical treatment of pelvic osteomyelitis is undoubtedly the choice of adequate surgical access. Its features for this localization of osteomyelitic lesion are often associated with the difficulty of access to the lesions, a large array of soft tissues located adjacent to the internal organs and important anatomical formations (vascular bundles, nerve trunks). Taking into account all of the above, it can be argued that surgical access to the lesion for pelvic osteomyelitis must meet a number of requirements, among which the most significant are the following: the possibility of adequate revision of the pathological lesion and performing radical osteonecrectomy, anatomicity, minimal trauma.

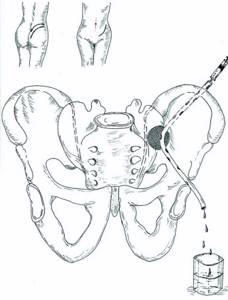

The clinic's original development is a surgical treatment option for purulent sacroiliitis. The peculiarity of this localization of pelvic osteomyelitis is that often purulent damage to the joint, which has a maximum thickness of several centimeters in the proximal parts, leads to the appearance of purulent fistulas and purulent cavities of both extra- and intrapelvic localization. Resection of the sacroiliac joint may be accompanied by the formation of a through defect, the drainage diagram of which is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6. Scheme of surgery for purulent sacroiliitis from a combined approach. The most rational in this case would be a combined approach: extrapelvic with dissection of the gluteal muscles (as close as possible to the place of their attachment to the pelvic bones), supplemented by intrapelvic extraperitoneal access to the joint with a skin incision along the edge of the crest of the iliac wing (an arcuate incision between the anterior and posterior upper awns). This access allows for adequate surgical treatment of the pathological focus and effective drainage of it using a flow-aspiration system.

A feature of the surgical treatment of contact osteomyelitis of the sacrum and ischium in patients with pressure ulcers is the need to replace the soft tissue defect over the affected bone. As a rule, long-term pressure ulcers of the IV degree (according to the classification of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1992) lead not only to the development of contact osteomyelitis of the underlying bone, but also to pronounced scar changes in the soft tissues, significantly reducing their reparative abilities. A prerequisite for a successful operation in this case will be: radical osteonecrectomy, excision of all scarred surrounding soft tissues, wound reconstruction with a displaced full-thickness skin flap. Taking into account the duration, traumatic nature of this surgical intervention, and significant intraoperative blood loss, we performed similar operations primarily on young and middle-aged patients with consequences of spinal trauma. In case of contact osteomyelitis of the sacrum or ischium (tubercle), osteonecrectomy was performed in a tangential manner, removing non-viable bone layer by layer. All scar tissue was carefully excised. Plastic surgery of a soft tissue defect in the sacral region was performed by rotating a gluteal fasciocutaneous flap formed next to the wound on a permanent feeding pedicle. The subflap space was drained using a tube brought out through the counter-aperture and connected to an active aspiration system.

In the treatment of osteomyelitis of the ischium against the background of bedsores, a soft tissue pillow over the ischial tuberosity was created in two main ways: 1) by moving the gluteus maximus muscle; 2) by moving m. gracilis. In the first case, the lower edge of the gluteus maximus muscle was mobilized, moved down and fixed to the periosteum in such a way as to cover the ischium. Method using m. gracilis involved isolating the muscle from a separate incision on the inner surface of the thigh, crossing it in the distal section, and mobilizing it. In a similar way, a muscle flap was formed on the proximal pedicle, which was rotated, passed through a tunnel under the fascia and fixed to the periosteum of the ischium, covering its tubercle. Due to the small loss of skin in this type of pressure ulcer, skin grafting was not used, and the edges of the wound were sutured without tension. A prerequisite for the subsequent rehabilitation of these patients was strict dosing of loads on the surgical area, preventing necrosis and ulceration of soft tissues and, as a consequence, relapse of osteomyelitis.

The immediate and long-term results of treatment for pelvic osteomyelitis were assessed up to 23 years after surgery. The main criterion for the effectiveness of the treatment was the elimination of the osteomyelitic process (stable remission). Good immediate results of treatment (up to 2 years) after surgery were noted in 86.3%, good long-term results (from 2 to 23 years) - in 72.4% of cases.

Thus, pelvic osteomyelitis is a complex and multifaceted surgical disease, including a whole group of diseases differing in pathogenesis. The difficulties of their diagnosis and treatment are associated primarily with the peculiarities of the anatomical structure of the pelvic bones and sometimes with difficulties in accessing osteomyelitic lesions. Only an integrated and differentiated approach to the problem of pelvic osteomyelitis will achieve positive treatment results for patients.